Mythology (derived from the Greek word ‘mythos’, meaning ‘story’, and ‘logos’, meaning ‘word’) studies a culture’s sacred narratives or fables, known as myths. These stories explore various aspects of the human condition: good and evil, suffering, the origins of life, place names, cultural values, and beliefs regarding life, death, and deities. Myths reflect a culture’s values and beliefs. Mythology may also concentrate on specific collections of myths, whereas history examines significant past events and real individuals. Central characters in myths include gods, demigods, and supernatural beings. The earliest myths date back over 2,700 years, particularly in the works of the Greek poets Homer and Hesiod. Scholar Joseph Campbell defines four essential functions of myth: metaphysical, cosmological, sociological, and pedagogical.

“The wonder is that the characteristic efficacy to touch and inspire deep creative centres dwells in the smallest nursery fairy tale—as the flavour of the ocean is contained in a droplet or the whole mystery of life within the egg of a flea. Because the symbols of mythology are not manufactured, they cannot be ordered, invented, or permanently suppressed. They are spontaneous productions of the psyche, and each bear within it, undamaged, the germ power of its source.”

-Joseph Campbell / From The Hero With A Thousand Faces

However, we can trace back to the ancient Assyrians, where we discover the epic of Gilgamesh (a form of the name derived from the earlier Sumerian form) and Enkidu. Honestly, whatever I know or feel passionate about that subject, I owe it to Al, my brother, who opened the mysterious gate for me to this fascinating world. We cannot overlook the allure of these stories, which not only expand our imagination but also impart a great deal of wisdom through their narratives. Thus, as Dr Jung emphasises here, possessing a myth is of considerable significance. There may even be some truth hidden within it; who knows?

(Parenthesis open) I have tried to write my usual “two posts,” though it has shown me that I do not quite fit as I usually do! I must confess that she, Resa, spurred me to work, for which I am very grateful. I also thank all my friends who attempted to support me, even if it sometimes sounded like Marie Antoinette’s supposedly quoted remark to the starving people of France: “If there is no bread, let them eat brioche!” Although there is no evidence that she actually said this. Also, I must rest. Nevertheless, I thank you all. (Parenthesis closed)!

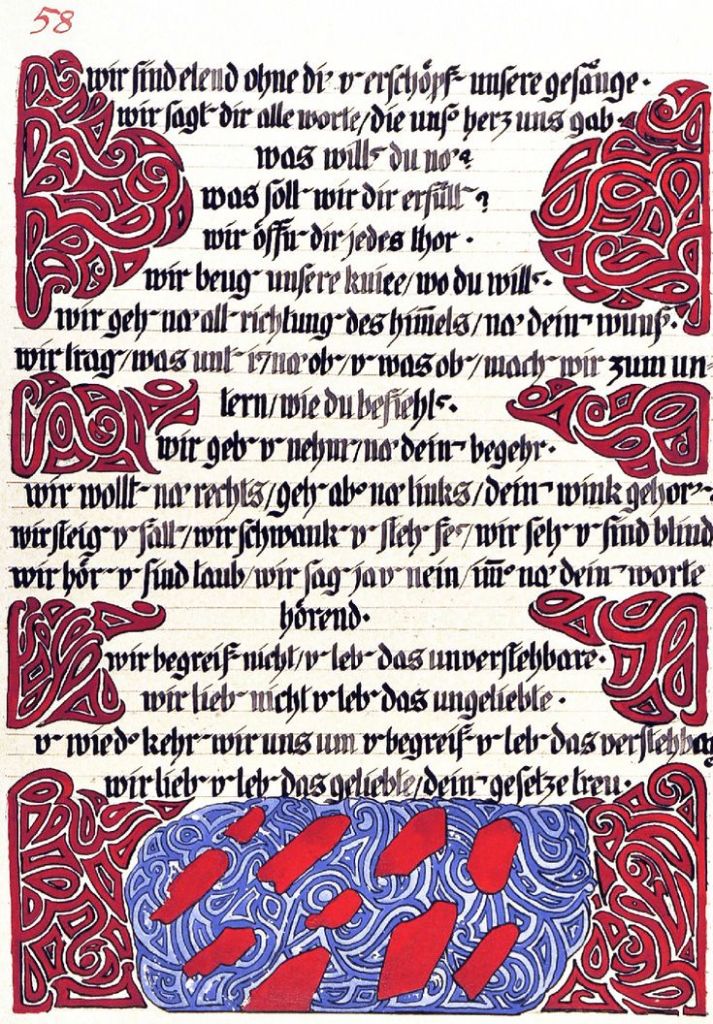

I have selected an intriguing excerpt from the Red Book, Liber Novus, Introduction by Sonu Shamdasani, Reader’s Edition, to share. It illustrates the significance and necessity of having a myth for every individual. I have created a summary to keep it concise!

In 1908, Jung bought land by Lake Zürich in Küsnacht and built a house where he lived for life. In 1909, he resigned from Burghölzli to focus on his practice and research. His retirement coincided with a shift in interests toward methodology, folklore, and religion, leading to a vast private library. This research culminated in “Transformations and Symbols of the Libido,” published in two parts in 1911 and 1912, marking a return to his intellectual and cultural roots. He found this mythological work thrilling; in 1925, he reflected, “It seems to me I was living in an insane asylum of my own making. I went about with all these fantastic figures: centaurs, nymphs, satyrs, gods and goddesses, as though they were patients and I was analysing them. I read a Greek or a Negro myth as if a lunatic were telling me anamnesis. (Introduction to Jungian Psychology, p. 24). The late nineteenth century witnessed a surge in comparative religion and ethnopsychology scholarship, with primary texts being translated and examined, such as Max Müller’s “Sacred Books of the East,” which Jung owned, offering a global relativization of Christianity worldwide.

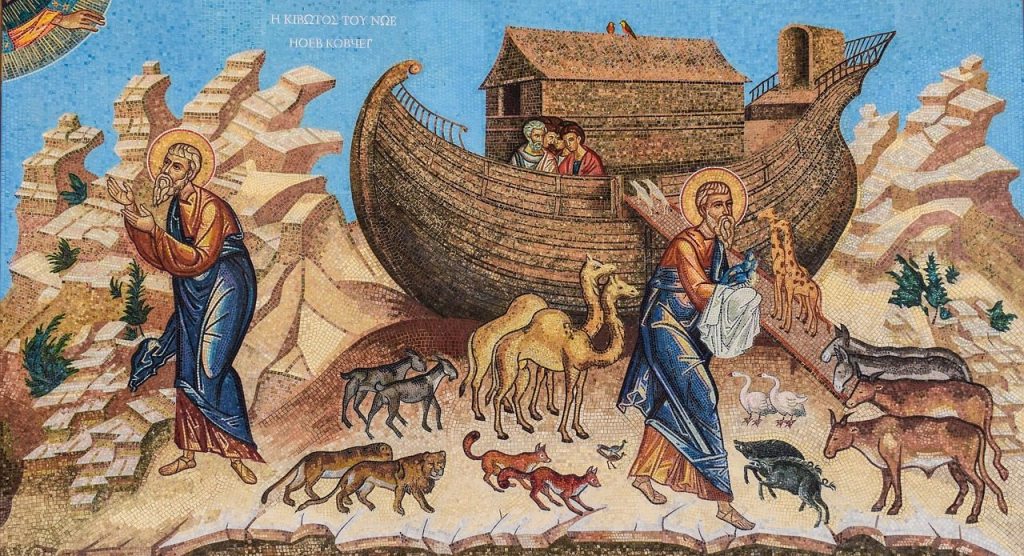

In Translations and Symbols of the Libido, Jung differentiated two types of thinking: directed and fantasy thinking. The former is verbal and logical, exemplified by science, while the latter is passive, associative, and imagistic, represented by mythology. Jung argued that the ancients lacked directed thinking, a modern development. Fantasy thinking occurs when directed thinking ceases. This work extensively studies fantasy thinking and the mythological themes present in contemporary dreams and fantasies. Jung linked the prehistoric, primitive, and child, suggesting that understanding adult fantasy thinking illuminates the thoughts of children, savages, and prehistoric people. (Jung, The Psychology of the Unconscious, CW B, s36. His 1952 revision clarifies this [Symbols of Transformation, CW 5, s29]. In this work, Jung synthesized 19th-century theories on memory, heredity, and the unconscious, proposing a phylogenetic layer of mythological images present in everyone. He viewed myths as symbols of libido, reflecting its movements, and used anthropology’s comparative method to analyze a wide range of myths, calling this “amplification.” He argued that typical myths correspond to ethnopsychological developments of complexes. Following Jacob Burckhardt, he referred to these as “primordial images” (Urbilder). One key myth, that of the hero, represents an individual’s journey to independence from the mother, with the incest motif symbolizing a desire to return to the mother for rebirth. Jung eventually hailed this discovery as the collective unconscious, though the term emerged later.

Myth!

In a series of articles from 1912, Jung’s friend and colleague Alphonse Maeder argued that dreams had a function other than that of wish fulfilment, which was a balancing or compensatory function. Dreams were attempts to solve the individual’s moral conflicts. As such, they did not merely point to the past but also prepared the way for the future. Maeder was developing Flournoy‘s views of the subconscious creative imagination. Jung was working along similar lines and adopted Maeder’s positions. For Jung and Maeder, this alteration of the conception of the dream brought with it an alteration of all other phenomena associated with the unconscious.

In his preface to the 1952 revision of Transformations and Symbols of the Libido, Jung wrote that the work was written in 1911 when he was thirty-six: “The time is a critical one, for it makes the beginning of the second half of life, when a metanoia, a mental transformation, not infrequently occurs (CW 5, p. xxvi). He added that he was conscious of the loss of his collaboration with Freud and was indebted to the support of his wife. After completing the work, he realised the significance of what it meant to live without a myth. One without a myth “is like one uprooted, having no true link either with the past, or with the ancestral life which continues within him, or yet with contemporary human society (Ibid. p. xxix).

As he further describes it:

“I was driven to ask myself in all seriousness: “What is the myth you are living?” I found no answer to this question and had to admit that I was not living with a myth, or even in a myth, but rather in an uncertain cloud of theoretical possibilities, which I was beginning to regard with increasing distrust … So, in the most natural way, I took it upon myself to get to know “my” myth, and I regarded this as a task of tasks –for—so I told myself—how could I, when treating my patients, make due allowance for the personal factor, for my personal equation, which is yet so necessary for a knowledge of the other person, if I was unconscious of it?” (Ibid.)

The study of myth had revealed to Jung his mythlessness. He then undertook to get to know his myth, his “personal equation”. (Cf. Introduction to Jungian Psychology, p. 25) Thus, we see that Jung’s self-experimentation was, in part, a direct response to theoretical questions raised by his research, which culminated in Transformation and Symbols of the Libido.

PS: I will add a follow-up to this article in the future. 🙏💖

You must be logged in to post a comment.