Hello friends!

I am back for a while from my holiday trip, although I am not fully recovered from a cold I caught a week ago, which I am still fighting to get rid of (it seems my immune system has been damaged after that problem earlier this year!). I didn’t plan to make a post today, but when I came across an article about the relationship between Poe and Melville, which I didn’t know about, I thought I would share it with you. Indeed, I should mention that I once published an article on Allan Poe; here it is!

As a new New Yorker, I once travelled across three boroughs to Woodlawn Cemetery to visit Herman Melville’s grave. I didn’t worship him as a hero but as a friend. Through the words of Professor Angela O’Donnell, who says that reading great writers is like having a conversation with them and fosters intimacy, I promised to visit often. Still, I was distracted by city life and never went back. However, a friend of another 19th-century American author never missed a visit.

The Baltimore Sun reports that, for decades, an anonymous “Poe Toaster” left three roses and a bottle of cognac at Edgar Allan Poe’s grave every January 19th. His mystery remains unsolved, as does Poe’s own death.

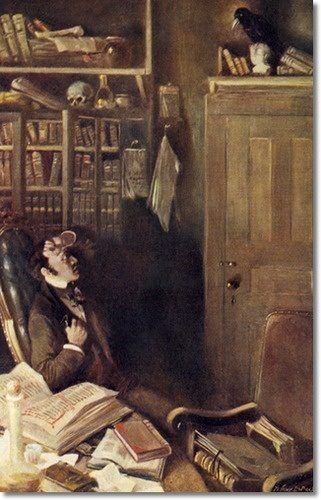

On October 7, 1849, the literary community remembered Edgar Allan Poe, a master of the macabre whose death remains shrouded in mystery. Although his anniversary has passed, his short, tragic life and death remain deeply saddening. He was found delirious on Baltimore’s streets, and the exact cause of his death remains unclear, speculated to be linked to alcoholism, rabies, or other health issues.

In the days leading up to his death, Poe grappled with personal turmoil and bouts of depression, reflecting the dark themes prevalent in his writing. His life mirrored the tragedies he explored—loss, madness, and mortality.

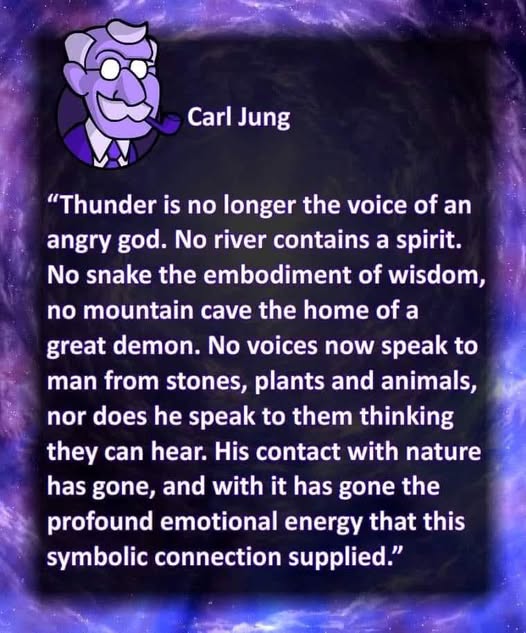

As we remember Poe, we not only honour his legacy as a pioneering voice in Gothic literature but also reflect on the profound connections between art and the struggles of existence, inviting us to confront the deeper aspects of the human condition he so eloquently captured.

The relationship between Edgar Allan Poe and Herman Melville is a compelling exploration of two iconic figures in American literature, whose works have shaped literary history. Both authors are monumental, yet their life paths and artistic styles diverged significantly, revealing profound themes of existentialism and the complexities of the human experience.

Edgar Allan Poe, born in 1809 in Boston, faced a tumultuous early life marked by personal tragedies. Orphaned as a child, he experienced the pain of loss that profoundly influenced his writing. His struggles with poverty and alcoholism fueled the dark themes in his work. Masterfully crafted tales such as “The Raven,” “The Tell-Tale Heart,” and “The Fall of the House of Usher” explore death, madness, and despair, establishing Poe as a master of horror and Gothic literature.

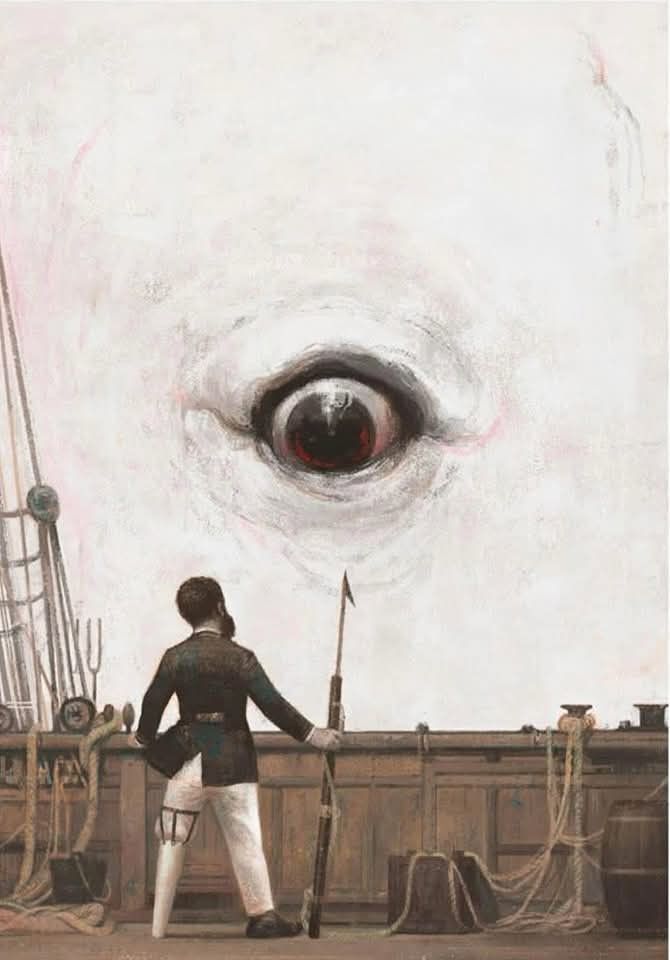

In contrast, Herman Melville, born in 1819 in New York City, enjoyed a more privileged upbringing that was disrupted by his father’s early death. This formative loss set him on a path of adventure at sea, which culminated in his magnum opus, “Moby-Dick.” Melville’s works engage with grand themes of nature and humanity, showcasing a narrative style that embodies the complexities of existence and human ambition.

Despite their differences, Melville and Poe respected each other’s literary talents. Poe’s sharp critiques of Melville’s early works, such as “Typee,” acknowledged Melville’s gift while highlighting differences in their narrative styles. Poe favoured compact storytelling, while Melville embraced sprawling narratives laden with existential questions.

Both writers engaged with themes of death and isolation, particularly evident in Melville’s Captain Ahab, who mirrors the psychological depths of Poe’s characters. Their respective narratives challenge audiences to confront profound aspects of the human condition. Timing also affected their careers; though Poe achieved fame earlier, Melville’s “Moby-Dick” was initially overlooked, though it would eventually be recognised as a key literary work.

Ultimately, the legacies of both authors flourished posthumously, with Poe celebrated for his innovative contributions to literature and Melville emerging as a foundational figure. This interplay between the two writers encourages contemporary readers to explore the connections that define their works.

In conclusion, the relationship between Poe and Melville offers a striking study of contrasting yet complementary voices in American literature. Their distinct views on existential despair and the human experience create a rich tapestry that continues to inspire and intrigue, leaving a lasting impact on generations of writers and readers alike.

Thanks, and have a good time, everybody.

You must be logged in to post a comment.