Tahtib is the term for a traditional stick-fighting martial art originally named fan a’nazaha wa-tahtib, “the art of being straight and honest through the use of a stick”. The original military version of tahtib later evolved into an Egyptian folk dance with a wooden stick. It is commonly described in English as a “stick dance”, “cane dance”, “stick-dancing game”, or as ritual mock combat accompanied by music. Nowadays, the word tahtib encompasses both martial practice and performance art. It is mainly practised today in Upper Egypt. Tahtib is regularly performed for tourists in Luxor and Aswan. Stick fighting

The Stick dance was originally a dance style that African–Americans developed on American plantations during the slavery era, where dancing was used to practice “military drills” among the enslaved people, where the stick used in the dance was, in fact, a disguised weapon.

And In Iran, it is also a traditional art: Choob bazi, also known as chob bazi, chub-bazi, çûb-bâzî or raghs-e choob, is a chain dance found all over Iran, performed by men with sticks; the name translates to English as ‘stick play’. There are two types of Choob bazi dance styles, the first one being more combative in style, only performed by men (normally only two men, assuming the roles as the attacker and the defender) and does not appear to have a rhythmic pattern; this style is more frequently found in Southwestern Iran. The second style, Choob bazi, is a circle or line dance with a pattern, performed by both sexes and is more of a social dance. Wikipedia

The stick used in tahtib is about four feet long and is called an asa, asaya, assaya, or nabboot. It is often flailed in large figure-eight patterns across the body with such speed that air displacement is loudly discernible. Wikipedia

Tahtib is a little-known stick-fighting discipline developed during Egypt’s pharaoh period. Its history has seen it used in combat, snubbed by its countrymen, and transformed into a type of folkloric dance before its re-emergence as a martial art in recent years.

Imagine there would never be any fighting between people in the world but the fight between dancing artists!

Anyway, this is a brilliant article by Mr Marc Chartier, an Egyptian journalist, researcher, and adorable friend of mine. It is an old article (June 2016), but still enjoyable.

The Tahtib: the stick that has led the dance since antiquity

via égyptophile

It is sometimes compared to Brazilian capoeira, another art of African origin, because of the role of the public and musical training. However, one noticeable difference is that the tahtib is exercised with a stick, considered an “extension of the body”.

The word “tahtib” is derived from “hatab”, which means “firewood”. From there, imagine that this playful and sporting practice is synonymous with the art and the way of making your opponent understand “what wood we are warming ourselves with”; there is only one step we will not take! It also bears a complete name that would bring us back on the right track if necessary: “fann al-nazaha wa-l-tahtib”, “the art of purity of heart and the staff”. In other words, bad intentions or the desire to hurt the other jouster would go against the very spirit of tahtib. It would be immediately sanctioned by the public, whose role is to punctuate the players’ evolution and arbitrate when they evolve in a bad spirit by cheating or displaying excessive aggressiveness.

Whereas, until the 19th century, the jousters challenged each other with wooden weapons “strong enough to break a bone”, the outcome of the bloody combat sometimes being death, today the stick of tahtib is made of fibre rattan, a hollow stem from Southeast Asia, to prevent injuries.

“The game is to pass the guard to make an attack, or in Egyptian terminology, to pass ‘the door’ (al-bâb). The winner is the first to touch (graze) his opponent’s head. The fight results in extreme excitement followed by disturbing immobility where the opponents spy on each other and gauge each other while waiting for weakness or the right moment. During the games, there is no question of injuring your opponent; the contacts are symbolic; here, it’s not about actually hitting, but about simulating a fight (it’s all in technique and concentration).” (arts-and-combat-games.fr)

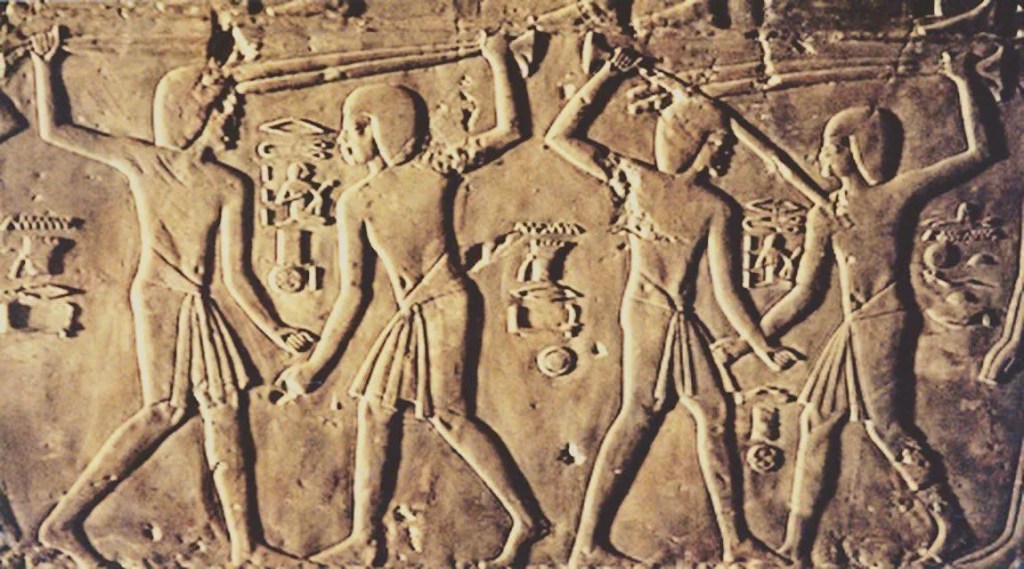

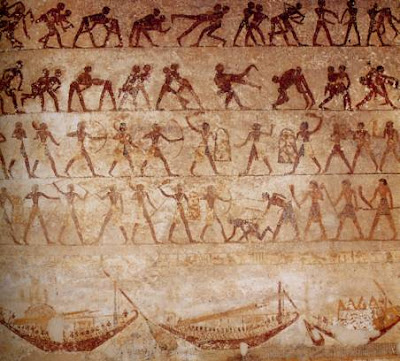

Having become choreography, sporting activity and festive entertainment, the tahtib originates from the Pharaonic era. There are, says the website tahtib.com: “countless traces (engravings and drawings) left on the walls of the tombs of ancient Egypt, from the Old Kingdom to the arrival of Alexander the Great in Egypt (…) The codes of the tahtib are established around 3200 BC, as shown by the excavations carried out by the famous Egyptologist Zahi Hawass in the region of Abu Sir (… ).” The engravings discovered there feature tahtib, among other sporting activities, featuring instructors and their young students.

The tahtib recalls the same source: “appears as much on the walls of the royal pyramids as those of many tombs. (It) was therefore not reserved for a specific social class but shared by all. (…) (It ) crosses the history of Egypt without interruption. Its representations dating from the Middle Kingdom concern soldiers in training. They are visible on the walls of the tombs of Middle Egypt in the necropolis of Beni Hassan in the region of Minya. At the same time, another form of stick combat appeared: the short stick with different codes from the tahtib. Representations of the tahtib continued in the New Kingdom, notably on the walls of tombs in Luxor and those of Saqqara. At that time, the tahtib also became demonstrative. With “danced” steps and gestures, it had a positive intention for the spectators, as is still the case today in Upper Egypt.”

A “martial” art, just like archery and wrestling, the tahtib is, in reality, in its first expression since it was invented and codified to exercise the royal soldiers of the ancient world in combat. Egypt teaches them how to protect themselves against a blow from a stick or reach the opponent’s head without wasting time hitting the stick or elsewhere. Then, over the centuries, peasants and shepherds appropriated this military practice to transform it into a “game of challenges” and a festive activity, accompanied by dances and traditional music, in the villages of the Nile Valley.

This distraction, long relegated to the rank of folklore for weddings, mawlids or other popular festivities, is today once again rehabilitated as a true martial art, thanks to a few enthusiasts, including the Franco-Egyptian Adel Paul Boulad, founder of the association Seiza. Thus: “After seven years of gestation and planning led by Adel Paul Boulad and his teams in Egypt and France, Modern Tahtib was born on March 6, 2014. Modern Tahtib is a martial discipline practised with a stick: fights, rhythms and sequences. “

The Seiza association develops this sporting discipline concerning the “Art du Baton et Tahtib – Medhat Fawzi” Center in Malawi in Upper Egypt.

The instructors of the Medhat Fawzi Center and the Seiza Association highlight the dual dimension – playful and formative – of Modern Tahtib. In 2010, they made a world premiere, a demonstration at the International Festival of Martial Arts in Paris, as well as a first international internship in Egypt. In 2011, they trained five schools in Cairo and organised the first inter-school tahtib tournament. Currently, they are working on creating the Tahtib Academy in Egypt, whose mission will be the artistic development of the activity, its promotion and the training of instructors. Egypt has applied to UNESCO to support initiatives recognising this discipline as an intangible cultural heritage.

“When you have a stick in your hand, specifies Adel Paul Boulad, you first learn to respect the other and yourself. With percussion, you also learn to enter into harmony with the others. (…) The codification of this art removes violence. We transform warlike principles into a principle of self-development through martial art. At the heart of the operation, there is respect.”

As “martial” as it is, the tahtib “conveys universal social and educational values”. An exemplary value that we owe to Egypt!

Sources:

All Sticks, by Thomas Saint-Cricq, “Le Monde” May 17, 2014

Adel Paul Boulad, Modern tahtib, The Egyptian fighting stick, Budo Editions

http://www.tahtib.com/ http://www.tahtib.com/media/articles/IMAtahtib.pdf http://www.egyptos.net/egyptos/actualite-egypte/le-tahtib-un-art-martial-egyptien-pluri-millenaire-vivant.php,406 https://www.facebook.com/Modern-Tahtib-139424397876/ http://club.seiza.free.fr/index.html

Thanks for talking about this martial art that I didn’t know very well, making a long excursus on its history-

Wishing you a lovely Saturday🌹

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, my lovely friend. I knew this kind of dance from Iran as the “anti-war arts”. We might believe that humans will war on this art form someday! 🥰🥰🙏💖😘😘🌹

LikeLiked by 1 person

Unfortunately the real war serves a lot of interests, not patriotic because they are just an excuse, but economic

So any manifestation of anti-war art might not be tolerated🏳️🌈🏳️🌈🏳️🌈

LikeLiked by 1 person

🖤🖤🖤

LikeLiked by 1 person

💖💖🙏💖💖🌹

LikeLike

I associate martial arts with China, Japan and Korea…

LikeLiked by 1 person

Of course, they have a lot of such examples and are also beautiful for sure.🤙

LikeLike

Reblogged this on Have We Had Help? and commented:

Iranian martial arts…

LikeLiked by 1 person

Iranian and Egyptian. Thank you, master.🤙🙏

LikeLike

Thanks for sharing this. I’d never heard of it. It takes lots of skill but I know nothing of martial arts other than a year of judo when I was in college. One wrong move and there is injury, but in that case, there were no sticks.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Well done, Elaine! Judo might help a lot for self-defence and also strength concentration. This one is just a take on the old wars act in dance art, which is definitely much better: enjoyable and bloodless! 😉🙏🤗

LikeLiked by 1 person