Science Photo Library

It is inevitable to ignore the Myths of the feminine in ancient Egypt, especially this divine queen Ahmose Nefertari. I have already noticed that I shared several posts about this queen; however, she deserves another one, especially about this fantastic find of her statuette in such a beautiful form.

Ahmose-Nefertari was the first Great Royal Wife of the 18th Dynasty of Ancient Egypt. She was a daughter of Seqenenre Tao and Ahhotep I and a royal sister and wife to Ahmose I. Her son Amenhotep I became pharaoh, and she may have served as his regent when he was young. Ahmose-Nefertari was deified after her death. Wikipedia

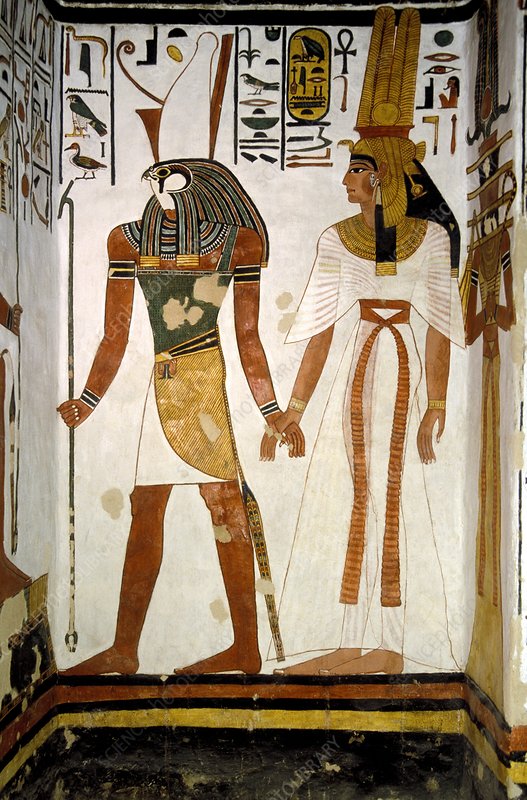

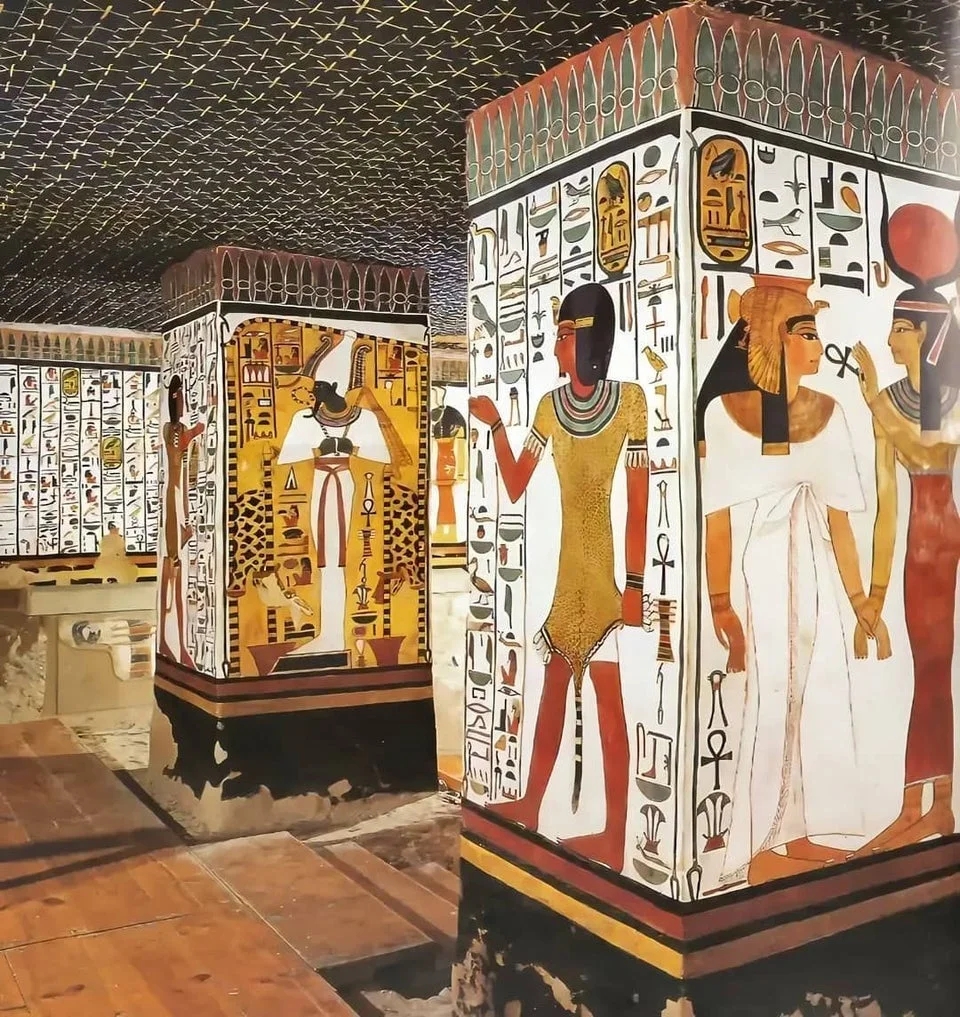

The 3,200-year-old tomb of Queen Nefertari. The paintings are considered the best-preserved and eloquent decorations of any Egyptian burial site.

Let’s read this brilliant explanation by Marie Grillot about this excellent artwork. via: égyptophile

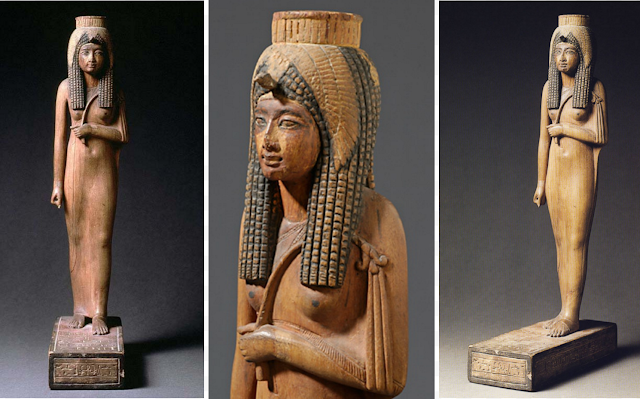

The great queen Ahmes (Ahmose) Nefertari at the Louvre

painted shea wood – Reign of Ramses II

Department of Egyptian Antiquities of the Louvre Museum (by acquisition in 1827 from the Drovetti collection – n°54) – N 470 – photos of the museum

According to some sources, this votive statuette of the great Queen Ahmes Nefertari entered the Louvre in 1827, along with the Drovetti collection, made up of 1970 pieces, which Champollion had urged the sovereign Charles X to acquire. Other writings indicate it as having arrived in the collections “before 1852” without further details.

Referenced N470, 35.5 cm high, it is made of shea wood and was carved in one piece” except for the left foot “. The queen is shown standing with her left leg forward. Her left arm is bent under the chest, and she holds a sceptre (fly swatter?) in her hand. Its flexible stem passes between her breasts, and flowers and straps bloom from the armpits to the beginning of the front -arms. Her right arm rests along the body, and her hand clutches an object that has now disappeared.

She is dressed in a long tight dress which covers her body down to her ankles, revealing her elegant forms, in particular a well-defined chest – the tip of the breasts of which is “haloed” with a circle of black paint -the navel with the bulge that surrounds it, as well as the bones of the knees.

The former deified queen Ahmes-Nefertari, protector of the workers of the royal tombs

painted shea wood – Reign of Ramses II – Department of Egyptian Antiquities of the Louvre Museum (by acquisition in 1827 from the Drovetti collection – n°54) – N 470 – photo from the museum

The face is beautiful, of an asserted nobility, with large almond-shaped eyes, an elegant nose and a sensual mouth.

If the statuette is offered to our eyes today in its soft blond wood, it was indeed polychrome, as evidenced by the touches of paint, red and black, which remain.

Ahmes Nefertari is the daughter of Ahhotep II and Seqénenré Taâ II. Great royal wife of Ahmose, mother Amenhotep I, she reigned for many years. She lived in Thebes and was buried in the necropolis of Dra Abu el-Neggah. The exact location of his tomb has been “several times questioned since Carter’s earlier excavations “.

Other statuettes, similar but of different sizes, are in various museums, such as Turin or Berlin.

Other statuettes, similar but of different sizes, are found in several museums, such as Turin or Berlin. Ahmes-Nefertari is the daughter of Ahhotep II and Séqénenré Taâ II. Great royal wife of Ahmose, mother Amenhotep I, she reigned for many years. She lived in Thebes and was buried in the necropolis of Dra Abu el-Neggah.

In his magnificent work “Les statues egyptiennes du Nouvel Empire au Louvre”, Christophe Barbotin describes precisely how the garment is made: “a tight-fitting fabric draped around the body tied under the right breast which leaves bare the right shoulder and covers the instep and the heel. The double fall of the fabric is marked by a braid starting behind the left shoulder and continuing behind the right shoulder (with a defective alignment from one shoulder to the other), constituting a diagonal on the bust on either side of the right breast. This braid is adorned with tight fringes on the left forearm and along the left leg to the heel. The covering of the drape is marked by an incised line connecting the knot under the right breast to the right ankle”.

Like the Valley of the Kings, this necropolis did not escape the looting that took place at the end of the Ramesside period. Around 1100 BC. AD (21st dynasty), the high priest Pinnedjem II, who then ruled the Theban region, did everything possible to preserve the royal remains. This is how he had them reinterred in his own tomb, dug in the rocky cirque of Deir el-Bahari, more precisely, in the rocks of Chaak el-Tablyah.

Coffin in sycamore wood of the great queen Ahmes-Nefertari, protectress of the workers of the royal tombs

discovered in 1871 – 1881 in the Cachette of the Royal Mummies (DB 320) at Deir el-Bahari

It was there, in the heart of the Theban mountains, that they rested until the summer of 1871, when the Abd el-Rassoul brothers, villagers from Gournah, discovered the tomb, its treasures piled up pell-mell, papyri, alabaster vases, shabtis and… forty-two mummies and sarcophagi.

They decided to seal this secret, to say nothing about it. “They went down three times in ten years to the bottom of their hiding place.” But years later, having noted the appearance of objects from clandestine excavations on the antiquities market, Gaston Maspero launched an investigation. After multiple and extraordinary developments, on July 5, 1881, in the presence of Mohamed Abd el-Rassoul in the crushing heat of Deir el-Bahari, Emile Brugsch, Ahmed Effendi Kamal, assistant to the Cairo museum, and Thadéos Matafian, supervised the “re-discovery” of this hiding place of royal mummies, now known as DB 320.

Among the mummies of the greatest sovereigns was that of the great queen Ahmes Nefertari. During the re-burial, she had been placed back in her 3.78 m sycamore wood coffin on which “she is majestically represented standing, arms crossed, covered with a mummy sheath and holding two ‘ankh’ signs in her hand. “.

The former deified queen Ahmes-Nefertari, protector of the workers of the royal tombs

painted shea wood – Reign of Ramses II

Department of Egyptian Antiquities of the Louvre Museum (by acquisition in 1827 from the Drovetti collection – n°54) – N 470 – photos of the museum

She wears an imposing three-part hairstyle, painted black, composed of plaits braided in a very particular way which fall to the upper part of the breasts. This wig is surmounted by the remains of a vulture (painted in yellow), the emblem of the goddess of Upper Egypt, Nekhbet, whose wings are worked on three levels and whose head adorns the middle of the forehead. The whole is surmounted by a mortar, part of which is missing.

The former deified queen Ahmes-Nefertari, protector of the workers of the royal tombs – painted shea wood – Reign of Ramses II – Department of Egyptian Antiquities of the Louvre Museum (by acquisition in 1827 from the Drovetti collection – n°54) – N 470

The face is beautiful, of an affirmed nobility, with large almond-shaped eyes, a long fine nose, and a sensual mouth. If the statuette is offered to our eyes today in its soft blond wood, it was indeed polychrome, as evidenced by the touches of paint, red and black, which remain. Thus: “according to the traces visible on the cheek of the lady, the flesh was painted in a dark colour, which is again a speciality of this deified queen”, specifies Christophe Barbotin.

The deified queen Ahmes-Nefertari – wood – New Kingdom

Turin Museum – cat 1369

She is “pegged” to an acacia wood base on which her name and titles appear: “The divine wife of Amon, the great royal wife, mistress of the double country, the beloved of her father Amon, the mother of the king, Ahmes Nefertari. May she live, be young and durable like Re, eternally”. It was dedicated by: “Djéhoutyhermaketef, who lived in Deir el-Medina and exercised the functions of quarryman during the reign of Ramses II (1279-1213 BC)”. The posthumous cult of Ahmes-Nefertari and Amenhotep I – very pronounced, especially within the community of workers of the royal tombs of Set Ma’at who made them their protectors – will continue for nearly five centuries after their “disappearance.”

The exact location of her grave was: “several times questioned since Carter’s old excavations”.

The former deified queen Ahmes-Nefertari, protector of the workers of the royal tombs – painted shea wood – Reign of Ramses II – Department of Egyptian Antiquities of the Louvre Museum (by acquisition in 1827 from the Drovetti collection – n°54) – N 470 – museum picture.

During the 21st Dynasty, the high priest Herihor who ruled the Theban region took care to restore the coffins and mummies of former rulers who had suffered from desecration or had been damaged by the robbers of graves. Their re-burial took place in the rocky cirque of Deir el-Bahari – more precisely in the rocks of Chaak el-Tablyah – in a tomb initially known to have been that of Princess Inhâpi.

This incredible “hiding place of royal mummies” was discovered in 1871 by Gournawis, the Abd el-Rassoul brothers. However, its “existence” will not be “officially” known to the Service des Antiquités until ten years later, in 1881.

Indeed, after an investigation with many twists and turns – prompted by the fact that artefacts arrived illegitimately and from unknown sources on the antique market – Gaston Maspero’s collaborators went back to the source of the traffic. This is how on July 5, 1881, in the crushing heat of the rocks of Deir el-Bahari, guided by Mohamed Abd el Rassoul, Emile Brugsch, Ahmed Kamal Effendi and Thadéos Matafian, supervised the “re-discovery” of this tomb – which will be referenced DB 320 -, which contained about fifty mummies – including about forty pharaohs.

The mummy of the great queen Ahmes-Nefertari had been replaced in her 3.78 m sycamore wood coffin (CG 61003) on which: “She is majestically represented standing, arms crossed, covered with a mummy sheath and holding hand two ‘ankh’ signs.

Sources:

“The Pharaoh’s Artists, Deir el-Medina and the Valley of the Kings“, Catalog of the exhibition at the Louvre Museum, April 15 – July 22, 2002, RMN

Ancient Egypt at the Louvre , Guillemette Andreux, Marie-Hélène Rutschowscaya, Christiane Ziegler, Hachette, 1997

Queens of the Nile, Christian Leblanc, Library of the Untraceable

“The wife of the god Ahmes Nefertary: documents on her life and her posthumous cult“, by Michel Gitton

http://www.louvre.fr/oeuvre-notices/la-reine-divinisee-ahmes-nefertari

Statue of Iahmes-Nefertari

http://cartelfr.louvre.fr/cartelfr/visite?srv=car_not_frame&idNotice=17793&langue=fr

New Kingdom Egyptian statues. 1, Royal and divine statues, Christophe Barbotin, Louvre Museum, 2007

The find of Deir-el-Bahari, Gaston Maspero, Émile Brugsch, 1881

General catalogue of Egyptian antiquities of the Cairo Museum N° 61001-61044, Coffins of the royal hiding places (1909), Daressy, Georges

https://archive.org/details/DaressyCercueils1909/page/n35

Maspero Gaston, The Royal Mummies of Deir el-Bahari

Maspero Gaston, Report on the find of Deir el-Bahari – Egyptian Institute – bulletin n° 2 – 1881

Pharaoh’s Artists, Deir el-Medina and the Valley of the Kings, Catalog of the exhibition at the Louvre Museum, April 15 – July 22, 2002, RMN

Ancient Egypt at the Louvre, Guillemette Andreux, Marie-Hélène Rutschowscaya, Christiane Ziegler, Hachette, 1997

Queens of the Nile, Christian Leblanc, Library of the Untraceable

https://books.google.fr/books?id=LgcKs7D2zYMC&pg=PA61&lpg=PA61&dq=N470+LOUVRE&source=bl&ots=8OuxeeKQwW&sig=zjntvF-hkHDx9TAgzyFbPwScmZY&hl=fr&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwj3lbebxujJAh=ILBos6KonefLYageqpagez&falqpagezADAf=ILBos6KonefLYAEQ

The wife of the god Ahmes Néfertary: documents on her life and her posthumous cult, Michel Gitton

Thank you so much Aladin for sharing another of Marie’s brilliant posts on Ancient Egypt. The photos and details here are just amazing, such fine detail!

Ever since I saw Egyptian hieroglyphics for the first time as a child (I was fortunate to see the Tutankhamun exhibition as a child) I’ve been fascinated and was delighted to learn through Ancestry DNA that my people were known as The Sea People, Mediterranean pirates no less!

Lol, it explains everything plus my interest in Egypt! Hope you had a lovely holiday and got to rest and catch up with your soul. Love and light, Deborah.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I think all of our cores are kind of going in (or coming from) that direction. 😅Apparently, you had an Egyptian lover in your family to get the chance for that visit.😉 Thank you, as always, for your kind words, dear friend.💖🙏

LikeLiked by 1 person

Fascinating. I quite enjoyed this slice of ancient history, Alaedin. I remember reading at least 1, maybe 2 other posts about her…. hmmm or were they about Nefertiti?

A lot of millenniums & much rich history.

Thank you!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Honestly, I myself am confused with so many posts which whom what!!😅 I just know I am getting older.😉 However, they are all beautiful and fascinating. Thank you, dear Resa.🙏💖🤗

LikeLiked by 1 person

🙏💖🤗

LikeLiked by 1 person

Again thanks for in-depth information descriptions and images of Egyptian history.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I am much obliged, and with my thanks for your appreciation. 🙏🤗

LikeLiked by 1 person