The Temple of Amun is an archaeological site at Jebel Barkal in Northern State, Sudan. It is about 400 kilometres (250 mi) north of Khartoum near Karima. The temple stands near a large bend of the Nile River in the region called Nubia in ancient times. The Temple of Amun, one of the largest temples at Jebel Barkal, is considered sacred to the local population. Not only was the Amun temple a leading centre of what was once considered an almost universal religion but, along with the other archaeological sites at Jebel Barkal, it was representative of the revival of Egyptian religious values. Up to the middle of the 19th century, the temple was subjected to vandalism, destruction, and indiscriminate plundering before it came under state protection.

by AlexAnton

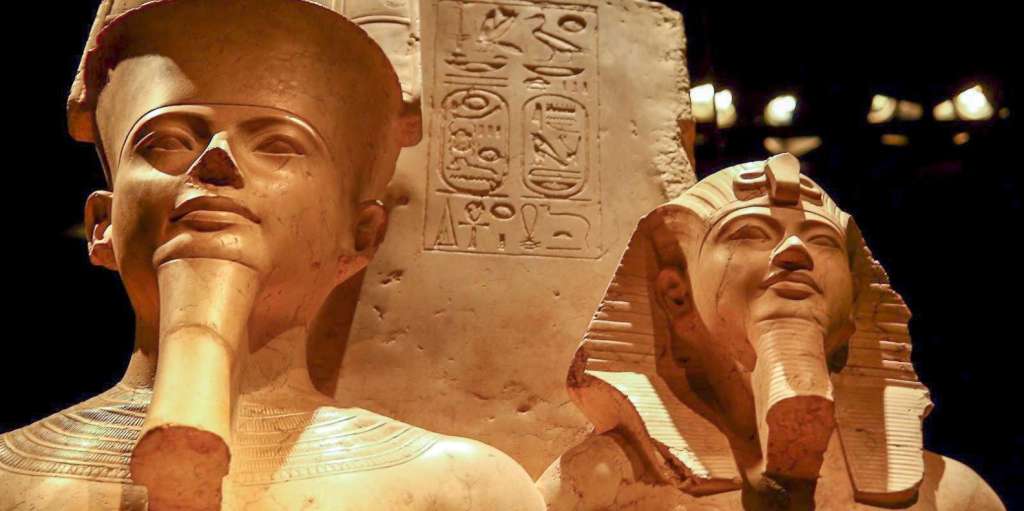

The image above is a limestone sculpture depicting the Gods Amun and Tutankhamun. XVIII Dynasty, 1333-1323 BCE, from the Temple of Amun, Thebes. (Egyptian Museum, Turin)

Here is an excellent, elegantly written report by Marie Grillot about this discovery.

The Statuary Group of Amun and Tutankhamun from the Turin Museum

Arrived at the Egyptian Museum in Turin through the acquisition of the Drovetti Collection in 1824 – C. 768

via égyptophile

This statuary group, 2.11m high, sculpted in magnificent white limestone, sits at the entrance to the Galleria del Rei (gallery of the kings) of the Egyptian Museum in Turin.

Dated from the New Kingdom, from the 18th dynasty, it represents the Theban god Amun-Re, seated on a throne, with to his left, on a much smaller scale, a pharaoh, who is standing.

Amon, recognizable by his characteristic flat hairstyle topped with two tall stylized ostrich feathers, is “ideally” handsome, with a face and body of perfect proportions.

In 1824, in his “Letters to Mr. the Duke of Blacas d’Aulps relating to the Royal Egyptian Museum in Turin”, Jean-François Champollion described it as follows“ “The main figure, which represents the most powerful of the divinities of Egypt, Amon-ra, (Ammon), was no less, although seated, than eight feet in height; he is now only six feet three inches, the upper parts of the hairstyle being today destroyed. The king of gods is represented with a human head whose features, full of grandeur, are executed with admirable finesse of work.

Discovered in 1818 at the Temple of Mut in Karnak by Jean-Jacques Rifaud on behalf of Bernardino Drovetti

Arrived at the Egyptian Museum in Turin through the acquisition of the Drovetti Collection in 1824 – C. 768

He wears a false beard and is adorned with a large necklace “with eight rows ending in beads in the shape of pears”. His torso is absolutely perfect, punctuated by the swell of the chest and the slight hollow of the navel. He is dressed in a single-pleated linen loincloth that reaches above the knee. His forearms, decorated with bracelets, rest on his thighs and, in his right hand, he firmly holds the sign of life“ “ankh”.

The powerful legs help to accentuate the impression of strength and stability; the feet are bare.

The pharaoh who stands next to him is slightly behind. Its size, much smaller, reflects the “recognition of God’s omnipotence and the fact that he places himself under his protection. With his right arm, he surrounds the shoulders of the divinity.

Discovered in 1818 at the Temple of Mut in Karnak by Jean-Jacques Rifaud on behalf of Bernardino Drovetti

Arrived at the Egyptian Museum in Turin through the acquisition of the Drovetti Collection in 1824 – C. 768

He wears the uraeus nemes and the false beard. His face is sculpted very precisely. “The face modelled in an elongated and triangular way, the upper lip arched with drooping ends, the lower lip a little swollen and protruding, finally the furrow of the lips which cannot be said to be rectilinear, but rather slightly sinuous, all these particular traits of Tut-Ankh-Amon, we find them on the face of the statue. These are the same conventions which mark the effigy of the pharaoh as immortalized in his best status,” analyzes Ernest Scamuzzi in “Egyptian Art at the Turin Museum”.

His gaze looks far away. “The eyes are represented in hollow orbits with half-closed eyelids, unlike pre-Amarna faces, whose features were graphically applied to a flat frontal plane and underlined with strongly artificial lines which joined the lines of the makeup”, specifies Eleni Vassilika in “Art Treasures of the Museo Egizio”. And she adds: “The king has a high waist, a prominent abdomen, and, to accentuate it, the belt of his loincloth is lowered in the front.” Thus, we can also read reminiscences of the Amarna era in how the sculptor treated the body.

The garment, which we imagine to be made of finely pleated linen, is nicely worked, particularly on the belt and on the central panel, which falls longer. He has, just like ”his” God, bare feet.

Does this statue really represent Tutankhamun? Or his successor, Horemheb, because it is impossible to hide the fact that the statue bears his name…

Arrived at the Egyptian Museum in Turin through the acquisition of the Drovetti Collection in 1824 – C. 768 (museum phot“)

“In reality, the king’s Amarna features are so convincing that they suggest this sculpture could be a product of Akhenaten’s immediate successor, King Tutankhamun,” says Eleni Vassilika.

It may also be a usurpation “common phenomenon in royal circles. “… And it is interesting to read this interpretation by Ernest Scamuzzi: “If the name of the successor of Tout-Ankh-Amon, Horemheb, whose reign put an end to the 18th dynasty, is engraved to the right and left of the front face of the throne of Amun, and in the two lines of text which are engraved at the top and the right of the pharaoh, it does not follow that we must, on the sole testimony of more recent use, attribute to Horemheb the first initiative of this group begun but not completed, perhaps because of the brevity of his reign, by Tut-Ankh-Amon.

Thus, this statue is undoubtedly linked to the “restoration” of the cult of the Theban god Amon by the successors of Amenhotep IV – Akhenaten (who had, we remember, imposed the cult of a single god, Aton).

This statuary group comes from the large Karnak complex. Dedicated to the Theban triad, it is made up of three distinct groups: the Montou enclosure, the large buildings dedicated to Amon Ré and the Mout domain. It is precisely in this last area – which extends around ten hectares south of the large temple to which a dromos connects it – that it was found.

Arrived at the Egyptian Museum in Turin through the acquisition of the Drovetti Collection in 1824 – C. 768

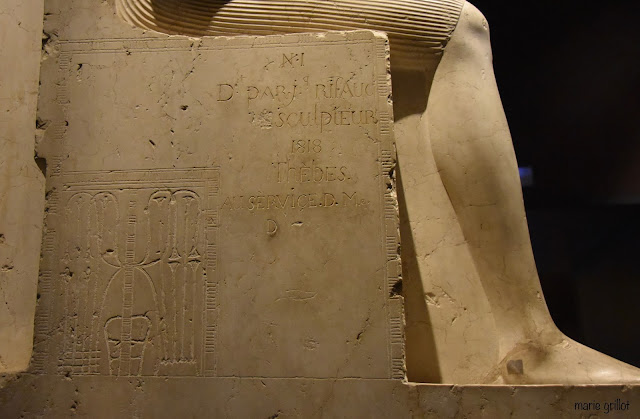

Inscription engraved by the discoverer

As evidenced by the inscription engraved on the right side of the throne, “N1 Drt by Jq Rifaud sculptor. 1818 Thebes IN THE SERVicE of D. M. D”, the discovery was made by Jean-Jacques Rifaud from Marseille who, in 1818, began excavations at Karnak on behalf of Bernardino Drovetti (the “M.D.” of engraving).

Drovetti, of Italian origin, formerly of the Egyptian campaign, was then serving as French consul in Egypt, a post to which he had been appointed in 1803. At age 26, he had thus found, with immense happiness, the land of the pharaohs.

Upon his arrival, this antique enthusiast “ruined himself in antique objects and constituted a collection of first value which commanded the admiration of Chateaubriand”. At the same time, he gave Méhémet Ali the support of the Masonic lodge that he directed, the “Egyptian Secret Society”, and became its advisor. This proximity allowed him to easily obtain the “firman” (permits) to undertake excavations.

behind him, we recognize the energetic face of Rifaud.

(interpretation by Jean-Jacques Fiechter in “The Harvest of the Gods”)

So, to carry out his projects successfully, he recruits several agents. The main ones are the sculptor Jean-Jacques Rifaud and the designer Frédéric Cailliaud – who excavated and researched the most beautiful pieces for him. On the ground, particularly in ancient Thebes, the team came up against the “competitor” of the British consul Henry Salt, who notably employed the great Giovanni Battista Belzoni.

The rivalry is such that the protagonists often show themselves unscrupulous, resorting to disrespectful practices in their frantic race for discovery. What will be called the “war of the consuls” is full of quite extraordinary episodes!

Moreover, the fact that the discoverer engraved his name on the statues was undoubtedly not only a way of “referencing” them but also a good way of not having the authorship of the discovery stolen!

If the consuls constitute their personal collection, they also constitute, at the same time, very important collections which they offer to the sovereigns of certain European countries (mainly Italy, France and England) who wish to create or enrich their museums…

It was precisely in 1824, when His Majesty the King of Sardinia purchased the first “Drovetti” collection, that the statue arrived in Turin. It was referenced C.768.

Sources:

Jean-François Champollion, Letters to M. le Duc de Blacas d’Aulps relating to the Royal Egyptian Museum of Turin, first letter – historical monuments, Turin, July 1824, Firmin Didot, 1824 (pp. 1-92). http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k65247619

Egyptian Museum, Turin Museum of Egyptian Antiquities Foundation, Franco Cosimo Panini Editore, 2016

Art Treasures of the Egyptian Museum, Eleni Vassilika, Allemandi & Co

Museo Egizio guide, editions Franco Cosimo Panini

The Egyptian Museum Turin, Federico Garolla Editore

Egyptian Art at the Turin Museum, Ernest Scamuzzi, Hachette, 1966

The harvest of the gods – The great adventure of Egyptology, Jean-Jacques Fiechter

Table of Egypt, Nubia and surrounding places, or Itinerary for the use of travellers who visit these regions, Jean-Jacques Rifaud, Treuttel et Würtz (Paris), 1830

Topographical bibliography of ancient Egyptian hieroglyphic texts, reliefs, and paintings – II – Theban Temples by the late Bertha Porter and Rosalind L.B. Moss, Hon. D. Litt. (Oxon.),F.S.A.. assisted by Ethel W. Burney, second edition revised and augmented, Oxford at the Clarendon Press, 1972

Posted 7th September 2020

Labels: Amon Champollion Drovetti Karnak Rifaud (Jean-Jacques) Toutankhamon Turin (musée)

This is wonderful!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you very much, my friend. I am incredibly grateful for your support. 🙏🙏🤙🖖👍

LikeLike

I found the post really interesting and the description of the Statuary Group of Amun and Tutankhamun that we have at the Turin Museum fascinating

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, my lovely Luisa. I am glad to know that you enjoyed it.

LikeLiked by 1 person

🙏🙏🙏

This was indeed a very interesting article to read (as always)

LikeLiked by 1 person

Gratitude, dear Luisa. 🙏🤗💖

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for sharing another of Marie’s excellent Egyptian posts. So beautifully presented, I love the attention to detail in her descriptions too. Whatever you’re doing this blessed autumn equinox weekend, I hope you’re having a lovely one. Love and light, Deborah.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I would say I do my best. I’m having a busy week (as always!), and let’s see how far my energy lasts as an older man! Thank you, my lovely angel. 🤗🙏💖

LikeLiked by 1 person

These are beautiful statues Aladin…interesting that the finder signs his name on each one to preserve his part in the story. So many Victorian explorers ruined ancient sites – here in the UK many sacred burial mounds were excavated ruthlessly and the contents taken…nowadays it wouldn’t happen thank goodness. Thank you for posting.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I loudly say Amen! Humans are wayward, but thankfully, some stay aware. Thank you, dear Lin.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Please delete previous comment and we’ll see if this works now. My comment about your blog:

Thank you for sharing this beautiful selection of sculpture. I think of Amun as the focus of monotheism as the “state” religion and then that perspective spread throughout the Middle East. Amun statues usually have a serene face, like these, but monotheism doesn’t have a peaceful history. With gratitude for sharing this post.

LikeLiked by 1 person

True! The specific meaning of this great God Amun, with his serene face, has not been spread through the Middle East; what a pity!

I am pleased you can share your wisdom here with me, dear Elaine. Thank you.

LikeLiked by 1 person

The delusional state of mind of the Pharaonic Egyptians, never ceases to amaze me!!!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Indeed, Brother. I am also stuck in this magic!😉

LikeLike

wonderful and amazing!!:-)) best greetings, my dear:-)

LikeLiked by 1 person

Heartfelt thanks, lovely Corinna. Hugs.🤗🌹

LikeLiked by 1 person