Month: April 2019

The Sign of the Black Sun

Standard Black Sun-Toyen 1951

Black Sun-Toyen 1951

My thoughts and as a consequence my dreams have been occupied by Prague lately, (a place I have never visited, incidentally), the city of Emperor Rudolf II with his court of alchemists, magicians, scientists and artists; where Dr John Dee and his medium Edward Kelley conjured up a vast array of angels in a Aztec obsidian mirror and Guiseppe Arcimboldo painted his bizarre composite portraits of visages made of fruit, branches, flowers and books. The city (fast forwarding three centuries) of Meyrink and his Golem haunting the ghetto; of Kafka and his monstrous metamorphoses, bewildering reversals and byzantine bureaucracies. The city of the incomparable Toyen.

Toyen’s phantasmagorical art is filled with images of transformation, of women becoming animals or vice versa, of sudden and terrifying shifts in size and scale, of spectral figures in the process of materialisation, of impossible desires becoming reality. Sometimes…

View original post 145 more words

Published poem- The BeZine Magazine…

StandardMY OLD STRAW HAT

StandardAn impressive meaningful lecture 👍 for me, I had to read it twice to float into 😊🙏

Henri Rousseau: The Dream

Henri Rousseau: The Dream

MY OLD STRAW HAT (a fiction)

a simmering island mass

an entity where moral codes

of both the uncaged, untamed

vertebrates and spineless wild things

long since have fallen foul of tepid

fate’s unearthly indifference

cloaked saturated evergreen

perspiring rooted miscreation’s

of a godforsaken helter-skelter

intemperate jungle uglifying

the less than razzle dazzling

temperate landmass harshly

empty of natural sweet reason

under a prudish expanded canopy’s

demented shadow-dance oblivion

a cacophony of agonizing

‘screeches’

dawn to dust

dusk to dawn

as feathered and crocodilian

battle and openly procreate

under the ever-watchful eye

of wee creepy-crawly beings

liable to both promenade

and scoff the edible remains

of the eternally sickly sticky

dripping days and raw nights

for the main part

well-hidden inland

polished terra-cotta

indigenous tribes of

alleged connoisseurs’

a taste for feeding upon

unseasoned human flesh

whereas at coastal skirts, a

master caste of…

View original post 165 more words

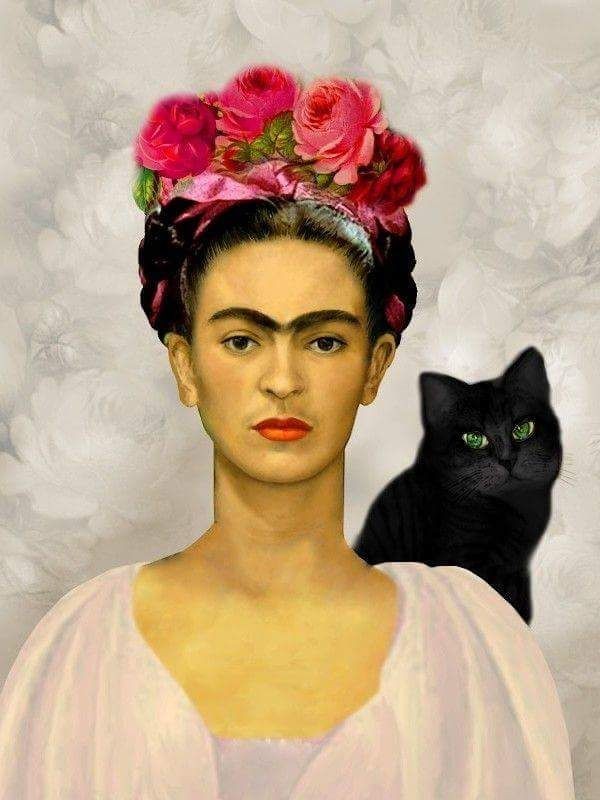

A Brief Animated Introduction to the Life and Work of Frida Kahlo

Standard

via http://www.openculture.com/

A great Fabolous genius Artist ❤ ❤ h

Reducing an artist’s work to their biography produces crude understanding. But in very many cases, life and work cannot be teased apart. This applies not only to Sylvia Plath and her contemporary confessional poets but also to James Joyce and Marcel Proust and writers they admired, like Dante and Cervantes.

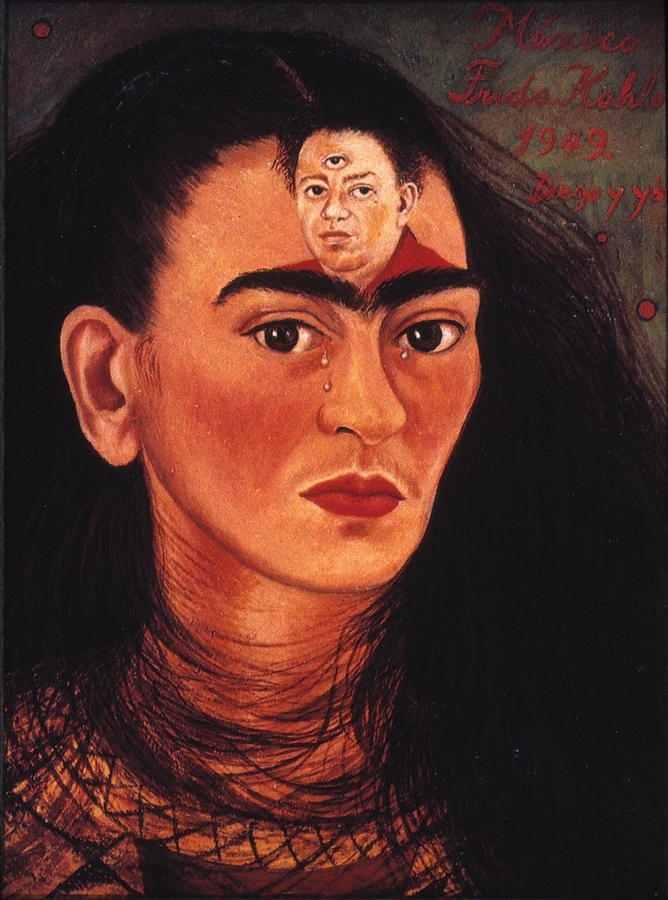

Such an artist too is Frida Kahlo, a practitioner of narrative self-portraits in a modernizing idiom that at the same time draws extensively on tradition. The literary nature of her art is a subject much neglected in popular discussions of her work. She wrote passionate, eloquent love poems and letters to her husband Diego Rivera and others, full of the same kind of visceral, violent, verdant imagery she deployed in her paintings.

More generally, the “obsession with Kahlo’s biography,” writes Maria Garcia at WBUR, ends up focusing “almost voyeuristically—on the tragic experiences of her life more than her artistry.” Those terribly compounded tragedies include surviving polio and, as you’ll learn in Iseult Gillespie’s short TED-Ed video above, a bus crash that nearly tore her in half. She began painting while recovering in bed. She was never the same and lived her life in chronic pain and frequent hospitalizations.

Perhaps a certain cult of Kahlo does place morbid fascination above real appreciation for her vision. “There’s a compulsion that’s satiated only through consuming Kahlo’s agony,” Garcia writes. But it’s also true that we cannot reasonably separate her story from her work. It’s just that there is so more to the story than suffering, all of it woven into the texts of her paintings. Kahlo’s mythology, or “inspirational personal brand,” ties together her commitments to Marxism and Mexico, indigenous culture, and native spirituality.

Like all self-mythologizing before her, she folded her personal story into that of her nation. And unlike European surrealists, who “used dreamlike images to explore the unconscious mind, Kahlo used them to represent her physical body and life experiences.” The experience of disability was no less a part of her ecology than mortality, symbolic landscapes, floral tapestries, animals, and the physically anguished experiences of love and loss.

Generous approaches to Kahlo’s work, and this short overview is one of them, implicitly recognize that there is no need to separate the life from the work, to the extent that the artist saw no reason to do so. But also, there is no need to isolate one narrative theme, whether intense physical or emotional suffering, from themes of self-transformation and transfiguration or experiments in re-creating personal identity as a political act.

Who was Janus from whom he was named January?

Standard

Though, it is almost Summertime but let’s have a look at the history of the month named; January 😉 Have a nice Sunday ❤

Who was Janus from whom he was named January?

By :https://searchingthemeaningoflife.wordpress.com/author/searchingthemeaningoflife/

Janus is considered god of the Romans, but there are some who say that Janus was a stranger from Thessaly who had been exiled in Rome, where they say, that Kamiesis welcomed him and shared his kingdom with him. Janus then built a town on the hill, named Janiculum from the name of the goddess!…

Bust of the Roman god Janus at the Vatican Museum. January, January, or Calandar, or the Calandar (Pontian), is the first month of the year in the Gregorian Calendar and has 31 days.

The first day of the month, which is the first day of the year, is known as New Year’s Eve.

As everyone knows, Janus is one of the most ancient gods of the Roman pantheon. They stand him with two faces looking opposite, one front and the other back. These myths are exclusively Roman and are connected with the city authorities.According to some mythologists, Janus was a native of Rome, where he once reigned with Cameses, a mythical king whose only name we know. According to others, Janus was a foreigner who came from Thessaly and had been exiled in Rome, where they say, that Kamiesis welcomed him and shared his kingdom with him. Janus then built a town on the hill, which was named Janiculum by the name of the god. When he came to Italy with his wife, called Kamisis or Kamassinis, he had children, and especially the Tiber, a surname of the Tiber River. Later, after the death of Kamissi, Janus reigned alone in Latium, and when Saturnus, chased from Greece by his son Jupiter, arrived there, he hosted him (see Saturnus and Jupiter).In the reign of Janus, they attribute the usual characteristics of the Golden Age, the honesty of people, plenty of goods, stable peace, etc. They say that Janus invented the use of ships to come from Thessaly to Italy, as well as the coin. Indeed, the most ancient Roman bronze coins had on their front the image of Janus, while on the back of a ship’s bow. They also say that Janus deposed the first inhabitants of Lazio, the Aborigines (but this fact is attributed to Saturnos). Prior to this, the Aborigines lived in a miserable way and did not know either the cities or the laws or the cultivation of the land. Janus taught them all that.When Janus died, they deified him. His mythical personality is linked to other myths that have no apparent relationship with the past. They are particularly attributed to him by a miracle, which saved Rome from its capture by the Savines. At the time when Romulus and his companions kidnapped the Sabine women, Titus and the Savages attacked the new city. One night, therefore, Tarpius, the daughter of Capilla’s guardian, delivered the Acropolis to the Savines. They climbed up the Capitol Hill and were ready to overthrow the city’s defenders when Janus set off a fountain of hot water in front of the attackers, scaring them and letting them flee. In memory of this miracle, they decided in time of war to always leave the gate of the temple of Janus open, so that God can at any time help the Romans. They closed it only when peace reigned in the Roman Empire.They also believed that Janus had married Nymph Jcturna, whose sanctuary and source were near the temple of Janus in the Roman Agora. Together we did, say, a son, the god Fons or Fontus, who was the god of the springs. Seneca in his satirical poem about the transformation of Emperor Claudius into a zucchini (the Apolococity) tells Janus, a skilful orator, because he had the experience of buying, and experienced in his art, to look back and forth (that is, all their views), he advocated Claudius. But it is obviously a literary and ironic narrative ornament about the personality of a god, who did not take him any more seriously.

Who’s January

January is the first month of the Gregorian calendar. It was named after the god of the Romans, Janus. In January, Nomas Pompilios added the eleventh place to Romulus, which until then was ten months old. January has often changed its name, in honour of various emperors or members of the imperial family, even the goddess Hera. Initially, January counted 29 days, but later, with Julius Caesar’s calendar reform, two additional days were added.In January – as the Wikipedia has written – our people have given us names such as January because they bear the grazes and Meso Chimonas because it is the middle of the winter months, as the saying goes “as to Ai-Gianni, tiger, is the winter scream. ” It is also the moon with the brightest moon: “On January the moon looks like an hour or so.” It is also called Canto because during its duration the cats are mated, and the Great Month or the Transylvanian Month or Megalomnassas because it is the first month of the year and in contrast to February, which is “lame” (Koutsoflevaros). Oialkyon days have also given him the name “lax”, but he is also known as the “creeper”: “January moon cries, the moon is not looking”. Other names: Genolaitos (because this month they give birth to the herds), Kriaritsi because he is the most “cranky”.

BIBLIOGRAPHY:

Baron, De ling. lat. 5, 156, 7, 26 and 27. Macro., Saturn. I, 7, 19. 1, 9 et seq. Cell, Met. 14, 785 et seq. / Fasti 1, 63-294. Virg., Ain. 7, 180. 7, 610. 8, 357. 12, 198. Plut., Rev. El., 41, Ser., Comment. virg., Ain. 8.319. August. 7, 4. Solo 2, 5 et seq. Lydos 4, 2. cf. P. Grimal, “Janus and the origins of Rome”, Lcilves d’Humanite, 4th Holland, Janus and the Bridge, Am. Acad, in Rome, 1961.

source: https://www.sakketosaggelos.gr/

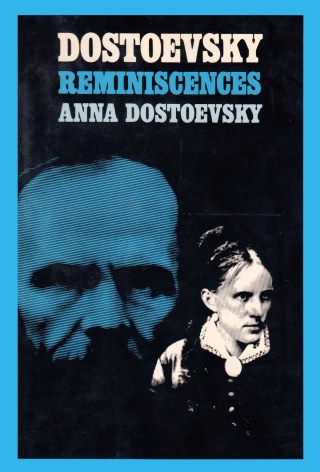

Anna Dostoyevskaya on the Secret to a Happy Marriage: Wisdom from One of History’s Truest and Most Beautiful Loves

StandardOr; I believe every Artists: Male or Female, need a Guardian Angel 😉

a happy end? I couldn’t imagine in the life of the great genius; Dostoyevsky, as I almost have grown up with his works (among the others 😉 ) I felt that he was, almost in his life, trying to focus the dark side of the human being;

“Happy? But I haven’t had any happiness yet. At least, not the kind of happiness I always dreamed of. I am still waiting for it.”

For example; when I read the Charles Dickens works, I got to know his abilities and his observation on the humans, that is genial knowledge over their soul but he was not so pointing on the dark side of us as Dostoyevsky tried to explore. I have learned a lot about my dark side as I read his book

Here I have the presence of light side, which it happens in his true life, and of course with the help of a wonderful woman “what else” who understood him better than any others. I knew just a few great artists who were so lucky to find their Guardian Angel; among Charles Dickens, my father was also so lucky; a pity that he had noticed it deeply at his last night on this Earth and how I wish if my brother could be so as well… what a pity!

Anyway, let’s read this wonderful story with the stunnishing happy end. 🙂

https://www.brainpickings.org/2016/02/15/anna-dostoyevsky-reminiscences-marriage/

via https://www.brainpickings.org/

In the summer of 1865, just after he began writing Crime and Punishment, the greatest novelist of all time hit rock bottom. Recently widowed and bedevilled by epilepsy, Fyodor Dostoyevsky (November 11, 1821–February 9, 1881) had cornered himself into an impossible situation. After his elder brother died, Dostoyevsky, already deeply in debt on account of his gambling addiction, had taken upon himself the debts of his brother’s magazine. Creditors soon came knocking on his door, threatening to send him to debtors’ prison. (A decade earlier, he had narrowly escaped the death penalty for reading banned books and was instead exiled, sentenced to four years at a Siberian labour camp — so the prospect of being imprisoned was unbearably terrifying to him.) In a fit of despair, he agreed to sell the rights to an edition of his collected works to his publisher, a man named Fyodor Stellovsky, for the sum of his debt — 3,000 rubles, or around $80,000 in today’s money. As part of the deal, he would also have to produce a new novel of at least 175 pages by November 13 of the following year. If he failed to meet the deadline, he would lose all rights to his work, which would be transferred to Stellovsky for perpetuity.

Only after signing the contract did Dostoevsky find out that it was his publisher, a cunning exploiter who often took advantage of artists down on their luck, who had purchased the promissory notes of his brother’s debt for next to nothing, using two intermediaries to bully Dostoyevsky into paying the full amount. Enraged but without recourse, he set out to fulfil his contract. But he was so consumed with finishing Crime and Punishment that he spent most of 1866 working on it instead of writing The Gambler, the novel he had promised Stellovsky. When October rolled around, Dostoyevsky languished at the prospect of writing an entire novel in four weeks.

Portrait of Fyodor Dostoyevsky by Vasily Perov, 1871

His friends, concerned for his well-being, proposed a sort of crowdsourcing scheme — Dostoyevsky would come up with a plot, they would each write a portion of the story, and he would then only have to smooth over the final product. But, a resolute idealist even at his lowest low, Dostoyevsky thought it dishonourable to put his name on someone else’s work and refused.

There was only one thing to do — write the novel, and write it fast.

On October 15, he called up a friend who taught stenography, seeking to hire his best pupil. Without hesitation, the professor recommended a young woman named Anna Grigoryevna Snitkina. (Stenography, in that era, was a radical innovation and its mastery was so technically demanding that of the 150 students who had enrolled in Anna’s program, 125 had dropped out within a month.)

Twenty-year-old Anna, who had taken up stenography shortly after graduating from high school hoping to become financially independent by her own labor, was thrilled by the offer — Dostoyevsky was her recently deceased father’s favorite author, and she had grown up reading his tales. The thought of not only meeting him but helping him with his work filled her with joy.

The following day, she presented herself at Dostoyevsky’s house at eleven-thirty, “no earlier and no later,” as Dostoyevsky had instructed — a favorite expression of his, bespeaking his stringency. Distracted and irritable, he asked her a series of questions about her training. Although she answered each of them seriously and almost dryly, so as to appear maximally businesslike, he somehow softened over the course of the conversation. By the early afternoon, they had begun their collaboration on the novel — he, dictating; she, writing in stenographic shorthand, then transcribing at home at night.

For the next twenty-five days, Anna came to Dostoyevsky’s house at noon and stayed until four. Their dictating sessions were punctuated by short breaks for tea and conversation. With each day, he grew kinder and warmer toward her, and eventually came to address her by his favorite term of endearment, “golubchik” — Russian for “little dove.” He cherished her seriousness, her extraordinary powers of sympathy, how her luminous spirit dissipated even his darkest moods and lifted him out of his obsessive thoughts. She was touched by his kindness, his respect for her, how he took a genuine interest in her opinions and treated her like a collaborator rather than hired help. But neither of them was aware that this deep mutual affection and appreciation was the seed of a legendary love.

In her altogether spectacular memoir of marriage, Dostoevsky Reminiscences(public library), Anna recounts a prescient exchange that took place during one of their tea breaks:

Each day, chatting with me like a friend, he would lay bare some unhappy scene from his past. I could not help being deeply touched at his accounts of the difficulties from which he had never extricated himself, and indeed could not.

[…]

Fyodor Mikhailovich always spoke about his financial straits with great good nature. His stories, however, were so mournful that on one occasion I couldn’t restrain myself from asking, “Why is it, Fyodor Mikhailovich, that you remember only the unhappy times? Tell me instead about how you were happy.”

“Happy? But I haven’t had any happiness yet. At least, not the kind of happiness I always dreamed of. I am still waiting for it.”

Little did either of them know that he was in the presence of that happiness at that very moment. In fact, Anna, in her characteristic impulse for dispelling the darkness with light, advised him to marry again and seek happiness in family. She recounts the conversation:

“So you think I can marry again?” he asked. “That someone might consent to become my wife? What kind of wife shall I choose then — an intelligent one or a kind one?”

“An intelligent one, of course.”

“Well, no… if I have the choice, I’ll pick a kind one, so that she’ll take pity on me and love me.”

While we were on the theme of marriage, he asked me why I didn’t marry myself. I answered that I had two suitors, both splendid people and that I respected them both very much but did not love them — and that I wanted to marry for love.

“For love, without fail,” he seconded me heartily. “Respect alone isn’t enough for a happy marriage!”

Their last dictation took place on November 10. With Anna’s instrumental help, Dostoyevsky had accomplished the miraculous — he had finished an entire novel in twenty-six days. He shook her hand, paid her the 50 rubles they had agreed on — about $1,500 in today’s money — and thanked her warmly.

The following day, Dostoyevsky’s forty-fifth birthday, he decided to mark the dual occasion by giving a celebratory dinner at a restaurant. He invited Anna. She had never dined at a restaurant and was so nervous that she almost didn’t go — but she did, and Dostoyevsky spent the evening showering her with kindnesses.

But when the elation of the accomplishment wore off, he suddenly realized that his collaboration with Anna had become the light of his life and was devastated by the prospect of never seeing her again. Anna, too, found herself sullen and joyless, her typical buoyancy weighed down by an acute absence. She recounts:

I had grown so accustomed to that merry rush to work, the joyful meetings and the lively conversations with Dostoyevsky, that they had become a necessity to me. All my old activities had lost their interest and seemed empty and futile.

Unable to imagine his life without her, Dostoyevsky asked Anna if she would help him finish Crime and Punishment. On November 20, exactly ten days after the end of their first project, he invited her to his house and greeted her in an unusually excited state. They walked to his study, where he proceeded to propose marriage in the most wonderful and touching way.

Dostoyevsky told Anna that he would like her opinion on a new novel he was writing. But as soon as he began telling her the plot, it became apparent that his protagonist was a very thinly veiled version of himself, or rather of him as he saw himself — a troubled artist of the same age as he, having survived a harsh childhood and many losses, plagued by an incurable disease, a man “gloomy, suspicious; possessed of a tender heart … but incapable of expressing his feelings; an artist and a talented one, perhaps, but a failure who had not once in his life succeeded in embodying his ideas in the forms he dreamed of, and who never ceased to torment himself over that fact.” But the protagonist’s greatest torment was that he had fallen desperately in love with a young woman — a character named Anya, removed from reality by a single letter — of whom he felt unworthy; a gentle, gracious, wise, and vivacious girl whom he feared he had nothing to offer.

Only then did it dawn on Anna that Dostoyevsky had fallen in love with her and that he was so terrified of her rejection that he had to feel out her receptivity from behind the guise of fiction.

Is it plausible, Dostoyevsky asked her, that the alleged novel’s heroine would fall in love with its flawed hero? She recounts the words of literature’s greatest psychological writer:

“What could this elderly, sick, debt-ridden man give a young, alive, exuberant girl? Wouldn’t her love for him involve a terrible sacrifice on her part? And afterwards, wouldn’t she bitterly regret uniting her life with his? And in general, would it be possible for a young girl so different in age and personality to fall in love with my artist? Wouldn’t that be psychologically false? That is what I wanted to ask your opinion about, Anna Grigoryevna.”

“But why would it be impossible? For if, as you say, your Anya isn’t merely an empty flirt and has a kind, responsive heart, why couldn’t she fall in love with your artist? What if he is poor and sick? Where’s the sacrifice on her part, anyway? If she really loves him, she’ll be happy, too, and she’ll never have to regret anything!”

I spoke with some heat. Fyodor Mikhailovich looked at me in excitement. “And you seriously believe she could love him genuinely, and for the rest of her life?”

He fell silent, as if hesitating. “Put yourself in her place for a moment,” he said in a trembling voice. “Imagine that this artist — is me; that I have confessed my love to you and asked you to be my wife. Tell me, what would you answer?”

His face revealed such deep embarrassment, such inner torment, that I understood at long last that this was not a conversation about literature; that if I gave him an evasive answer I would deal a deathblow to his self-esteem and pride. I looked at his troubled face, which had become so dear to me, and said, “I would answer that I love you and will love you all my life.”

I won’t try to convey the words full of tenderness and love that he said to me then; they are sacred to me. I was stunned, almost crushed by the immensity of my happiness and for a long time I couldn’t believe it.

Fyodor and Anna were married on February 15, 1867, and remained besotted with one another until Dostoyevsky’s death fourteen years later. Although they suffered financial hardship and tremendous tragedy, including the death of two of their children, they buoyed each other with love. Anna took it upon herself to lift the family out of debt by making her husband Russia’s first self-published author. She studied the book market meticulously, researched vendors, masterminded distribution plans, and turned Dostoyevsky into a national brand. Today, many consider her Russia’s first true businesswoman. But beneath her business acumen was the same tender, enormous heart that had made loving room within itself for a brilliant man with all of his demons.

Anna Dostoyevskaya by Laura Callaghan from The Who, the What, and the When

In the afterword to her memoir, Anna reflects on the secret to their deep and true marriage — one of the greatest loves in the history of creative culture:

Throughout my life it has always seemed a kind of mystery to me that my good husband not only loved and respected me as many husbands love and respect their wives, but almost worshipped me, as though I were some special being created just for him. And this was true not only at the beginning of our marriage but through all the remaining years of it, up to his very death. Whereas in reality I was not distinguished for my good looks, nor did I possess talent nor any special intellectual cultivation, and I had no more than a secondary education. And yet, despite all that, I earned the profound respect, almost the adoration of a man so creative and brilliant.

This enigma was cleared up for me somewhat when I read V.V. Rozanov’s note to a letter of Strakhov dated January 5, 1890, in his book Literary Exiles. Let me quote:

“No one, not even a ‘friend,’ can make us better. But it is a great happiness in life to meet a person of quite different construction, different bent, completely dissimilar views who, while always remaining himself and in no wise echoing us nor currying favor with us (as sometimes happens) and not trying to insinuate his soul (and an insincere soul at that!) into our psyche, into our muddle, into our tangle, would stand as a firm wall, as a check to our follies and our irrationalities, which every human being has. Friendship lies in contradiction and not in agreement! Verily, God granted me Strakhov as a teacher and my friendship with him, my feelings for him were ever a kind of firm wall on which I felt I could always lean, or rather rest. And it won’t let you fall, and it gives warmth.”

In truth, my husband and I were persons of “quite different construction, different bent, completely dissimilar views.” But we always remained ourselves, in no way echoing nor currying favor with one another, neither of us trying to meddle with the other’s soul, neither I with his psyche nor he with mine. And in this way my good husband and I, both of us, felt ourselves free in spirit.

Fyodor Mikhailovich, who reflected so much in so much solitude on the deepest problems of the human heart, doubtless prized my non-interference in his spiritual and intellectual life. And therefore he would sometimes say to me, “You are the only woman who ever understood me!” (That was what he valued above all.) He looked on me as a rock on which he felt he could lean, or rather rest. “And it won’t let you fall, and it gives warmth.”

It is this, I believe, which explains the astonishing trust my husband had in me and in all my acts, although nothing I ever did transcended the limits of the ordinary. It was these mutual attitudes which enabled both of us to live in the fourteen years of our married life in the greatest happiness possible for human beings on earth.

Complement the wholly enchanting Dostoevsky Reminiscences with Frida Kahlo’s touching remembrance of Diego Rivera, Jane Austen’s advice on love and marriage, and philosopher Erich Fromm on what is keeping us from mastering the art of loving, then revisit Dostoyevsky on why there are no bad people and the day he discovered the meaning of life in a dream.

Revisiting Joseph Campbell: The Power of Myth

StandardWhat do you really answer when your upspring ask you such questions as; why the fire is hot, or why the water is liquid or who is God?! My son had asked me such questions and I answered: you will learn and find by yourself! especially about God and religions; I told him that I have no religion but you are free to choose a one or even nothing. and I add that he must just rather read a lot and research deeply before making a decision.

For me, as I gave up all the religions, I did read hungrily about them and I came back in the Mythology which is the basis of all history, our history. even I read the old testament rather than the new one 😉 and it’s an amazing experience to feed our soul and our curiosity for solving the mystery; ~Where we’ve come from and What the …. are we doing here!~ 😀

Here I found an excellent article about this issue, it’s worthy to be read 🙂 have a great weekend everyone ❤ ❤

The mythological figures that have come down to us… are not only symptoms of the unconscious… but also controlled and intended statements of certain spiritual principles, which have remained as constant throughout the course of human history as the form and nervous structure of the human physique itself. Briefly formulated, the universal doctrine teaches that all the visible structures of the world – all things and beings – are the effects of a ubiquitous power out of which they rise, which supports and fills them during the period of their manifestation, and back into which they must ultimately dissolve.

Joseph Campbell

This article was published in New Dawn 144.

Perhaps myth first arose out of the answers parents give to their children’s questions. Many of these are unanswerable: Why is water wet? Why is fire hot? Where does everything come from? Who is God? Because people like to tell stories, it makes sense that parents would make up tales, far-fetched, elaborate, but sometimes beautiful, to satisfy this curiosity. The best of these would be passed down from generation to generation to form the body of worldwide myth.

Even so, this explanation does not tell us why myths are so powerful. Why should these stories have continued to be told for thousands of years? What meaning do they have and what role do they play in our lives?

The modern study of myth, and its close cousin, religion, began around the Enlightenment, when polymaths began to compile the traditions of non-Western peoples. They also tried to find common elements in these traditions. Most of their answers today look naïve and simplistic.

The mid-nineteenth-century British author Hargrave Jennings, for example, saw the origins of all the world’s religions in “phallicism,” a worship of the sexual force as well as of the sun and fire. J.G. Frazer, author of The Golden Bough and revered as one of the founders of the discipline of anthropology, said that myths, particularly of the death-and-resurrection variety, were merely recapitulations of the yearly vegetative cycle of growth, death, and renewal (a view known to, and derided by, Plutarch in the first century CE).

In the twentieth century, Émile Durkheim, one of the founding fathers of sociology, held that religion was nothing more than a primitive abstraction and internalisation of social forces: “Society in general, simply by its effect on men’s minds, undoubtedly has all that is required to arouse the sensation of the divine. A society is to its members what a god is to its faithful.” For the Swiss psychiatrist C.G. Jung, myth and religion expressed a deep layer of the mind that he called the collective unconscious.

All these views are true. There are many sexual motifs in myths and religion. Societies do unite themselves by means of common myths. There are underlying patterns of myth that seem universal, even among peoples who are far-flung and isolated. But these are only partial truths.

One of the most comprehensive – and best-known – discussions of myth appears in the writings of the American scholar Joseph Campbell (1904-87). Campbell’s view, expressed in books such as The Hero with a Thousand Faces and the Masks of Godseries, and in a famous series of televised interviews with the journalist Bill Moyers entitled The Power of Myth, is probably the most influential of all twentieth-century attempts. In many ways it is also the most wide-ranging and comprehensive.

Unlike his predecessors, who tended to see myth in one-dimensional terms (the product of social pressures, the expression of the collective unconscious, and so on), Campbell acknowledged that myth filled all of these functions. In Creative Mythology, the last volume of his Masks of God series, he writes:

The first function of a mythology is to reconcile waking consciousness to the mysterium tremendum et fascinans [the terrifying and fascinating mystery] of this universe as it is: the second being to render an interpretative total image of the same, as known to contemporary consciousness. Shakespeare’s definition of the function of his art, “to hold, as ’twere, the mirror up to nature,” is thus equally a definition of mythology. It is the revelation to waking consciousness of the powers of its own sustaining source.

A third function, however, is the enforcement of a moral order, the shaping of the individual to the requirements of his geographically and historically conditioned social group. [Emphasis here and in other quotes is in the original.]

These sentences summarise the mythological theories up to Campbell’s time, but they do not complete the picture. He goes on: “The fourth, and most vital, most critical function of a mythology… is to foster the centring and unfolding of the individual in integrity, in accord with d) himself (the microcosm), c) his culture (the mesocosm), b) the universe (macrocosm), and a) that awesome ultimate mystery which is both beyond and within himself and all things.” For Campbell, this fostering of individual potential is the most important function of myth. It is also the one to which he devotes the greatest part of his work.

The Hero

Following C.G. Jung, Campbell closely links dream and myth, emphasising how mythic themes appear in the dreams of ordinary people, even those who have never heard the original tales. Every man is a hero, living out these themes in the trials of daily life. “The latest incarnation of Oedipus, the continued romance of Beauty and the Beast, stand this afternoon on the corner of Forty-second Street and Fifth Avenue, waiting for the light to change.”

This quotation comes from The Hero with a Thousand Faces, published in 1949 and certainly the most influential of Campbell’s works. Its outline of the hero’s journey, drawing upon myths and lore from around the world, has inspired any number of books and films, including George Lucas’s Star Wars series. Broadly sketched, the journey proceeds thus: A person, usually an ordinary and undistinguished individual, is roused from the routine of his or her daily life by a call. This call may take the form of a dream, an animal, a god, or even a predicament: the journey in Dante’s Divine Comedy begins when the narrator, wakened from a stupor, finds himself in a dark wood from which he must escape.

The hero has free will, however, and may refuse the call. The punishment is an ossification of the self, sometimes symbolised by turning to stone: as Campbell writes, “Lot’s wife became a pillar of salt for looking back, when she had been summoned forth from her city by Jehovah.” In psychological terms this means fixation, which represents “an impotence to put off the infantile ego, with its sphere of emotional relationships.” We can see examples of this all around us: the eternal momma’s boy; the student who cannot leave university, taking degree after degree; the high-school football hero who dwells forever on a few moments of vanished glory on the field.

For those who accept the call, some kind of supernatural aid appears. In the Inferno, Dante, lost in the dark wood, is saved from wolves by a greyhound (a medieval symbol of Christ) and then meets with Vergil, for Dante’s age the greatest poet of classical antiquity. Thus this spirit guide can be masculine or feminine, animal or fairy. Among the American Indians of the Southwest one favourite figure is Spider Woman, and in many Christian myths the Virgin appears as this helper. In the hero’s journey of everyday life, the help may come in a subtler form: the appearance of a teacher or master, or even a book that serves as the perfect guide for this precise juncture.

Armed with this help, the hero is ready to cross the first threshold, the boundary between the known and the unknown, the everyday world and the underworld. The shadowy realms of this underworld are, Campbell tells us, “free fields of the projection of unconscious content.” They can be populated by demons, ogres, or other menacing creatures; the hero may also encounter alluring figures that will tempt him to destruction, like Circe or the Sirens in the Odyssey. If he fails to kill the ogre or master his desire for the voluptuous spectre, he is annihilated.

If he succeeds and goes past this threshold into what Campbell calls “the belly of the whale,” he is annihilated nonetheless. But here the annihilation is the very point of the endeavour. The image of the belly of the whale comes from the biblical book of Jonah, in which the protagonist flees his destiny as a prophet only to be swallowed by a “great fish,” in whose belly he stays for three days. During this time Jonah prays to the Lord and agrees to accept his mission: “I will pay that that I have vowed” (Jonah 2:9). The fish then vomits him up onto dry land.

Death & Resurrection

Campbell, like many commentators, underscores the death-and-resurrection motif in this part of the journey. The prophet dies to his old identity and is reborn with a new one. Quoting the esotericist Ananda K. Coomaraswamy, Campbell writes, “No creature can attain a higher grade of nature without ceasing to exist.” The same holds true for the most famous death-and-resurrection myth of them all – that of Christ. The Gospels stress that Christ is to go up to Jerusalem for the specific purpose of being crucified so that he may die and rise again. In this myth, Jerusalem, supposedly the spiritual pinnacle of humanity, is the underworld, and the ogres are the priests and scribes and Pilate. Christ is put to death in an excruciating and humiliating way, but after three days he rises again.

Before the hero can be resurrected, however, he usually has to undergo a series of trials in the underworld – tasks to be performed, some monster that must be overcome. In Christian myth, this corresponds to the “harrowing of hell,” in which Christ before his resurrection descends to the nether world and defeats Satan, liberating the righteous souls imprisoned there.

The hero does not always win this conflict, but either way he cannot lose. Even if he dies, he is restored to life in a new and glorified form.

Once the ordeals have been passed, the hero encounters the Goddess. This is not a desirable fate for those who are unprepared. Campbell recalls the Greek myth of Actaeon, a hunter who stumbles upon a glade where he sees the goddess Diana bathing naked. Because this is an accidental encounter, Actaeon must pay the price: Diana changes him into a stag, and he is torn to pieces by his own hounds.

This tale highlights two aspects of this part of the hero’s journey: the need for purification from his flaws (including his desires) and the dual nature of the Goddess. She is beautiful, she is infinitely tender, but she is also baleful. The hero cannot encounter one aspect without the other. Campbell recounts a vision of the nineteenth-century Hindu saint Ramakrishna, in which he sees a beautiful pregnant woman arising from the Ganges. She gives birth, but as soon as she does, she turns into a monster, seizes the baby in her jaws, crushes it, and chews it. The Goddess gives birth to all, but having given birth she will take it back again.

Once the hero faces and accepts this ambiguous and awesome nature of the Goddess, he marries her in a hieros gamos or sacred wedding, signifying the unification of the ambisexual nature that exists in every man and woman.

Having assimilated the force of the Goddess, the hero must undergo atonement with the father. Campbell expresses it thus:

The problem of the hero going to meet the father is to open his soul beyond terror to such a degree that he will be ripe to understand how the sickening and insane tragedies of this vast and ruthless cosmos are completely validated in the majesty of Being. The hero transcends life with its particular blind spot and for a moment rises to a glimpse of the source. He beholds the face of the father, understands – and the two are atoned.

As the quintessential example of this encounter, Campbell cites the book of Job. Job, a “simple and upright man, and fearing God, and avoiding evil,” is nonetheless plunged – for reasons he does not understand – into a maelstrom of suffering in which his fortune, his home, and his children are all annihilated. Most of this book consists of a poetic dialogue between Job, who insists upon his own righteousness, and his so-called comforters, who keep trying to persuade him that he must have done wrong to merit such treatment from the Lord. In the end the Lord himself appears to answer Job “out of the whirlwind,” demanding that he explain the inscrutable workings of the universe: “Where wast thou when I laid the foundations of the earth? declare, if thou hast understanding” (Job 38:4). Job cannot answer; in the end he can only say, “I repent in dust and ashes” (Job 42:6).

The book of Job remains to this day perhaps the most profound exploration of theodicy, the question of divine justice. But it is still an enigmatic and perplexing work. Jung, in his Answer to Job, saw the manifestation of the Lord as a kind of appeal to power – divine might makes right – but Campbell, as the passage above suggests, views this issue in a deeper and more nuanced way. There is no answer to this question in any conventional sense. The source of which Campbell speaks gives rise both to justice and injustice, as it says elsewhere in the Bible: “I form the light and create darkness: I make peace and create evil: I the Lord do all these things” (Isaiah 45:7). The Old Testament God is frequently mocked – as he is by Jung – for being childish and temperamental, but the Hebrew Bible is great in part because it acknowledges the unfathomable truth that good and evil both arise out of the One. Hence, too, the dual benign and maleficent nature of the Goddess.

Having faced and overcome these challenges, the aspirant becomes a master, with the power to move between the worlds of magic and of ordinary life. He then undergoes the process of return. And when he does return, he comes bearing the elixir – the boon that can bring healing to the world.

How the World Works

More could be said about the hero’s journey, as well as many other forms of myth that Campbell explores in his work. But it may be best to move on to some reflections. To begin with, Campbell is in his way a more profound, or at any rate a less ambivalent, thinker than his predecessor Jung. Jung, a conventionally trained psychiatrist, tended to stop short when he had to face the metaphysical implications of his thought. He was willing to say that his archetype of the Self – the psyche in a whole and integrated form – was an image of God, but he was reluctant to move on and say whether God did or did not exist outside of the psyche. Campbell is less equivocal:

The mythological figures that have come down to us… are not only symptoms of the unconscious… but also controlled and intended statements of certain spiritual principles, which have remained as constant throughout the course of human history as the form and nervous structure of the human physique itself. Briefly formulated, the universal doctrine teaches that all the visible structures of the world – all things and beings – are the effects of a ubiquitous power out of which they rise, which supports and fills them during the period of their manifestation, and back into which they must ultimately dissolve.

It would be hard to formulate a clearer or more concise summation of the spiritual teachings of humanity than this. Campbell is telling us these myths do not speak only to our psyches; they are also telling us how the world works.

This consideration brings up a perplexing issue. Because myth has cosmic implications, it must incorporate a vision beyond a person’s own narrow interests if it is to have any genuine meaning. It is easy to see how the hero’s journey corresponds to the trials of different phases of life. But if there is no more, then the journey speaks to the individual only. That is not enough. As the myths tell us, in the end the hero has to bring some boon to society. His journey has to have collective, if not universal, meaning and value.

While Campbell acknowledges this fact, at times it sounds as if he still prizes the individual vision above the collective.

Today, more fortunately, it is everywhere the collective mythology itself that is going to pieces, leaving even the non-individual (sauve qui peut!) to be a light unto himself. It is true that the madhouses are full; psychoanalysts, millionaires. Yet anyone sensible enough to have looked around somewhat outside his fallen church will have seen standing everywhere on the cleared, still clearing, world stage a company of mighty individuals: the great order of those who in the past found, and in the present too are finding, in themselves all the guidance needed.

But in fact Campbell is aware of the problem: “In the fateful, epoch-announcing words of Nietzsche’s Zarathustra: ‘Dead are all the gods’.” We are in a late phase of Christian civilisation, when the central myth of the faith has lost much of its power and many can no longer believe in it literally. While the passion of Christ mirrors the journey of the hero, it is not so easy to believe that it really happened as recorded. The Gospels offer many problems if taken as straight historical texts, and none of them (or any other surviving Christian text) was written by people who knew Jesus personally. The problem becomes still more acute when we turn to the myth of Genesis.

We are thus thrown back upon ourselves, as Campbell acknowledged: “In the absence of an effective general mythology, each of us has his private, unrecognised, rudimentary, yet secretly potent pantheon of dream.” The hero’s journey is not something that contemporary society can undergo collectively, as it did with the old mystery religions. Because of this isolation, “one does not know toward what one moves. One does not know by what one is propelled. The lines of communication between the conscious and unconscious zones of the human psyche have all been cut, and we are split in two.”

Campbell argues that we will need to unearth a new set of symbols to enact this reintegration. Moreover, “this is not a work that consciousness itself can achieve… The whole thing is being worked out on another level, through what is bound to be a long and very frightening process.”

Up to this point Campbell is right, but in a way he does not go far enough. The best way to see this is by taking another look at the word “myth.” Campbell does not use it as a term of disparagement: he does not, as a rule, say things like “The Genesis story is a mere myth” as opposed to something that is true. In fact “myth” does have this dual meaning. It goes back to the ancient Greeks, from whom we got the word and who frequently used it in a disparaging sense: “Myths [mythoi] deceive, embroidered by elaborate lies,” as the poet Pindar wrote in the early fifth century BCE.

This is a striking fact, and it reflects and influences our usage to this day. Whether employed by Jung or Campbell or anyone else, “myth” is never applied to anything that is believed to be factually true. When the Greeks and Romans started to think of their stories as myths, it meant they had ceased to believe in them. When we regard the Christian myth in the same way, it means the same thing. The modern rediscoverers of myth do not try to persuade us that it tells us how the world works physically, even if they regard it is true psychologically or metaphysically.

Thus the renovation of myth to which Campbell points cannot merely involve another set of symbolic images. We have catalogued the great mythic images of world culture, and we will probably not be able to add much that is new. Instead this symbolic renascence must also encompass a worldview in which we genuinely believe, much as a Christian of the year 1300 believed that the Earth really was the centre of the universe, surrounded by the spheres of the planets and stars. This was not a myth to that individual; it was the way things are.

Our myth today, though few dare call it such, is the scientific worldview. The Big Bang, the limitless expanses of galaxies, the evolution of species – this is how we believe things are in reality. Here we confront a problem. While this grandiose new scientific knowledge has furnished us with an unprecedented degree of technical mastery, it offers no sense of meaningful purpose. Quite the opposite: it seems remorselessly bent on proving the utter futility and triviality of human life. It tramples on any suggestion that anything could possibly exist that is not made of tiny particles moving about in some determinate yet curiously arbitrary pattern.

Hence the split between the conscious and the unconscious zones of the Western psyche. The conscious mind, educated in a precise but narrow framework, can accept this materialistic worldview; many people cannot accept anything else. But the unconscious revolts at the loss of meaning and will not stand for it. Common consequences include anomie and drug addiction as well as pathological greed and a mania for power.

This need for meaning and purpose, and for a connection to a reality that is larger than the sum total of material phenomena, indicates this reality exists. You would never feel thirst if there were no such thing as water. But at the same time we still feel the need to connect this higher reality with the universe that we know from sensory experience. We need a worldview that not only discovers distant galaxies but remind us of what Campbell calls the “ubiquitous power” out of which these galaxies arise. Such a worldview, if it can be found, will command the allegiance of humanity for a long time to come. Those who bring it will be the next generation of heroes. They may not have been born yet.

Sources

Joseph Campbell, The Hero with a Thousand Faces, 2d ed., Princeton University Press, 1968.

Joseph Campbell, The Masks of God: Creative Mythology, Viking, 1968.

Émile Durkheim, The Elementary Forms of Religious Life, Translated by Karen E. Fields, Free Press, 1995.

© New Dawn Magazine and the respective author.

Irish Folktale: Children of Lir

StandardVal is a writer of enchanted tales, folklore and magic. Once chased by Vampire Pumpkins!

The Children of Lir is an Irish Folktale, Lir was the lord of the sea. His first wife conceived four children with him. Later she died and Lir married his wife’s sister Aoife.

Unfortunately for his four children, Aoife was green with envy of them and concocted a magical spell transforming the 4 youngsters into 4 large white Swans. The children stayed as swans for 900 years until St. Patrick arrived in Ireland. According to Irish legend St. Patrick rang a Church bell and it miraculously broke the curse and returned the spellbound youngsters back to their former selves as children.

Source & Reference:

- MacKillop, James, ed. (2004), “Oidheadh Chlainne Lir”, A Dictionary of Celtic Mythology, doi:10.1093/acref/9780198609674.001.0001

- Featured Art: The Children of Lir(1914) by John Duncan

Mythology of The Unicorn

StandardVal is a writer of enchanted tales, folklore and magic. Once chased by Vampire Pumpkins!

Don’t you just love Unicorns? I do. I was fascinated with these eloquent, strong, equine creatures of antiquity since early childhood.

Below Photo of Chinese Qilin Statue in Summer Palace, Public Domain

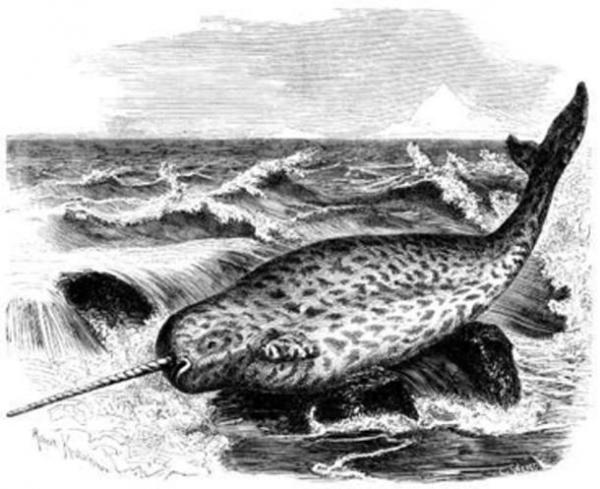

They may have originated from the Asian Unicorns such as the Qilin from China and the Kirin from Japan. Narwhals may be the original inspiration for the Unicorn, the tusk of the Narwhal was sold as the Unicorn horn in the past. Many Ancient Greek scholars wrote on the illustrious Unicorn such as Pliny the Younger, Ctesias and Strabo to list a few.

Below Illustration: Historical depiction of a narwhal from ‘Brehms Tierleben‘ (1864–1869) Public Domain.

Even the Bible in the Old Testament mentions the Unicorn

“God brought them out of Egypt; he hath as it were the strength of an unicorn.”—Numbers 23:22 (including several more passages.)

Unicorns may have also evolved from Elasmotherium that roamed Siberia 39,000 years…

View original post 439 more words

You must be logged in to post a comment.