Perfume has a rich history in human culture, such as ancient Persia, which dominated the perfume trade for decades. This civilization is known for inventing non-oil-based perfumes, and the Persian nobility valued fragrances highly, with kings having unique “signature scents” reserved exclusively for them. Ancient Persia had many perfume-making workshops where people experimented with various distillation processes and scents.

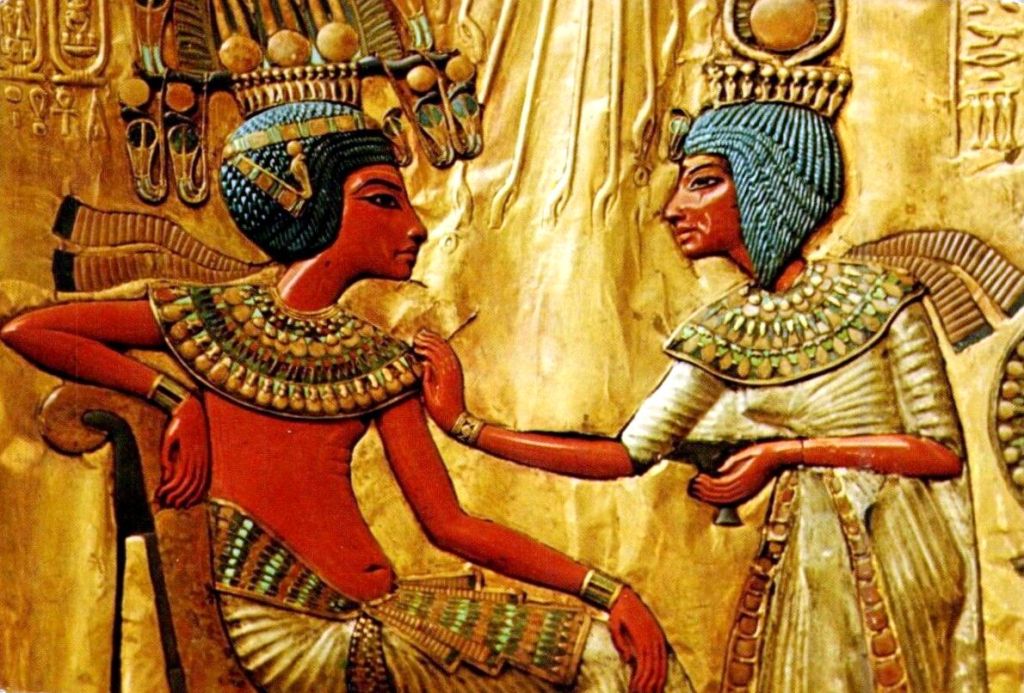

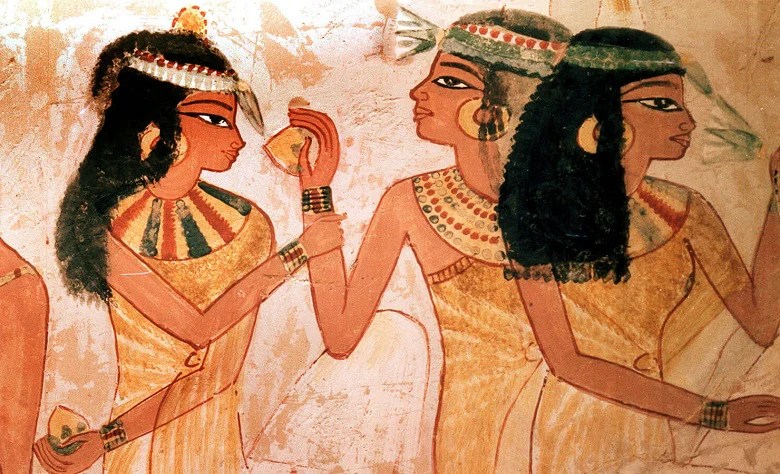

In Ancient Egypt, the elite highly valued perfume oils and fragrances. The god Nefertem, associated with perfume, is often depicted with water lilies, a key ingredient in ancient scents.

Perfumes were created by distilling natural ingredients in non-scented oils, resulting in fruity, woodsy, or floral aromas. Notable figures like Queen Hatshepsut and Queen Cleopatra enjoyed these fragrances, using them for baths and personal grooming. It is rumoured they took perfumes to their graves.

Here is the story of finding a tiny but precious perfume bottle from ancient Egypt, written by Marie Grillot, with heartfelt gratitude.🙏💖

An Amarna princess on a vase-shaped perfume bottle: Hes.

via égyptophile

travertine (Egyptian alabaster), carnelian, obsidian, gold, coloured glass inlays

New Kingdom – 18th Dynasty – reign of Akhenaten (1353 – 1336 BCE)

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York – accession number 40.2.4. (by acquisition from the Carter Estate in London in 1940) – museum photo

This delightful perfume bottle, in the form of a “Hes”( meaning “praise” or “favour) vase, is 10.8 cm high, 3 cm wide and has a diameter of 1.9 cm. According to some sources, it is made of calcite (Egyptian alabaster or travertine), with a decoration made of carnelian, obsidian, gold and coloured glass. In “Scepter of Egypt II”, William C. Hayes details its manufacturing technique thus: “The conical stopper was here cut in one piece with the pot itself. Since its tiny neck would have been too small to allow the insertion of a drilling tool, the bottle was made in two vertical halves, hollowed out and carefully joined with an orange resin glue”.

travertine (Egyptian alabaster), carnelian, obsidian, gold, coloured glass inlays

New Kingdom – 18th Dynasty – reign of Akhenaten (1353 – 1336 BCE)

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York – accession number 40.2.4. (by acquisition from the Carter Estate in London in 1940) – museum photo

Its charming appearance is enhanced by the presence, on one side, of a princess’s representation in inlays. Seen in profile, it reveals a naked, slim and youthful body. Her partially shaved skull displays on one side the “braid of childhood”; thick and black, it is thrown back. One leg is advanced, and she is in the apparent walking position. One arm hangs along the body, while the other displays a bent elbow and an outstretched hand, palm open. “The elegant gesture of the princess seems to signify a sign of greeting: standing on a lotus flower according to traditional symbolism, she embodies rebirth and rejuvenation”, analyzes Dorothea Arnold in “The Royal Women of Amarna”. Indeed, the ancient Egyptians considered the lotus as “the initial flower” and “the symbol of the birth of the divine star”.

For Egyptologist Valérie Angenot: “The gesture of the little princess, the hand outstretched in a cup, is stereotypical of the gestures of princesses since the time of Hatshepsut. It denotes the attitude of a child who wants to attract someone’s attention and address them by gently pulling their chin towards her. At Tell el-Amarna, the gesture is attested about fifteen times on the walls of private tombs, administrative monuments such as the king’s audience hall, steles, perhaps seal impressions, as well as on this vase. It exclusively features princesses, mostly to show that they interact or chat among themselves during long official ceremonies, which one imagines is tedious for young children. But we can also see them making this gesture in their interaction with their parents or even with the uraeus hanging from their foreheads. At Deir el-Bahari, Hatshepsut addresses the god Amon, her father, on whose knees she stands as a child. We must, therefore, imagine an elliptical interlocutor for this vase. Various reliefs show Akhenaten and Nefertiti performing a libation to the Aten with similar vases (but often adorned with a spout, 𝘯𝘦𝘮𝘴𝘦𝘵). Therefore, the ‘person’ to whom this little princess emerging from a solar lotus is addressing herself would be none other than the god Aton, whose honour the ritual would be simulated using this artificial vase. It is remarkable that we still find the same stereotypical gesture of the cupped hand sketched by one of the two Amarna ‘kings’ on the famous Berlin stele of Captain Pasi (ÄM 17813).”

travertine (Egyptian alabaster), carnelian, obsidian, gold, coloured glass inlays

New Kingdom – 18th Dynasty – reign of Akhenaten (1353 – 1336 BCE)

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York – accession number 40.2.4. (by acquisition from the Carter Estate in London in 1940) – museum photo

The details of its morphology, such as the elongation of the skull, the shape of the face, and the marked belly, attribute it to the Amarna period… William C. Hayes gives this sensitive description: “The naked figure of the young girl – which seems to come straight out of one of the scenes preserved in relief at Tell el-Amarna – is delicately carved in a thin sliver of carnelian, the back of which has been hollowed out to fit exactly the curved surface of the vase. The hair of the figure, topped with the characteristic heavy side lock, is a piece of polished obsidian or black glass beautifully worked and skillfully fitted. Spears and triangles of purple glass (imitation lapis lazuli) and polished carnelian have been joined together to form the lotus flower on which the figure stands, and at the base of the flower, a spot of sparkling yellow has been provided by a piece of thin gold plate.”

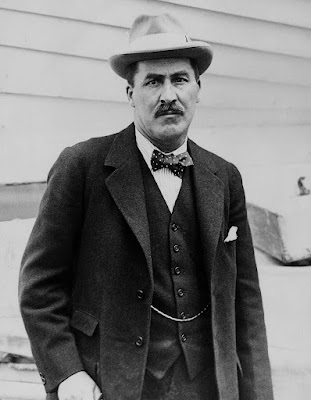

This precious artefact dates to the New Kingdom, the 18th Dynasty, the reign of Akhenaten (1353 – 1336 BC). It is in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, where it has been registered under the accession number 40.2.4, with the “ancient provenance”: “possibly Thebes.” As for its “recent provenance,” it is “speaking”: “Howard Carter Collection, acquired from the Carter estate in London in 1940.”

(London 9-5-1874 – 2-3-1939)

Draughtsman and Egyptologist, discoverer, in November 1922 with Lord Carnarvon, of the tomb of Tutankhamun

Howard Carter, painter and designer, Egyptologist, collector, and discoverer with Lord Carnarvon of the tomb of Tutankhamun in 1922, died in London on March 2, 1939. In his will (drawn up on July 14, 1931), he had designated his niece Phyllis Walker as heir to the majority of his assets, stipulating that, for all matters concerning the sale of Egyptian antiquities, she should refer to the executors he had appointed: Harry Burton and Bruce Ingram. The latter, noting in his apartment the presence of artefacts from the tomb of Tutankhamun, opted for restitution to Egypt. On March 22, 1940, Phyllis Walker wrote to Etienne Drioton, director of Egyptian antiquities, to organize this “return”. This is how around twenty artefacts will be returned, via diplomatic bag, to King Farouk… before joining the Tahrir Museum…

Draughtsman and Egyptologist, discoverer, in November 1922 with Lord Carnarvon, of the tomb of Tutankhamun

With his niece Phyllis Walker, who will be his primary heir

Returning to this point in “Howard Carter, The Path to Tutankhamun”, Thomas Garnet Henry James confides: “A further comment on this sensitive subject is that the antiquities in his possession at his death, after the extraction of the Tutankhamun objects, were valued by Messrs Spink at £1093. This was certainly a low estimate, as was often the case in estate matters, but it indicates the relatively modest nature of his private collection…”

Thus, in this inventory carried out on June 1, three months after the discoverer’s death, by the London art dealers Spink & Son of St James’s Street (“Spink list”), this bottle bears the number 55.

Of course, the question arises as to whether it is linked to the young pharaoh’s funerary treasure…

Thomas Garnet Henry James’s opinion is as follows: “It can be said that any fine small object dating from the 18th Dynasty which appeared in a private collection or on the market in the 1920s and 1930s was almost systematically attributed to the tomb of Tutankhamun”…

As for Marc Gabolde, he draws up, in his excellent “Tutankhamun”, published by Pygmalion in 2015, a list of “Objects possibly coming from the tomb of Tutankhamun and not found (somewhere else) in Egypt”. This calcite bottle in the shape of a libation vase (hs) appears there with the following information: “The quality of the work and the materials, as well as the date that can be assigned to the object thanks to the iconography of the inlaid figure, leave little doubt that it could come from the tomb of Tutankhamun. The figure of the princess is incompatible with the time of Amenhotep III, and the royal tomb of Amarna has not provided similar objects, especially in such a state of preservation”…

Sources:

Perfume bottle in the shape of a hes-vase inlaid with the figure of a princess https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/543992 William C. Hayes, Scepter of Egypt II: A Background for the Study of the Egyptian Antiquities in the Metropolitan Museum of Art: The Hyksos Period and the New Kingdom (1675-1080 B.C.), Cambridge, Mass.: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1959. p. 314; p. 317, fig. 199 https://archive.org/details/in.gov.ignca.28841 https://www.metmuseum.org/en/met-publications/the-scepter-of-egypt-vol-2-the-hyksos-period-and-the-new-kingdom-1675-1080-bc #115 Thomas Garnet Henry James, Howard Carter, The path to Tutankhamun, TPP, 1992 https://archive.org/stream/HowardCarterThePathToTutankhamunBySam/Howard+Carter+The+Path+to+Tutankhamun+By+Sam_djvu.txt Dorothea Arnold, The Royal Women of Amarna: Images of Beauty from Ancient Egypt, Metropolitan Museum of Art New York, 1996, fig. 115, p. 116. https://books.google.fr/books?id=sGLFwVkljQMC&pg=PR12&lpg=PR12&dq=Harkness+edward+queen+Tiye&source=bl&ots=MulVu6vNW S&sig=zL2tg-zHcQ2Ia-ra5NSPtbXaYtE&hl=fr&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwjl5ua_oY7KAhWCQxoKHX_qBXYQ6AEIMjAC#v=onepage&q=yellow&f=false Nicholas Reeves, Howard Carter’Collection of Egyptian and Classical antiquities, The Spink List, (Chief Of Seers: Egyptian Studies in Memory of Cyril Aldred), Editor: Kegan Paul, 1997 https://books.google.fr/books?id=K_Ill17K2wsC&pg=PA243&lpg=PA243&dq=ivory+figure+of+a+dog+(ear+chipped)&source=bl&ots=dsAnFliI3O&sig=PWT4Cg8cicNIiajywtVJsYZQkX0&hl=fr&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwiIgPiwsYngAhUpzoUKHRJxDn0Q6AEwB3oECAcQAQ#v =onepage&q=ivory%20figure%20of%20a%20dog%20(ear%20chipped)&f=false Isabelle Franco, Dictionary of Egyptian Mythology, Pygmalion, 1999

Nicholas Reeves, Tutankhamun, life, death and discovery of a pharaoh, Editions Errance, 2003

Marc Gabolde, Tutankhamun, Pygmalion, 2015

You must be logged in to post a comment.