As the Greek geographer, Strabo might mean these giant volumes were singing or speaking, or, as Tacitus says, like the “sound of a human voice,” or as Pausanias evokes, the sound of “a string of a cithara or lyre that breaks.” In any case, Memnon greets each morning, at sunrise, the appearance of Eos (Dawn), his mother.

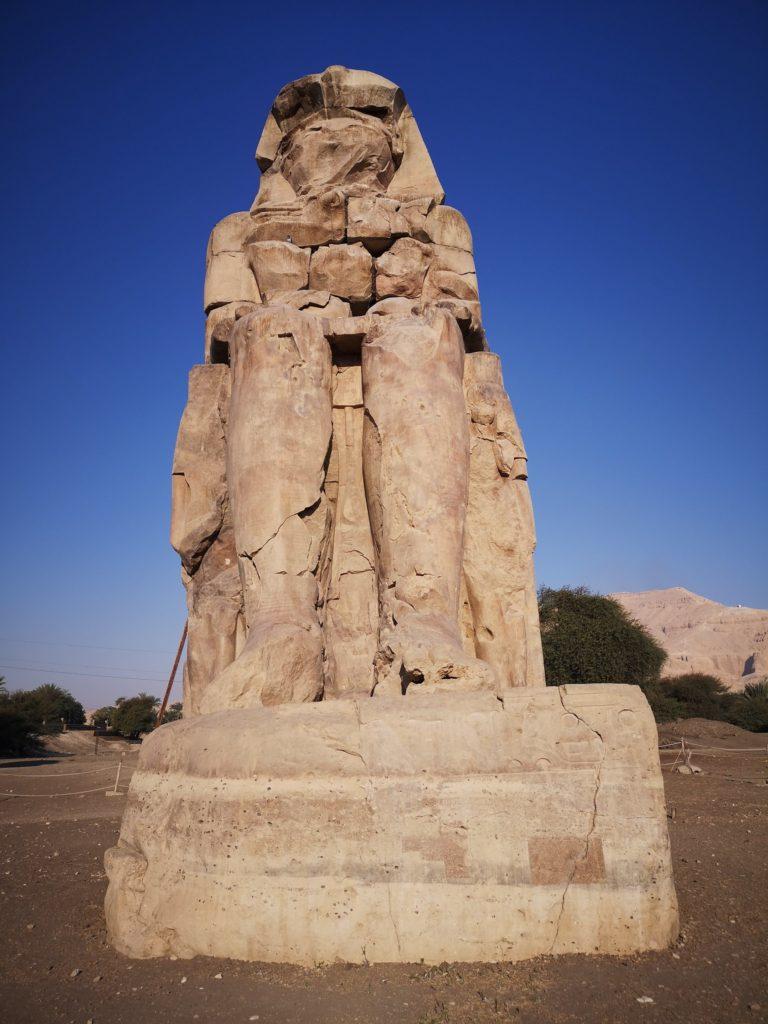

The Colossi of Memnon are two massive stone statues of the Pharaoh Amenhotep III, standing in front of the ruined Mortuary Temple of Amenhotep III, the largest temple in the Theban Necropolis. Via Wik.

Now, let’s delve into the captivating tale of these two enormous statues with sincere gratitude to Marie Grillot and the late beloved Marc Chartier.🙏💖🙏💖

It was at the time when Memnon sang…

of his temple of millions of years, the Amenophium, on the west bank of Thebes.

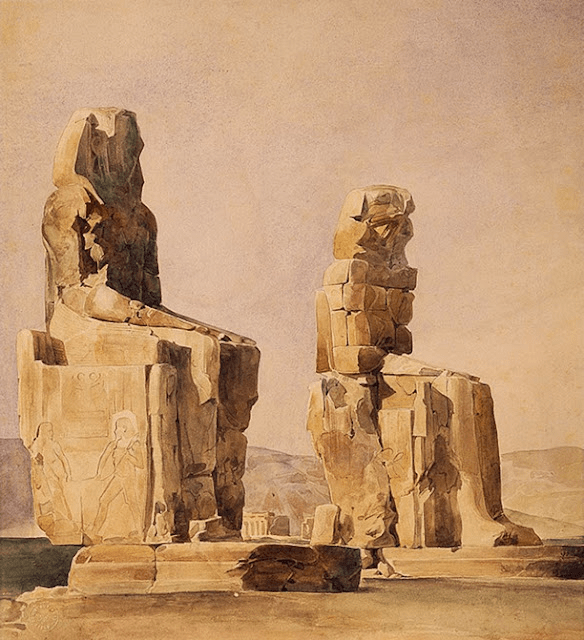

“The Colossus of Memnon” is the one in the north (on the right); it was the only one to sing in antiquity

Photochrome “The Colossi of Memnon”, Photoglob Zurich, circa 1897

via égyptophile

What is called “The Colossi of Memnon” are more “rightly” two monumental stone statues (between 17 and 20 m high) representing Amenhotep III, seated on his throne, facing the rising sun. They stood on the forecourt of his temple of millions of years, the “Amenophium”, on either side of the door of the first pylon. Masterfully designed by the great architect Amenhotep, son of Hapu, it was, in the middle of the 18th dynasty, the richest and largest cult complex on the West Bank.

“Nebmaâtrê” personally describes: “He made it as a monument for his father Amon, Master of the Thrones of the Two Lands. A splendid temple was made for him on the west bank of Thebes, a fortress of eternity forever, of beautiful white sandstone. Entirely covered with gold, its pavement is adorned with silver, all its doors are of electrum, built very wide, and great and perfect forever” …

But… “sic transit gloria mundi”… Having fallen into decline and then abandonment around the 20th dynasty, its splendour has gone… Its walls and pylons of raw bricks have crumbled while its stones were reused for other buildings. The processional avenue and the surrounding fence have disappeared, the columns have collapsed, the statues have been mutilated, hammered, thrown to the ground or recovered by successors… In 27 BC, a terrible earthquake painfully weakened it, and the impact of the Nile floods was devastating. The pillaging of the 19th century, the rise of the water table and the fire of 1996 dealt it the final blows of grace…

© Musée cantonal des Beaux-Arts de Lausanne

Its glorious past survived only through the presence of these two badly damaged statues for centuries. Only the northern one (on the right) will be—and must be—identified as THE “Colossus of Memnon.”

In antiquity, it was the most degraded of the two, the most cracked, and it is, in a certain way, this “sad state” that will earn it a celebrity will transcend borders… Eclipsing Amenhotep III, the sun pharaoh, the “Memnon” singing in the early morning will become a myth, a divinity!

Indeed, the Greek geographer Strabo (64 BC—between 21 and 25 AD) notes that, according to a local legend, the statue begins to “sing” at sunrise. He also certifies having heard the phenomenon himself without being able to specify the cause. The sound is like “a noise similar to that produced by a small sharp blow.”

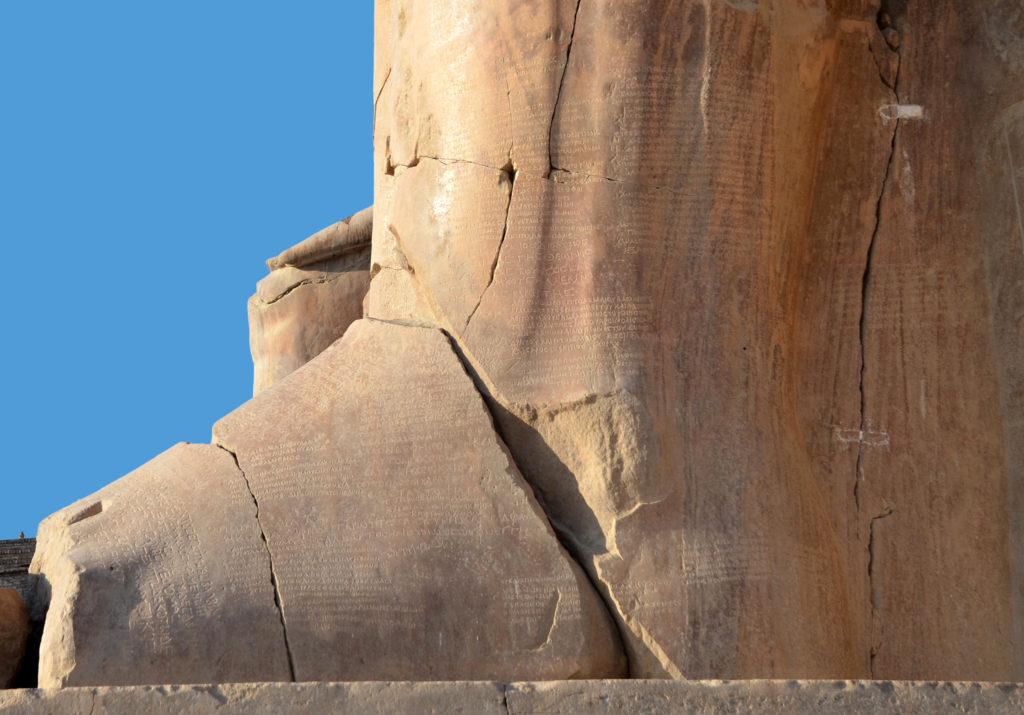

Other testimonies of this phenomenon, very often “immortalized” by graffiti on the monument, will multiply, as diverse as the human imagination can be inventive but concordant on the same observation: the colossus “speaks” or “sings.” Tacitus speaks of the “sound of a human voice,” and Pausanias evokes the sound of “a string of a cithara or lyre that breaks.” Memnon greets each morning, at sunrise, the appearance of Eos (Dawn), his mother.

These two colossi of Amenhotep III stood in front of the 1st pylon

of his temple of millions of years, the Amenophium, on the west bank of Thebes.

Some scholars of the Egyptian Campaign will take note of these various testimonies, privileging reason over fabrication to thwart certain stratagems and the “charlatanism of the priests” intended to feed popular credulity. “It must be noted, in general, that the statue of Memnon has been spoken, with more emphasis, the further away one has moved from the primitive institution of the cult rendered to it. Whatever the nature of the sound coming from the shattered colossus, one cannot doubt that it is the result of a pious fraud. One could indulge here in a host of conjectures, all equally probable, on the mechanism that the priests of Egypt used to produce it…” (Jean-Baptiste Prosper Jollois, Édouard de Villiers du Terrage).

published in “Journey in Lower and Upper Egypt”, Paris, 1802

In the name of an “objective” science, insensitive to the impulses of popular beliefs, Jean-Antoine Letronne, member of the Committee of Historical and Scientific Works, devoted an entire study to the “vocal statue of Memnon”…

As for Baron Taylor, he wrote in 1839 with a certain clarity that “all that is mysterious in the sounds of the statue of Memnon could well have been only a simple effect of the action of the sun on the stone”…

(The Colossi of Memnon, at Thebes, during the Inundation, 19th century), lithograph by David Roberts

In 1840, in the chapter of his “General Overview of Egypt” devoted to minerals, Antoine Barthélémy Clot-Bey provided the following geological explanation: “The agatiferous siliceous breccia of Syene is a stone which is also of great interest. The statue of Memnon, so famous in antiquity, was carved from this type of breccia to the composition of which it doubtless owed the marvellous property which it enjoyed, of making harmonious sounds at sunrise”… This interpretation seems plausible, even if the provenance of the stone remains uncertain… According to Jean-François Champollion, they were “each formed from a single block of breccia sandstone, transported from the quarries of the Upper Thebaid (editor’s note: southern part of the Thebaid), and placed on immense bases of the same material”… But, according to Kent Weeks, the two statues “were sculpted in a beautiful orthoquartzite, a tough stone and very difficult to engrave, brought by boat from the nearby quarries of Heliopolis 700 km to the north (editor’s note: namely Gebel el-Ahmar), or from a quarry in the south – there is no certainty on this matter. Egyptologists believe this stone was chosen because of its red colour, associated with solar worship”.

At the very beginning of the 3rd century, the colossus fell silent. We owe its silence to Septimius Severus, who “before the end of his journey in Egypt in the autumn of 200, wished to see the memorable Memnon and, to restore its dignity, decreed its restoration”. Several courses of blocks gave shape to the torso on which the head was placed… but “From then on, it must be believed that the ‘song’ of the son of the Dawn was never heard again. Nevertheless, his mythical fame crossed the centuries” specifies Christian Leblanc in “Le Bel Occident”…

From this long and incredible story and the various interpretations it has given rise to, there is one note on which we can only agree: the colossus who sang… has made a lot of people talk about him while associating his “twin” with his fame…

of his temple of millions of years, the Amenophium, on the west bank of Thebes.

“The Colossus of Memnon” is the one in the north (on the right); it was the only one to sing in antiquity.

Since 1998, a multidisciplinary European-Egyptian team has been working in Kom el-Hettan on “The Colossi of Memnon and Amenhotep III temple conservation project”. Led by the extraordinary Egyptologist Hourig Sourouzian, it deploys its expertise, know-how and energy to restore this temple’s dignity and grandeur. The different sectors of the Amenophium are identified, the pavements reappear, the bases of the columns are cleared, dozens of Sekhmet emerge from the ground, and the royal statues are reassembled…

Thus, It is pleasant to think that if Memnon were to feel the desire to sing again, it could only be a hymn of recognition for his rebirth!

Sources:

Jean Baptiste Prosper Jollois, Édouard de Villiers du Terrage, René Edouard Devilliers du Terrage, Description générale de Thèbes : contenant une exposition détaillée de l’état actuel de ses ruines, et suivie de recherches critiques sur l’histoire et sur l’étendue de cette première capitale de l’Égypte, 1813 Jean-François Champollion, Lettres écrites d’Égypte et de Nubie en 1828 et 1829, (16e lettre), Paris, 1833 Jean Antoine Letronne, La statue vocale de Memnon considérée dans ses rapports avec l’Égypte et la Grèce – étude historique faisant suite aux recherches pour servir à l’histoire de l’Égypte pendant la domination des Grecs et des Romains, Imprimerie Royale, Paris, 1833 https://books.google.fr/books?id=k26BIIn7C5UC&printsec=frontcover&hl=fr&source=gbs_ge_summary_r&cad=0#v=onepage&q&f=false Baron Taylor, Louis Reybaud, Syria, Egypt, Palestine and Judea considered under their historical and archaeological aspect…, Paris, 1838 https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k1040108x.image Antoine Barthélémy Clot-Bey, General overview of Egypt, Fortin Masson et Cie Libraires Editeurs, Paris, 1840 http://www.lacabalesta.it/biblioteca/ClotBey/AperGenEgypte/clotbey1_02.html#nat_01 Jean-Antoine Lettrone, Collection of Greek and Latin inscriptions of Egypt, Royal Printing Office, 1842

André and Étienne Bernand, Greek and Latin inscriptions of the Colossus of Memnon, IFAO, Cairo, 1960

André Bernand, The singing statues of Amenhotep III, Clio, 2001 https://www.clio.fr/BIBLIOTHEQUE/pdf/pdf_les_statues_chantantes_damenophis_iii.pdf Amenophis III, the sun pharaoh, Réunion des musées nationaux, 1993

Kent Weeks, Illustrated Guide Luxor, tombs, temples and museums, White Star Publishers, 2005

Galand David, The song of the statue: the myth of Memnon in the 19th century, Loxias 22, 2008 http://revel.unice.fr/loxias/index.html?id=2439. Christian Leblanc, Angelo Sesana, The Beautiful West of Thebes Imentet Neferet, From the Pharaonic era to modern times – A history revealed by toponymy, L’Harmattan, 2022

The colossi of Memnon and Amenhotep III temple conservation project – Hourig Sourouzian, articles available on Academia https://independent.academia.edu/HourigSourouzian

Very well written and great photos!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you so much, dear friend.🙏

LikeLiked by 1 person

Wow, I’m blown away by the awe and the majesty of these giant statues that once acted as true guardians to that ruined temple. Oh, what stories they could tell us, ad infinitum! Thank you so much Aladin for sharing more of Marie’s Egyptian magick and mythology. Love and light, Deborah.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Oh yes! That story they would tell must be very intriguing. Thank you, dear Deborah, for your kind words.🥰🙏

LikeLiked by 1 person

Wow. This is wonderful!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Indeed, dear Chris. That is gigantic!🙏💖

LikeLiked by 1 person

Wow, what incredible sculptures – yet another masterpiece from the craftspeople of that time. These tales are always so fascinating to hear Aladin!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Indeed, dear Lin. I am always excited to find some other fascination. Thank you!🤗🙏🌺

LikeLiked by 1 person

Fascinating.

The art, all of the arts, are the true legacies of a society’s cultural existence.

These 2 statues are a testament to that.

Thank you, Aladin. I’m always keen to read your posts on Egypt!

🌹❦💓xoxo

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, my lovely friend. As you well said, these are testaments to our ancient times, and we might try to get the messages.

Have a great week ahead.🙏🤗🌹💖

LikeLiked by 1 person

Welcome, and you too! ❦🌹💓🌟

LikeLiked by 1 person

Appreciate this history and the detailed photos!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Heartfelt thanks, dear friend. 🙏

LikeLiked by 1 person

You are welcome!

LikeLiked by 1 person