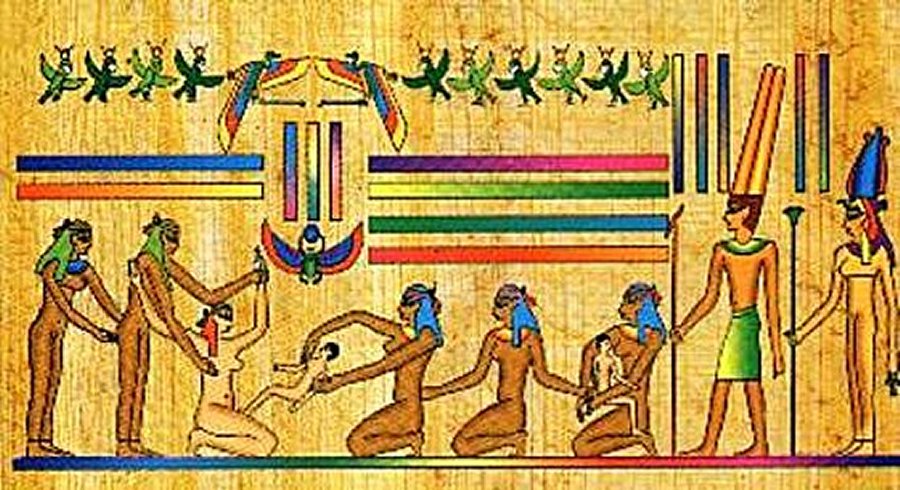

Of course, every holy book and religious ritual teaches that giving birth and having offspring is a highly important human act on this earth. No wonder, then, that it would go in the same way in ancient Egypt.

Most ancient Egyptian women laboured and delivered their babies on the cool roof of the house or in an arbour or confinement pavilion, a structure of papyrus-stalk columns decorated with vines.

In the Yogi method, the best way to bear a child is in the water! I believe if we let the newborn child into the water immediately, they would feel happy and free and could more easily grasp their changing world perception.

Photo by G. Blanchard (2006)

via Visualizing Birth

The standard childbirth practice in ancient Egypt has long been known from papyrus texts. It looked more natural as the woman delivered her baby while squatting on two large bricks, each colourfully decorated with scenes to invoke the magic of gods for the health and happiness of mother and child.

Let’s read this interesting report by the brilliant Marie Grillot about an enchanting find and the story of constant upspring in Old Egypt!

On this ostracon, a maternity scene more than 3000 years old…

via égyptophile

Department of Egyptian Antiquities of the Louvre Museum – E 25333 (previously at the Fouad I Agricultural Museum in Cairo

then in the collection of Moïse Lévy de Benzion, then in that of Robert Streitz, who donated it to the Parisian Museum in 1952)

photo © 2002 Louvre Museum / Georges Poncet

Several figured ostraca* from Deir el-Medineh illustrate this extraordinary, touching moment of motherhood, more precisely of the mother breastfeeding her newborn. The gesture, the tenderness, and the concentrated attention paid to the nurturing function remain immutable across the centuries.

This scene, dating from the 19th – 20th dynasty, is reproduced on a piece of limestone 15 cm high and 11.7 cm wide. The three characters are drawn in red ocher while their complexion is painted in yellow ocher and their hair in black.

It takes place in a beautiful plant setting, under a canopy, supported by columns (only one is visible on the right, the left part being lacunar), covered with lanceolate leaves of bindweed or convolvulus. “The leaves of bindweed have a symbolic meaning with a sexual connotation: they are often present in scenes relating to love and the renewal of life”, explains Anne-Mimault-Gout (“Les artistes de Pharaon”).

Department of Egyptian Antiquities of the Louvre Museum – E 25333 (previously at the Fouad I Agricultural Museum in Cairo

then in the collection of Moïse Lévy de Benzion, then in that of Robert Streitz, who donated it to the Parisian Museum in 1952)

photo © 2002 Louvre Museum / Georges Poncet

Emma Brunner-Traut calls this kiosk “the birthing arbour” and thinks “that it was a temporary building, raised in the open air for the moment of childbirth and that the mother remained there for 14 days until her purification”…

This birth pavilion sheltered the difficult hours of suffering inherent in childbirth, just as it witnessed the intense emotion linked to the miracle of giving life… Its aim was also, most certainly, to benefit the young, give birth calmly, rest and protect her, as well as the child, from potential external risks or dangers. In “Carnets de Pierre”, Anne-Mimault Gout evokes the interesting idea that: “These pavilions were perhaps the ancestors of the mammisis of the Greco-Roman temples, the birth chapels”.

Sitting on a curved stool equipped with a comfortable cushion, the mother is shown, turned to the right and naked, adorned only with a large necklace. Her body, leaning forward, seems to envelop and protect the infant she is breastfeeding. Unfortunately, the time has partly tarnished and erased its representation…

Department of Egyptian Antiquities of the Louvre Museum – E 25333 (previously at the Fouad I Agricultural Museum in Cairo

then in the collection of Moïse Lévy de Benzion, then in that of Robert Streitz, who donated it to the Parisian Museum in 1952)

photo © 2002 Louvre Museum / Georges Poncet

Her undone, untamed hairstyle —typical of that of women giving birth in ancient Egypt—attracts the eye. The hair raised in a totally anarchic manner on the head probably reflects the fact that during these extraordinary days, all the attention was focused on the child, to the detriment of the care given to his physical appearance…

As if to remind her that her new role as the mother should not make her forget her femininity, the young servant in front of her hands her a mirror and a kohol case. These toiletry accessories are, according to Anne Mimault-Gout, “charged with an erotic connotation linked, through beauty, to rebirth”. Young, his thin, slender body is naked. Her hair is tied in a ponytail on the top of her head, falling in a pretty curl over her shoulder. For J. Vandier d’Abbadie, “this hairstyle and the pronounced elongation of the profile evoke the iconography of Syro-Palestinian divinities – in particular, Anat and Astarte -, that is to say, that these young girls with high heads would be young asian maids”…

Department of Egyptian Antiquities of the Louvre Museum – E 25333 (previously at the Fouad I Agricultural Museum in Cairo,

then in the collection of Moïse Lévy de Benzion, then in that of Robert Streitz, who donated it to the Parisian Museum in 1952)

published here in Jeanne Vandier d’Abbadie “Deux ostraca figurés”, BIFAO, 1957 (p. 21-34, p. 22-23, fig. 2)

In her fascinating study “Postpartum purification and relief rites in ancient Egypt” (all of whose rich analyses, unfortunately, cannot be cited here), Marie-Lys Arnette returns to the rites represented on these figurative ostraca of the Ramesside period representing “gynoecium scenes”, as J. Vandier d’Abbadie calls them… “The actions that these scenes depict are indeed rites since they are very close formally to the representations of offerings made to the dead or the gods and follow the same codes: The beneficiary is seated while the officiant approaches them, standing and holding the objects they are about to offer in their hands. These scenes concern the period following birth, and the rites which appear there must allow the purification and aggregation of the mother. It is a question of representing the reliefs, the sequence we can attempt to restore – in a necessarily incomplete manner because the analysis depends on scant documentation”…

These representations are very precious because they are among the only ones that allow us to understand the intimacy of women… But what was their goal? E. Brunner-Traut, in particular, “suggests seeing ex-votos there. We can indeed consider these objects as having been used, in one way or another, in cults linked to fertility, but it is impossible to specify this use further”…

Department of Egyptian Antiquities of the Louvre Museum – E 25333 (previously at the Fouad I Agricultural Museum in Cairo,

then in the collection of Moïse Lévy de Benzion, then in that of Robert Streitz, who donated it to the Parisian Museum in 1952)

published here in Jacques Vandier d’Abbadie “Catalogue of figured ostraca of Deir el Médineh” II.2, n°2256-2722, IFAO, Cairo, 1937

This ostracon, which comes from Deir el-Medineh, is described by Jacques Vandier d’Abbadie in his “Catalogue of figured ostraca, 1937” under the number 2339. It is indicated as having previously been at the Fouad I Agricultural Museum in Cairo. It was then found in the collection of Moïse Lévy de Benzion, owner of a famous store in Cairo, who then offered it at auction under number 36 of his sale on March 14, 1947, in Zamalek. Robert Streitz, a Belgian architect based in Cairo, then purchased it. He kept it for several years before donating it in 1952 to the Department of Egyptian Antiquities of the Louvre Museum. It was registered there under the inventory number E 25333.

Marie Grillot

*Ostraca (singular: ostracon): Shards, silver or fragments of limestone, or even terracotta, which were, in antiquity, used by artisans to practice. This type of “support”, which they found in abundance on the sides of the mountain, allowed them to make and redo their drawings or writings until they reached excellence and were finally admitted to work “in situ” in the residences of ‘eternity.

They are generally classified into two categories: inscribed (hieroglyph, hieratic, demotic, etc.) or figured (drawing, sculpture).

Sources:

Figured ostracon – E 25333 https://collections.louvre.fr/ark:/53355/cl010004032 Jacques Vandier d’Abbadie, Catalog of figured ostraca of Deir el Médineh II.2, n°2256-2722, IFAO, Cairo, 1937 https://archive.org/details/DFIFAO2.2/page/n1/mode/2up Bernard Bruyère, Report on the excavations of Deir el Médineh (1934-1935). Third part. The village, public dumps, the rest station at the Valley of the Kings pass, Cairo, Printing office of the French Institute of Oriental Archeology (IFAO), (Excavations of the French Institute of Oriental Archeology = FIFAO; 16), p. 131-132, 1939 https://ia600606.us.archive.org/30/items/FIFAO16/FIFAO%2016%20Bruyère%2C%20Bernard%20-%20Le%20village%2C%20les%20discharges%20public%2C%20la%20station%20de %20rest%20du%20col%20de%20la%20valley%20des%20kings%20%281939%29%20LR.pdfEmma Brunner-Traut, Die altägyptischen Scherbenbilder (Bildostraka) der Deutschen Museen und Sammlungen, Franz Steiner, Wiesbaden, 1956 Jeanne Vandier d’Abbadie, Two figured ostraca, Bulletin of the French Institute of Oriental Archeology (BIFAO), 1957, p. 21-34, p. 22-23, fig. 2, IFAO, Cairo, 1957 https://archive.org/details/DFIFAO2.2 https://archive.org/details/DFIFAO2.2/page/n69/mode/2up Emma Brunner-Traut, Egyptian Artists’ Sketches. Figured ostraka from the Gayer-Anderson Collection in the Fitzwilliam Museum Cambridge, Cambridge, 1979

The donors of the Louvre, Paris, Musée du Louvre, 1989

Perfumes and cosmetics in ancient Egypt, exhibition catalogue, Cairo, Marseille, Paris, 2002, p. 99, 139, ESIG, 2002

Anne Minault-Gout, Stone notebooks: the art of ostraca in ancient Egypt, p. 36-37, Hazan, 2002

Guillemette Andreu, The artists of Pharaon. Deir el-Medina and the Valley of the Kings, exhibition catalog, Paris, Turnhout, RMN, Brepols, p. 113, no. 53, 2002

Guillemette Andreu, The Art of Contour. Drawing in ancient Egypt, exhibition catalog, Somogy éditions d’Art, p. 320, ill. p. 320, no. 168, 2013

Marie-Lys Arnette, Postpartum purification and relief rites in ancient Egypt, Bulletin of the French Institute of Oriental Archeology (BIFAO), 114, 2015, p. 19-72, p. 30-31, fig. 2, IFAO, Cairo 2015

Hanane Gaber, Laure Bazin Rizzo, Frédéric Servajean, At work, we know the craftsman… of Pharaon! A century of French research in Deir el-Medina (1917-2017), exhibition catalogue, Silvana Editoriale, p. 36, 2017

Aladin, this is a wonderful post, thank you for sharing more of Marie’s Egyptian magick! I love their celebration of birth and how those scenes have been forever immortalised in their art (we don’t see this happening so much nowadays!)

One of the first things I thought when reading was how unnatural hospital births can be for women in this age, as squatting, seems the best position to get into, rather than being encouraged to give birth lying on one’s back.

Myself, I gave birth first on my back, (which was pure agony!) but the next time I intuitively knew this was not the way to deliver a child so I refused to lay down and be controlled by the doctors and insisted on giving birth in a squatting position.

Honestly, it was the greatest moment of my life! Minimal pain, full involvement, instant bonding, it was an act of pure love. As you can guess this post has moved me to remember both precious births. Love and light, Deborah.

LikeLiked by 1 person

The ring in my head was in the right way, then! It was surely a courageous and great moment for you, my dear Deborah. I remember when I was working as an actor; we learned Yoga, and one of my colleagues got pregnant by giving birth, she had used the breath technique we had learned on set. She said she had barely any pain. Thank you for sharing your memory on this significant subject.🙏🤗💖

LikeLiked by 1 person

Magnificent! This may be my new favorite blog post by you!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, bro. Much appreciated.🤙🙏

LikeLiked by 1 person

You’re welcome!

LikeLiked by 1 person

As always, your post fascinated me and made me reflect on the unnatural position they made people assume in the hospital at the time of birth (I don’t know now).-

Lying on our back, to make work easier for doctors and midwives but not for the future mother, for whom the position is more tiring

I protested at the time of the birth of my second son, I said I didn’t want to lie down but to squat, but there was nothing to be done

LikeLiked by 1 person

I wish I could experience this unique way of creation. However, as a man, I have no chance, but I can imagine how it feels better not to lay as it looks unnatural and instead to do it to the natural state. We might not depend on the newest technique, but we should look into natural ways to comprehend the main point. Grazie, mia cara, cara Amica.💖🙏😘🥰

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you very much for your precious reflection, dearest Aladin 🙏🌹🙏

Wishing you a happy Saturday

LikeLike

Having never given birth myself, I can only comment on my mothers experiences in hospital which were so horrific for her first child that she had me and two more children at home, doing it her way. As a therapist I know that ergonomically, squatting positions and water births are far more natural and less likely to cause problems than the regimented expectations of many hospital midwives…as are additional elements such as burning essential oils and incense. It’s really interesting to see that these techniques were used in ancient Egypt and I’m sure these elements come from knowledge passed down from those and other ancient civilisations.

You’ve got me thinking here Aladin, so expanding the theme but looking at this from another angle, giving birth to creative projects and books can also be both painful and uncomfortable. For me ‘labouring’ over the design, wording, image content of a book has led to many a sleepless night and pain as I have to exclude favorite images or ponder changes to be made to text…at the end of the day there is no easy way to give birth (however defined) apart from just getting comfortable and letting it all flow out!

LikeLiked by 2 people

Dear Lin. As I understood correctly, your mother was terrified of giving birth and transferred it to her children. That is undoubtedly sad. However, you, as an artist, must carry this pain of birth every time, as I know how challenging it is. It is even harder to create new art because an artist has to make not only the body but also breathe the soul into it.

Letting it all flow out: that might be the best way! 🤗🙏💖🌟

LikeLiked by 1 person

You almost got it right Aladin – my mother gave birth at home to three of us because her first experience of childbirth was so bad in hospital, but she didn’t make me fearful of it. You are right though from a creative perspective for me as an artist – hmm…there’s much to think about!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Now, I have comprehended much better; thank you!🙏🤗

LikeLiked by 1 person

I never had any children, but I’ve heard many positive things about water births, in today’s world.

It seems the ancient Egyptians were ahead enough in some ways to be in the 21st century. That would include the allure of make-up.

This is interesting, as some in the surrounding geography still seem to be living in a past calendar.

Also, that some of their “sketchpads” to present the ideas are still here is wonderful.

I always enjoy your posts on ancient Egypt.

Thank you, Aladin.

❦🌹❦🌹❦

LikeLiked by 1 person

You are right, my dear friend. If we let things go in their natural way, many issues will run more trouble-free and smoothly, like letting the forests grow and the reverse run in their own way. The same applies to humans as they are also by nature! Thank you, and I appreciate your encouragement.🍁💑🙏💖😘

LikeLiked by 1 person

❦🌹🌺💖

LikeLiked by 1 person

I love these images and wished for a birthing chair and a warm tub. I love the Egyptian images like these showing human life. For my first childbirth, I didn’t have much choice and was on my back–convenient for the doctor and horrible for the mother. My baby was whisked away to be weighed and measured. Who cares at a moment like that? For my second birth in a different hospital, I had the support of my husband and a maternity nurse who let me squat, sit, walk, lean, or lie on my side–whatever was comfortable for me. And after the birth, the baby was placed against my heart so I could hold him. What a difference!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Honestly, I try to understand this feeling of a mother who wants to have her newborn child on her breast. I was beside my wife when our son was born, and I had compassion when they took him away at once on the pretext of being born prematurely. Regina was sorrowful about this, and I felt with her. I am glad that you, at least for the second son, had the chance to use the squat form of birth. I don’t understand why most hospitals are against this comfort form. They probably earn more!? Thank you for sharing your memories with me, dearest Elaine. Blessings.💕🦋🤗

LikeLike