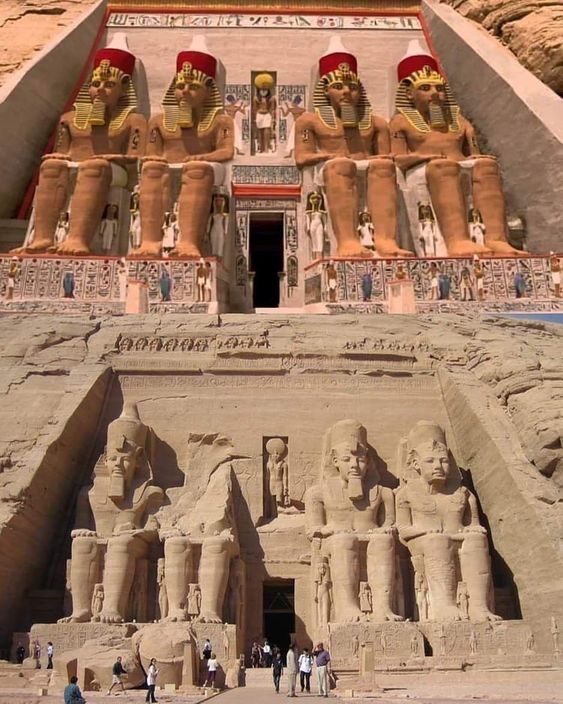

In ancient Egypt, there were eleven pharaohs named Ramesses, one of whom was Ramses II, known as The Great. This title likely stemmed from his lengthy reign of 66 years and his famous association with Moses.

Photo by konde on flickr

|Detail from a relief. King Ramses II, among the gods, the relief comes from the small temple built by King Ramses II at Abydos. In the relief, Ramesses II is crowned by the goddess Nekhbet in the form of a vulture. And Ramses II is introduced with the gods. 19th Dynasty, Abydos B 10, B 11, B 12, B 13, B 14. Louvre Museum

Perhaps his secrets are boundless and still awaiting discovery. We gain a deeper understanding of these mysteries thanks to Frédéric Payraudeau and the insightful interview by the brilliant Marie Grillot.🙏💖

“Image credit at the top: A relief of Ramesses II from Memphis showing him capturing enemies: a Nubian, a Libyan and a Syrian, c. 1250 BC. Cairo Museum. (CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikipedia)”

Frédéric Payraudeau’s research reveals the existence of a granite sarcophagus of Ramesses II

via égyptophile

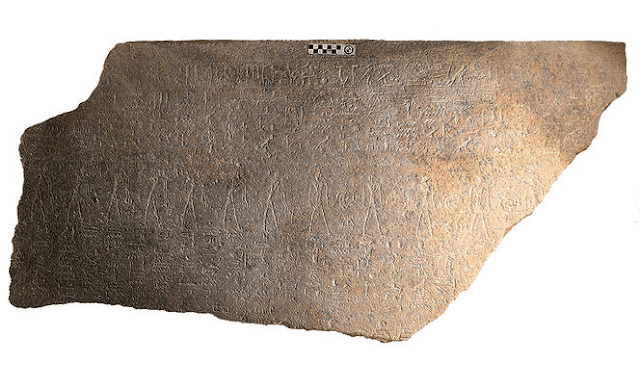

this fragment of granite sarcophagus (in the centre – photo Kévin Cahail) was found in Abydos in 2009

as belonging to the original sarcophagus of Ramses II

on the right, a relief of a monument representing Ramses II located in Tanis

Of the funerary equipment of Ramses II, we are incredibly familiar with the anthropoid coffin made of cedar wood (Cairo Museum – JE 26214 – CG 61020), found in the Royal Cachette of Deir el-Bahari (DB 320) in 1871/1881 which, although having preserved its mummy, did not belong to him… It is less well known that hundreds of fragments of his calcite sarcophagus, smashed by looters, were found in his tomb in the Valley of the Kings (KV 7) by Christian Leblanc, revealing that he had benefited from the same type of sarcophagus as his father Sety I (exhibited at Sir John Soane’s Museum in London)… In recent months, thanks to the acuity of the research carried out by the Egyptologist Frédéric Payraudeau, we have discovered that the man who reigned over the Dual Country for 66 years possessed a granite sarcophagus in which the calcite one must have been placed. A new “approach” to the royal burials of the early Ramesside era is emerging as a new page of post-Rameside history, with its reuses, can be read in palimpsests…

Found in the Royal Cachette of Deir el-Bahari (DB 320), discovered in 1871 by the Abd el-Rassoul Family

and “rediscovered” in 1881 by the Antiquities Department – registered at the Egyptian Museum in Cairo – JE 26214

MG-EA: Frédéric Payraudeau, Egyptologists produce numerous scientific studies each year. How did you become interested in the one concerning a fragment of a granite sarcophagus, 1.70 m long and 8 cm thick, discovered in 2009 by the Egyptian archaeologist Ayman Damrani in the paving of a Coptic monastery in Abydos?

FP: It turns out that this large sarcophagus fragment was reused by the high priest of Amun Menkheperre of the 21st Dynasty, a period that has been at the heart of my research on the Third Intermediate Period for a long time. So, I naturally became interested in the article publishing the monument in 2017. It was in itself a great discovery, indicating in particular that the tomb of the high priest must be in Abydos.

Found in Abydos in 2009, as belonging to the original sarcophagus of Ramses II – Photo Kévin Cahail

MG-EA: Was it the type of hieroglyphic inscriptions, the presence of a cartouche, or the quality of the material that caught your attention? And, since you had never had this fragment in your hands, what elements could you work on? What was your study approach?

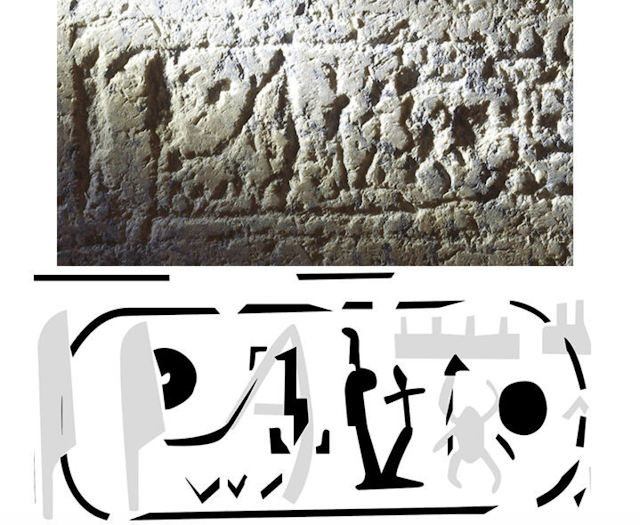

FP: The piece was fascinating and of such quality that it necessarily belonged to the elite, as my Egyptian and American colleagues had seen, but I was not satisfied with the reading of the texts. It must be said that engraving on granite when poorly preserved, is very difficult to understand when there is a superposition of texts. I worked first on the photos of the article itself, then, to eliminate any uncertainty, on working photographs that Kevin Cahail very kindly sent me. The engraving of the cartouche first was then sure, and the reading of the coronation name of Ramses II followed.

Drawing of the cartouche of Ramses II overprinted with the name of the high priest Menkheperrê (by Frédéric Payraudeau)

MG-EA: This sarcophagus was reused by the high priest Menkheperrê during the 21st dynasty. Is his “biography” well documented?

FP: The high priest Menkheperrê is a well-known character. In the second half of the 11th century BC, he was the pontiff of Amon and general-in-chief of Upper Egypt for almost half a century under the reign of his brother Psusennes, the pharaoh in Tanis. In Karnak, he notably restored the temple enclosure.

MG-EA: At the end of the Ramesside period marked by the pillaging of the tombs of the Valley of the Kings, the high priests of Amun restored and then sheltered the royal mummies in hiding places to protect them… Can we imagine that, a century later, their successors came to “help themselves” to the funerary furniture that remained “in situ”? Why and how did they come to reuse certain sarcophagi, even if it was far from their burial place (and in Tanis, do you know anything about it)?

It is much worse than that: the high priests organized part of the looting of the necropolis. Thefts by bands of looters from the ordinary people were a pretext for intervening at the very end of the reign of Ramses XI in the Valley of the Kings. The desire to protect the royal mummies went hand in hand with appropriating the treasures that had not yet been looted. The workers of Deir el-Medina, whose ancestral role was to dig and decorate the royal tombs, saw their activities reoriented towards exploiting the riches of the Valley of the Kings. We still have traces of this just before the pontificate of Menkheperrê, under his other brother Masaharta, who sent a team to the Valley “to look for gold for the high priest”. By the time Menkheperre’s teams came to recover the sarcophagus of Ramesses II and one of those of Merenptah for himself and Psusennes, these two tombs had already been emptied mainly by the previous high priests. The appropriation of these prestigious objects, whose names of the first owners were not entirely erased, was a way of connecting with this prestigious past. This craze for the Ramesside period is also visible in Tanis, where the city was built, at the same time, using materials taken from the abandoned Piramesses.

reused for Psusennes I – 21st dynasty – found in his tomb in Tanis (NRT III) by Pierre Montet in February 1940 – Egyptian Museum, Cairo – JE 87297.2

MG-EA: Ramses II himself had “reused” many statues, engraving his name and correcting the features of his predecessors… His sarcophagus, taken from the “gold chamber” of his tomb, was thus “reused” 200 years after he died for a high priest… And then a fragment was found in a Coptic place of worship: history repeats itself, or even perpetuates itself?

FP: Ancient Egypt extensively practised reuse, not only for economic but often also for cultural or political reasons. Should we recall that most of Tutankhamun’s treasures, including the famous golden mask, previously belonged to the queen who preceded him on the throne? According to their module, the columns in the eastern sector of Tanis date from the Old Kingdom. They were reused by Ramses II in a sanctuary of Piramses, then transported to Tanis and re-engraved under Osorkon II before being moved to where we admire them today in the Late Period or after. So, yes, we would be wrong to think that ancient objects only had one life.

Marie Grillot performed and released the interview for Egypt-news and Egyptophile.

Frédéric Payraudeau is an Egyptologist, lecturer at Sorbonne University, director of the French Mission of the Excavations of Tanis (MFFT)* and vice-president of the French Society of Egyptology. He is the author of numerous works, including “L’Egypte et la vallée du Nil. Tome 3: Les époques tardives …”, published by PUF

We sincerely thank him for agreeing to dedicate this interview to us despite his schedule and the start of the new mission in Tanis.

- To learn more about the MFFT:

- FB page: https://www.facebook.com/profile.php?id=100057098724072 Dedicated space on the EPHE website: https://www.ephe.psl.eu/recherche-innovation/recherche-en-reseau/mission-francaise-des-fouilles-de-tanis-mfft

- Published 5 weeks ago by Marie Grillot

You must be logged in to post a comment.