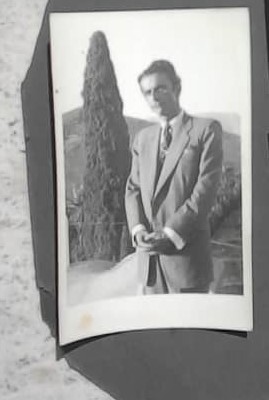

And yet, for the first time, I share an anniversary celebration of my father’s aniverssary. Of course, this Thursday is Good Friday, and in Germany, it is also recognised as Father’s Day. Therefore, I shall seize this opportunity to share something about him.

I must admit that I have few memories of my father’s life, as I was only seven when he passed away. However, some scenes remain in my mind—some joyful and a few burdensome. He was a dedicated writer who prioritised his work above all else, even above his love for family. I would say something between Charles Dickens and Dostoevsky!

Of course, I don’t want to say he didn’t love us. He was deeply in love with my mother and generally friendly toward his sons, although he was often preoccupied with work internally. Still, his books were the dearest things in his mind, and he enjoyed travelling extensively in Iran and Europe. Therefore, despite his fame and wealth, he was always broke! One of his colleagues at the newspaper where he worked told us that one day he came in and said he had sold his children! Of course, he meant he sold the rights to his best-selling books!!

I once lost his ID after I had it in my possession, and I don’t know where I left it. Therefore, I searched the Web and found something about him: he was famous then! Although I didn’t find his birthday, only his birth year, and he would be over a century old this year.

Here we go:

FAZEL, Javad (Moḥammad-Javād Fāżel Lārijāni; b. Lārijān, 1914; d. Tehran, August 19 1961), noted serial writer and a pioneering figure in simplifying and popularising religious texts. His father, Mirza Abu’l-Ḥasan Fāżel Lārijāni, was an eminent preacher in Āmol (q.v.), in northern Iran, and died when Javad was nine years old. Javad was brought up in a religious environment. His father introduced him to religious studies while attending Pahlavi Primary School in Āmol. In 1932, after finishing secondary education in Tehran, Fazel pursued religious studies at Islamic seminaries under Sheikh Moḥammad Aštiāni. He worked for the Ministry of Education in 1938, teaching literature and educational psychology at the Teachers’ Training School in Āmol for one year. Fazel graduated from Tehran University’s Faculty of Theology and Jurisprudence in 1945 and later became a translator at the Ministry of Agriculture until his death at 47 (M. Fāżel, p. 21). He also taught Persian literature in various secondary schools (M. Fāżel, p. 98).

In 1942, he joined Eṭṭelāʿāt-e Haftegi, a weekly journal of the oldest Tehran daily newspaper, Eṭṭelāʿāt, founded by ʿAbbās Masʿudi in 1923. He published most of his serialised stories there and also contributed to Badiʿ, a magazine established by Jamāl-al-Din Badiʿzāda in March 1943. That same year, Fazel became a member of the pro-German Paykār Party, founded by Ḵosrow Eqbāl, and wrote for its official publication, Nabard, edited by Jahāngir Tafażżoli. However, his affiliation with Paykār only lasted four months.

And here is something for my pride: Fazel’s straightforward literary style earned him a broad audience. His accessible translations of religious texts were utilised by politically active theologians and laypeople, such as Mortażā Moṭahari and ʿAli Šariʿati, who sought to engage Iranians with modern interpretations of Islamic teachings (Saʿid-Elāhi, p. 75). However, Fazel’s ‘free’ translations were criticised for lacking accuracy and fidelity to the original texts (Šahidi, p. 5).

Some are to be disappointed! But who cares? He wasn’t a devout Muslim, yet he believed in a mystical Islam. This perspective influenced his translations, incorporating his own thoughts and feelings.

With the advent of the Islamic Revolution in 1979, Fazel’s romantic stories were no longer in demand, but his religious texts gained vast popularity and were reprinted several times. Even his scattered articles were collected and published in quick succession, notable among them Zendegi-e por-mājarā-ye Moḵtār (Mokhtar’s adventurous life, 2000) and Qeṣaṣ-al anbiāʾ (Stories of the prophets, 2001).

Regrettably, my father has sold all or most of the rights to his best-selling books to publishers. Consequently, I have no claim to those rights.

In addition to religious texts, Fazel also translated several European novels into Persian, notable among them Ḵun o Šaraf (Blood and Honour, 1949), by Maurice Dekobra (1885-1973), Yek qalb-e āšofta (A Broken Heart, 1956), by Stefan Zweig (1881-1942), and Jāsusa (Spy, 1958) by Paul Bourget (1852-1935).

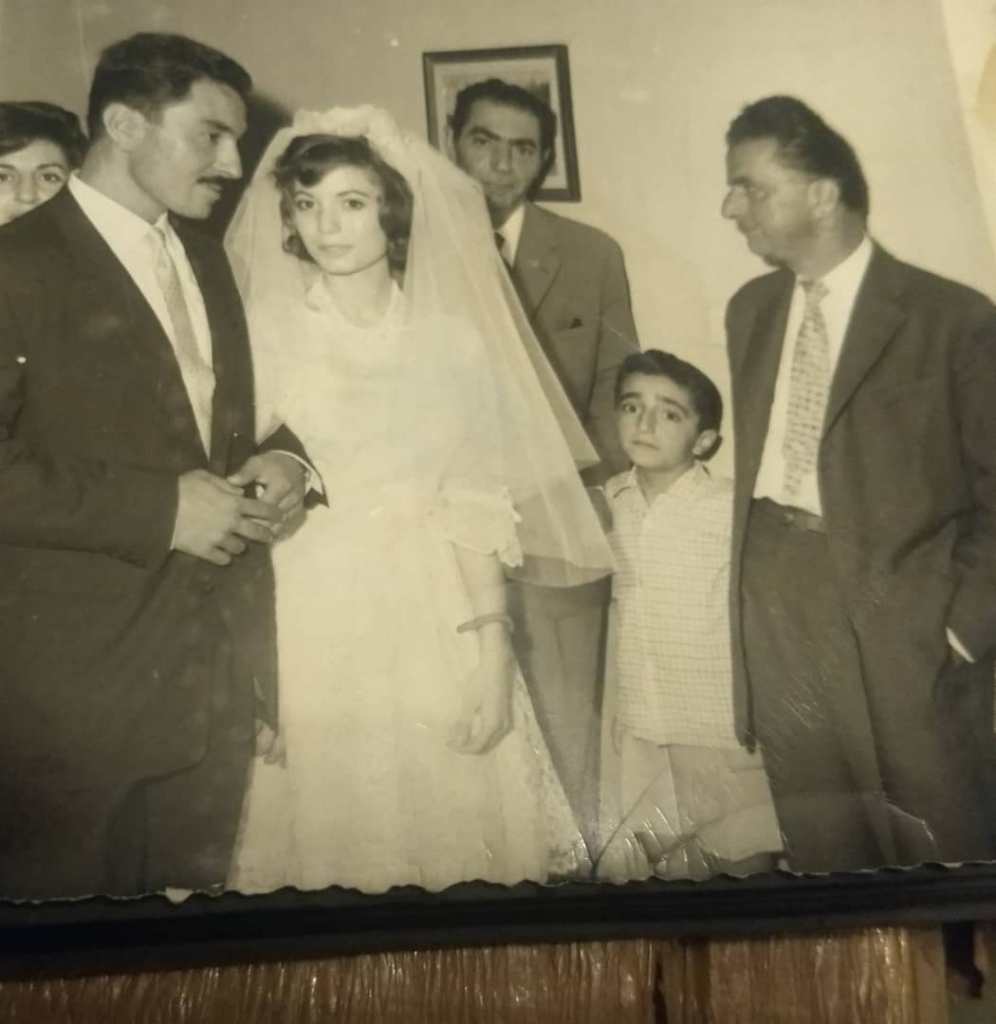

Fazel married in 1950. His wife, Mozayyan (Mosstofi) Fazel, depicted their life story together in Dāstān-e yek zendegi (A life story, 1964), which includes several of Fazel’s love letters to her. (And here is what I once wrote about their love story!). They had two sons: ʿAlaʾ-al-Din and Abu’l-Ḥasan. Javad Fazel died of cerebral thrombosis on August 19, 1961, and was buried in the Ebn Bābawayh (q.v.) cemetery near Tehran.

And yes, this passage is from the Encyclopaedia Iranica website, where you can read the full report. He passed away while Al and I were asleep. The next day, my mother made a mistake and lied to us, saying he had gone on a journey abroad. Alas, she ought to reveal the truth about his journey beyond the other side. It caused significant trauma for both of us in our lives of youth, but that is another story!

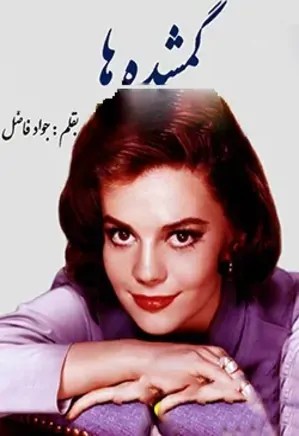

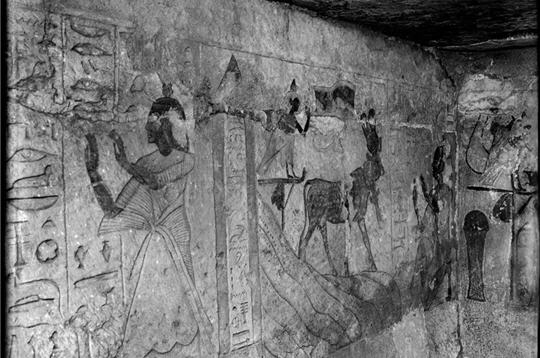

Here are some images of his Persian romans.

You must be logged in to post a comment.