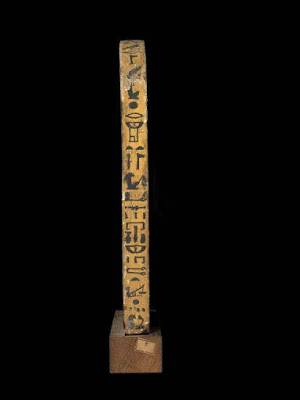

painted wood – origin unknown – gift Batissier

Department of Egyptian Antiquities at the Louvre Museum – E 52 – photo Marie Grillot

Let’s have a look at this stunning Stele, one of the many fascinating Steles from Egypt; the mysterious part of human history.

And here is “The Gate of heaven” or one of the feminine charms of ancient Egypt.

from https://www.nybooks.com/

by; Ingrid D. Rowland

I could imagine that not only for me, but many also have the wish once to pass through this gate! What is always fascinating me when looking at these Steles, they tell us a lot of mystery which mostly are still unknown to us.

Here I try again a translation from the site; https://egyptophile.blogspot.com/ a great description by Marie Grillot about amazing painting Stele.

This so-called “Dame Tapéret” stele is certainly one of the most original artefacts of the Egyptian department of the Louvre museum. Its particularly rich and harmonious chromatic palette seduces us; the originality of the scenes which appear on each of the faces delights us, and the very representation of Dame Tapéret, all in femininity, charms us … As for the symbolism, it is exposed in every detail.

Referenced E 52, 31 cm high, 29 cm wide, 2.6 cm thick, dated from the XXIInd dynasty (approx. 900 BC), it is made of painted wood and of a curved shape. Indeed, as Auguste Mariette reminds us: “Until the 11th dynasty, the steles are quadrangular … But from the 11th dynasty, the stele takes the form that it only abandons on rare occasions. is rounded from above, as if it were intended to recall the curvature of the sky or that of the sarcophagus lids. “

painted wood – origin unknown – gift Batissier

Department of Egyptian Antiquities at the Louvre Museum – E 52

On both sides, Dame Tapéret, the “dedicatee” of the stele, is dressed in a light, pleated, orange-coloured dress, with long and long sleeves, edged with bangs on the front. Completely transparent – we imagine it made in the finest linen – it suggests the curves of the body, especially the arch of the kidneys and the shape of the legs. Tapéret is wearing a long black tripartite wig, encircled by an orange band and surmounted by a delicate cone of perfume. It is adorned with a large necklace with several rows in green tones.

As a sign of adoration, her delicate hands are raised before the god Re whose representation differs from one face to the other.

painted wood – origin unknown – gift Batissier

Department of Egyptian Antiquities at the Louvre Museum – E 52

The front of the stele is an enchantment, a profusion of colours, symbols and charming details. The hanger is fully occupied by the curved sign of the sky which rests and seems to rest on the heraldic plants of Egypt. A set of three stems, artistically positioned, on one side of the lotus and on the other of papyrus, adorn the opposite sides of the stele. The plants seem to “be born”, to spring from a human head which could be that of the god Nefertoum who, as “personification of one of the receptacles of the sun of the origins, is in connection with the perpetual rebirth of the star”.

painted wood – origin unknown – gift Batissier

Department of Egyptian Antiquities at the Louvre Museum – E 52 – photo Marie Grillot

The upper part is occupied, in its centre, by a representation of the conception of the world. The sun, orange and majestic, seems to be surrounded by two uraeus whose heads, erected on either side of its lower part, carry an ankh cross. On each side of the sun is an oudjat eye. The unit thus formed gives an impression of perfect balance.

Under the right eye is a rectangle made up of six vertical lines of hieroglyphs, coloured, which stand out against an ocher background.

The rest of the panel is occupied by a magnificent scene, whose highly accomplished pictorial quality is matched only by extreme originality.

Tapéret, which we described above, stands in front of Re-Horakhty with the head of a falcon. The god with grey flesh is wearing a black tripartite wig. Her muscular body is perfectly proportioned. She wears a green top with suspenders and a loincloth of two colours – orange and beige – held by a belt. It is adorned with many jewels, a large necklace, bracelets of humerus, wrist and ankle. In the left hand, she holds firmly a light green was sceptre as well as a striped stick while, in the right, there is a flail and an ankh cross. The orange solar star which is on its head darts its powerful rays symbolized by four rows of blooming and multicoloured flowers which go towards the face of the deceased. “Figured like multicoloured garlands of lily flowers, these rays bring it the promise of survival in the afterlife …”

painted wood – origin unknown – gift Batissier

Department of Egyptian Antiquities at the Louvre Museum – E 52 – photo Marie Grillot

{detail of the tapeter stele – unknown provenance – stuccoed and painted wood – “The mistress of the house tapéret raises her arms in adoration before the re-horakhty god. the god with the head of a hawk carries on his head the solar star which illuminates the emptying of the woman. Figured like multicolored garlands of lily flowers, these rays bring her the promise of survival in the afterlife. ” (quotation text andreu in “the ancient egypt in the louvre”)}

Between the two figures is a table of offerings laden with food. A caring hand has placed delicate lotus flowers on it. On one side of the table, the leg is an elongated container, decorated with a flower, while the other is occupied by a delicately flowering branch. Dame Tapéret “offers Re a table heavily stocked with food, while the hieroglyphs placed behind her back assure her for herself” thousands of bread, beers, meats and poultry “, according to the millennial formula which allows humans to enjoy eternal sustenance. “

On the back of the stele, Tapéret reproduced identically, is in front of Atoum, “form of the sun god at sunset which echoes Rê-Horakhty, the sun of the day”. He appears without his “human” form, proudly wearing the double crown, in orange tones. Its flesh is grey, the curved false beard is treated in black. He is dressed and dressed in the same way as on the other side. What he holds in his hands are different, however: in the left an ouas sceptre and, in the right, a cane and an ankh cross. In the right centre of the upper part, there is also a rectangle made up of 6 vertical lines of hieroglyphs.

painted wood – origin unknown – gift Batissier

Department of Egyptian Antiquities at the Louvre Museum – E 52

The body, night colour, of the beautiful goddess Nut, long but folded, hugs the entire border of the stele. Its slender legs occupy the entire left part, while its long torso stretches in the hanger, and its head and arms with hands stretched down to occupy the right part.

The pubis is marked with a black triangle and in front of it is a small ocher-red circle which represents the sun, and which is found twice: in the centre of the hanger and at the level of the mouth. “Dream sails on a river originating near the pubis and in the evening she engulfs it in her mouth to revive it every morning.”

The torso, thin and long, is decorated with eleven stars; the breasts are pointed and small. The face of the goddess is in the roundness of the hanger and her long hair descends in a long black cascade to the level of her wrists.

Hieroglyphs “arranged in a retrograde manner above Tapéret exhort these gods to grant to the deceased all the offerings that will be necessary for her to survive in the afterlife”.

In these scenes of worship in the sun is manifested the wish of the deceased to eternally accompany the god Re on his night journey and to be reborn with him each morning. The feet of the god as well as those of Tapéret are bare: they rest on a black band which is at the bottom of the stele and which symbolizes the earth.

painted wood – origin unknown – gift Batissier

Department of Egyptian Antiquities at the Louvre Museum – E 52

It should be noted that “an inscription painted on the edge invokes the divinities Isis, Nephthys, Sokar and Hathor so that they grant to the Lady Tapéret all the funeral offerings necessary for her survival”.

The origin of this stele, the “composition of which combines traditional elements and plastic innovations” remains unfortunately unknown.

She entered the Louvre, thanks to a donation from Louis Batissier. This doctor, art lover, inspector of historic monuments in the Allier in 1839, was, after several charges, appointed consul of France in Suez in 1848. He stayed there for thirteen years, and, befriending Auguste Mariette, was passionate about Egyptology. He built up a fine collection of antiques and it was in 1851 that he offered the stele to the Paris museum, as well as vases, papyrus, amulets …

Sources

” Stele of Lady Taperet ” (Louvre)

Ancient Egypt at theLouvre, Guillemette Andreu, Marie-Hélène Rutschowscaya, Christiane Ziegler, 1997

The gates of heaven: worldviews in ancientEgypt, March 2009 Jocelyne Berlandini Keller, Annie Gasse, Luke Gabolde

Egyptology at the Dawn of the Twenty-first Century: Proceedings of the Eighth International Congress ofEgyptologists, Cairo, 2000, Volume 2, Lyla Pinch Brock; American University in Cairo Press, 2003

Egyptian mythologydictionary, Isabel Franco, 2013

Universal Exhibition of 1867. Description of the EgyptianPark, Auguste Mariette, 1867

Donors of theLouvre, Paris, Louvre 1989

” Louis Batissier ” (INHA)

Christ before Pilate, Mihály Munkácsy, 1881

Christ before Pilate, Mihály Munkácsy, 1881

You must be logged in to post a comment.