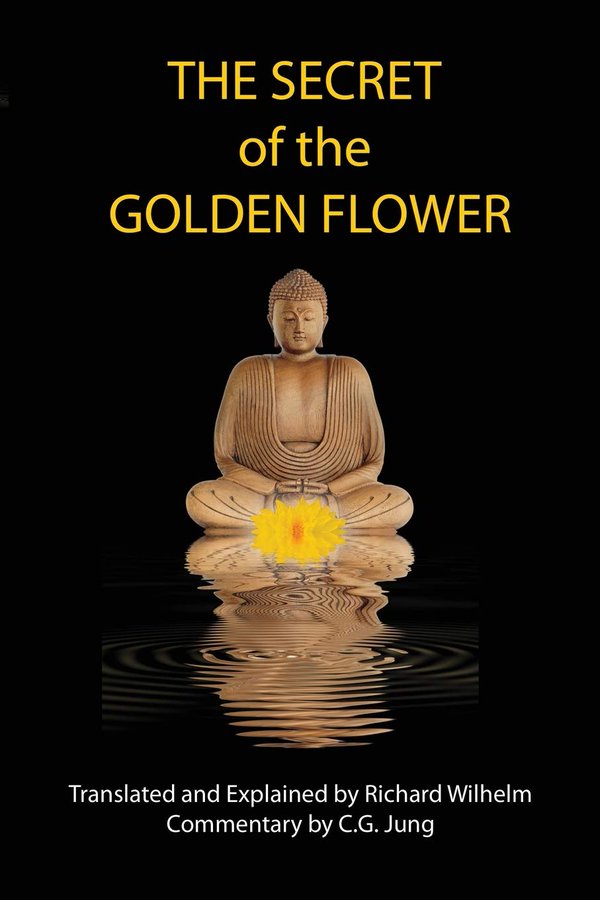

What fascinates me about Jung is his commitment to self-exploration and his use of analysis to discover his Self through the interpretation of dreams. He dedicated his life to this pursuit with genuine honesty and sincerity. Today, I present another section of The Red Book, Liber Novus, by Carl Jung, from Sonu Shamdasani’s Reader’s Edition.🙏

The following month, on a train journey to Schaffhausen, Jung experienced a waking vision of Europe being devastated by a catastrophic flood, which was repeated two weeks later, on the same journey. Commenting on this experience in 1925, he remarked: “I could be taken as Switzerland fenced in by mountains and the submergence of the world could be the debris of my former relationships.” This led him to the following diagnosis of his condition: “I thought to myself, ‘If this means anything, it means that I am hopelessly off.’ ” (Introduction to Jungian Psychology, pp. 47-48). After this experience, Jung feared that he would go mad.

(Barbara Hannah recalls that “Jung used to say in later years that his tormenting doubts as to his own sanity should have been allayed by the amount of success he was having at the same time in the outer world, especially in America” [C. G. Jung: His Life and Work. A Biographical Memoir/ New York: Perigree, 1976/, p. 109]. )

He recalled that he first thought that the images of the vision indicated a revolution, but as he could not imagine this, he concluded that he was “menaced with a psychosis.” (Memories, p. 200). After this, he had a similar vision:

In the following winter, I was standing at the window one night and looked North. I saw a blood-red glow, like the flicker of the sea seen from afar, stretched from East to West across the northern horizon. And at that time, someone asked me what I thought about global events in the near future. I said that I had no thoughts, but saw blood, rivers of blood (Draft, p. 8).

In the year directly preceding the outbreak of war, apocalyptic imagery was widespread in European arts and literature. For example, in 1912, Wassily Kandinsky wrote of a coming universal catastrophe.

From 1912 to 1914. Ludwig Meidner painted a series of works known as the Apocalyptic Landscapes, featuring scenes of destroyed cities, corpses, and turmoil (Gerda Bauer and Ines Wagemann, Ludwig Meidner: Zeichner, Maler, Literat 1884-1966 / Stuttgart: Verlag Gerd Hatje, 1991). Prophecy was in the air!

In 1899, the renowned American medium Leonora Piper predicted that in the coming century, a terrible war would erupt in various parts of the world, purging the world and revealing the truths of spiritualism. In 1918, Arthur Conan Doyle, the spiritualist and author of the Sherlock Holmes stories, viewed this as prophetic (A. C. Doyle, The New Revelation and the Vital Message / London: Psychic Press, 1918, p. 9).

In Jung’s account of the fantasy on the train in Liber Novus, the inner voice said that what the fantasy depicted would become completely real. Initially, he interpreted this subjectively and prospectively, that is, as depicting the imminent destruction of his world. His reaction to this experience was to undertake a psychological self-investigation. In this epoch, self-experimentation was used in medicine and psychology. Introspection had been one of the main tools of psychological research.

Jung came to realise that Transformations and Symbols of the Libido “could be taken as myself and that an analysis of it leads inevitably into an analysis of my own unconscious processes” (Introduction to Jungian Psychology, p. 28). He had projected his material onto that of Miss Frank Miller, whom he had never met. Up to this point, Jung had been an active thinker and had been averse to fantasy: “as a form of thinking I held it to be altogether impure, a sort of incestuous intercorse, thoroughly immoral from an intellectual viewpoint” (Ibid.). He now turned to analyse his fantasies, carefully noting everything. He had to overcome considerable resistance in doing this: “Permitting fantasy in myself had the same effect as would be produced on a man if he came into his workshop and found all the tools flying about doing things independently of his will” (Ibid.). In studying his fantasies, Jung realised that he was examining the myth-creating function of the mind (MP, p. 23).

Jung picked up the brown notebook, which he had set aside in 1902, and began writing in it (The subsequent notebooks are black, hence Jung referred to them as the Black Books). He noted his inner states in metaphors, such as being in a desert with an unbearably hot sun (that is, consciousness). In the 1925 seminar, he recalled that it occurred to him that he could write down his reflections in a sequence. He was “writing autobiographical material, but not as an autobiography” (Introduction to Jungian Psychology, p. 48).

From the time of the Platonic dialogues onward, the dialogical CE, St. Augustine wrote his Soliloquies, which presented an extended dialogue between himself and “Reason,” who instructed him. They commenced with the following lines:

When I had been pondering many different things to myself for a long time, and had for many days been seeking my own Self and what my own good was, and what evil was to be avoided, there suddenly spoke to me – what was it? I myself or someone else, inside or outside me? (This is the very thing I would love to know but don’t.) [St. Augustine, Soliloquies and Immorality of the Soul, ed. and tr. Gerald Watson (Warminster: Aris & Phillips, 1990), p. 23. Watson notes that Augustine “had been through a period of intense strain, close to nervous breakdown, and the Soliloquies are a form of therapy, an effort to cure himself by talking, or rather writing” /p. v/).]

While Jung was writing in Black Book 2:

I said to myself, “What is this I’m doing? This certainly is not science. What is it?” Then a voice said to me, “That is art!” This made the strangest sort of impression upon me, because it was not in any sense my impression that what I was writing was art. Then I came to this: “Perhaps my unconscious is forming a personality that is not I, but which is insisting on coming through to expression.” I don’t know why exactly, but I knew to a certainty that the voice that had said my writing was art had come from a woman … Well, I said very emphatically to this voice that what I was doing was not art, and I felt a great resistance grow up in me. No voice came through, however, and I kept on writing. This time, I caught her and said, “No, it is not”, and I felt as though an argument would ensue. {Ibid., p. 42. In Jung’s account, it appears that his dialogue took place in the autumn of 1913, although this is not certain, as the dialogue itself does not occur in the Black Book, and no other manuscript has yet come to light. If this dating is followed, and in the absence of the other material, it would appear that the material of the voice is referring to the November entries in Black Book 2, and not the subsequent text of Liber Novus or the paintings.}

To be continued!💖

The image on top: Pang Torsuwan -WHILE YOU WERE SLEEPING!

You must be logged in to post a comment.