This fascinating jewel is not only a designer piece but a symbol of birth and rebirth!

Here is another brilliant article by Marie Grillot about the secret of this magical lotus jewel, which will remain forever.

This pendant comes from the treasure of Princess Mérit (Mereret), whose tomb was found in March 1894 by Jacques de Morgan in the sector of the “northern pyramid” of Dahchour.

By Museo Egizio

Cloisonné gold pendant of a princess of Dahchour

Middle Kingdom – 12th Dynasty – Reigns of Sesostris III and Amenemhat III – 1878 – 1798 BC-AD

discovered in his tomb in Dahchour on March 6, 1894, during excavations carried out by Jacques de Morgan

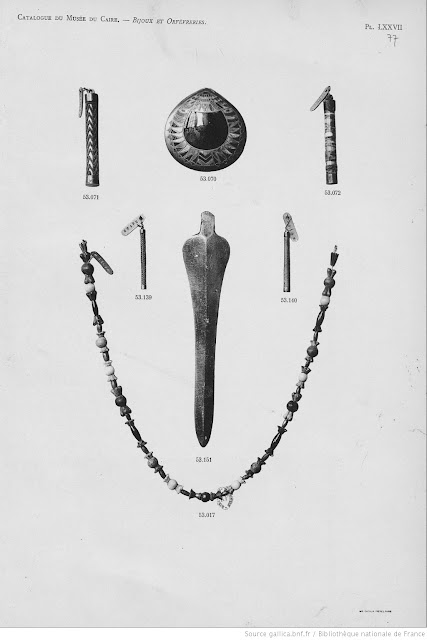

Egyptian Museum in Cairo – CG 53070 – JE 30877 – photo of the museum

via égyptophile

This lovely pendant is made of cloisonné gold, garnished with semi-precious stones. The brilliance that the gems reflect, their perfect execution, and their exceptional state of conservation make it difficult to believe that they are almost… 4000 years old!

It takes the shape of a “convex” shell, the upper part representing an open lotus flower. Its petals, pointing downwards, are made of a delicate and luminous cloisonné composed of turquoise, lapis lazuli and carnelian.

Middle Kingdom – 12th Dynasty – Reigns of Sesostris III and Amenemhat III – 1878 – 1798 BC-AD

discovered in his tomb in Dahchour on March 6, 1894, during excavations carried out by Jacques de Morgan

Egyptian Museum in Cairo – CG 53070 – JE 30877

published here in “Jewelry and goldsmiths. Booklet 3”, Émile Vernier

“Under this area, the main decoration develops. The middle is occupied by a carnelian of unusual dimensions: 0 m. 021 millimetres high and 0 m. 026 millimeters wide. Its general shape is close to a circle, part of which is cut by the upper area. All around the carnelian, a decoration is developed made, in the axis, of alternating cloisonné chevrons: lapis, carnelian and turquoise, and on each side, curved serrations of turquoise, leaving between them curvilinear triangles in carnelian followed by other small triangles of lapis, then approaching the upper area, alternating bands of lapis and turquoise and ending with an ellipse in turquoise having as its middle a small ellipse of lapis is framed by a fairly wide edge where the gold is bare. The reverse is made of a concave plate of plain gold, where we see a horizontal ring in the upper part, flat and vertically striated,” explains Emile Vernier (Jewelry and goldwork. Booklet 3).

Cyril Aldred’s interpretation follows: “The pendant… is inlaid with a motif inspired by the lotus flower from which is suspended a crown of stylized flower petals, ending in a pendant of three chevrons”.

As for Nigel Fletcher-Jones (“Ancient Egyptian Jewelry”), he specifies that “The pendant was originally suspended from a chain of gold beads to which twenty-six small oyster shells were soldered at regular intervals”.

Middle Kingdom – 12th Dynasty – Reigns of Sesostris III and Amenemhat III – 1878 – 1798 BC-AD

discovered in his tomb in Dahchour on March 6, 1894, during excavations carried out by Jacques de Morgan

Egyptian Museum in Cairo – CG 53070 – JE 30877 – photo of the museum

This jewel is loaded with symbols and “powers”… Thus, the oyster shell was, for a short period of the Middle Kingdom, an amulet which, according to Carol Andrews (Amulets of Ancient Egypt) “, gave health” and brought well-being to the person who wore it… As for the lotus, which is very present in Pharaonic iconography, it is not only the symbol of birth but also that of rebirth.

The stones used are also loaded with symbolism. In “The Gold of the Pharaohs”, Christiane Ziegler provides these details: “The ‘méfékat’ turquoise was extracted from Sinai where the pharaohs launched mining expeditions. Its luminous colour, evoking the growth of young shoots in spring, was synonymous with vitality and joy. Its presence in the funerary equipment undoubtedly gave the dead the joy of rebirth.” Carnelian, Héréset, “possessed the invigorating virtues of blood”. As for lapis lazuli, she explains to us: “in ancient myths, it constituted the beard and hair of the gods and had virtues comparable to those of turquoise”…

Pyramid of Amenemhat III in Dahchour

Photo by Jacques de Morgan published in “Excavations at Dahshur”, 1894

This pendant comes from the treasure of Princess Mérit (Mereret), whose tomb was found in March 1894 by Jacques de Morgan in the sector of the “northern pyramid” of Dahchour.

In his work “Excavations at Dahchour”, published the same year, he relates: “The underground necropolis that I had just opened was therefore not the tomb of the king, but rather the gallery of the princesses, one of the annexes of the tomb principal. Later, I discovered among the treasures the names of the princesses Hathor-Sat and Merit and the titles of a sixth royal daughter on the worm-eaten remains of a wooden box. Then he adds, “Meticulous examination of the floor of the galleries revealed on March 6 a cavity dug in the rock at the foot of sarcophagus C. The ground was loose,e and the worker’s foot sank into the middle of the moving debris. A few blows of the pickaxe revealed its treasures: gold and silver jewels and precious stones were there, piled up in the middle of the worm-eaten fragments of a box where they had once been kept. “

Middle Kingdom – 12th Dynasty – Reigns of Sesostris III and Amenemhat III – 1878 – 1798 BC-AD

discovered in his tomb in Dahchour on March 6, 1894, during excavations carried out by Jacques de Morgan

Egyptian Museum in Cairo – CG 53070 – JE 30877

published here in “Excavations at Dahshur” by Jacques de Morgan

Georges Legrain, who worked alongside him, was responsible for drawing up the first jewellery catalogue and faithfully reproducing drawings and watercolours. The large number of pieces to be presented will mean that this pendant will be described in a laconic manner: “Bivalve shell decorated with multicoloured stones on its convex part. The main design represents a lotus flower supporting an indefinite red object, from which herbs escape …”

Jacques de Morgan brandishing one of the pieces of Dahchour’s treasure (Princess Khnoumit’s tiara)

during its discovery in April 1894 in the funerary complex of Amenemhat II in Dashour

(drawing published in “L’Illustration” on May 11, 1895)

We can only subscribe to the words of Pierre Tallet in his work “Sesostris III and the end of the 12th Dynasty”: “One last area where the ending 12th dynasty seems to have particularly excelled is that of jewellery. The royal necropolises of this period thus delivered the first truly important collection of Egyptian jewellery, for the most part, intended for women in the pharaoh’s entourage: jewellery and toiletries from Sat-Hathor-Iounet to El-Lahoun, Mereret… These different lots of Precious objects, where gold, silver and various fine stones such as lapis lazuli, turquoise, amethyst and carnelian abound, give an idea of the splendour in which the royal family lived.

This pendant was registered in the Journal of Entries of the Cairo Museum under the reference JE 30877 and in the General Catalogue CG 53070.

Marie Grillot

Sources:

Excavations at Dahchour, Jacques de Morgan, Berthelot, M. (Marcellin), Legrain, Georges Albert, 1865-1917; Jquier, Gustave, 1868-1946; Loret, Victor, 1859-1946; Fouquet, Daniel https://archive.org/details/fouillesdahcho01morg/page/n213/mode/2up Dahchour excavations: 1894-1895, Jacques de Morgan, Wien 1903, http://digi.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/diglit/morgan1903/0049 Jewellery and goldsmiths. Booklet 3, Number 52640-53171, by Mr. Émile Vernier http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k57740426/f96.item.r=52859.texteImage Summary list, booklet published in 1894 by M. de Morgan; Excavations at Dahchour, II; Morgan’s catalogue, 1897 by Morgan Jacques. Letter on the latest discoveries in Egypt. In: Reports of the sessions of the Academy of Inscriptions and Belles-Lettres, 38th year, N. 3, 1894. pp. 169-177; https://doi.org/10.3406/crai.1894.70401 https://www.persee.fr/doc/crai_0065-0536_1894_num_38_3_70401 Jewellery and goldsmiths. Booklet 3, Number 52640-53171, by Mr. Émile Vernier http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k57740426/f96.item.r=52859.texteImage The gold of the pharaohs – 2500 years of goldsmithing in ancient Egypt, Catalogue of the summer 2018 exhibition at the Grimaldi Forum in Monaco, Christiane Ziegler Jewels of the Pharaohs, Cyril Aldred, ed Thames & Hudson Ltd. London, 1978 Ancient Egyptian Jewelry: 50 Masterpieces of Art and Design, 2019, Fletcher-Jones, N, The American University in Cairo Press Ancient Egyptian Jewelry, Carol Andrews, Harry N. Abrams, INC., Publishers, 1991 Amulets Of Ancient Egypt, Carol Andrews, published for Trustees of the British Museum by British Museum Press https://archive.org/details/AmuletsOfAncientEgypt_201707 Treasures of Egypt – The wonders of the Egyptian Museum in Cairo, Francesco Tiradritti

Posted December 21 2021, by Marie Grillot

Labels: CG 53070 – JE 30877 Dachour Dashour de Morgan expo Ramsès II 2023 fouilles 1894 Jacques de Morgan la villette Mereret Merit Mérit or clloisonnée pendeentif

You must be logged in to post a comment.