“When he arose, he took the young Child and His mother by night and departed for Egypt, and was there until the death of Herod the Great, that it might be fulfilled which was spoken by the Lord through the prophet, saying, Out of Egypt I called My Son” (Matthew 2:12-23). The Bible identifies Egypt as the refuge the Holy Family sought while fleeing Judea.

According to Coptic tradition, St. Mark is believed to have brought Christianity to Egypt around 50 CE. A small Christian community began to form in Alexandria during the late first century and expanded significantly by the end of the second century. Certain similarities in beliefs aided the acceptance of Christianity among Egyptians, including the dual nature of the Egyptian god Osiris as both human and divine, the resurrection of Osiris, and the divine triad consisting of Osiris, Isis, and Horus.

The ancient Egyptians, classical Greeks, and Romans primarily shaped the Coptic period in Egypt. This influence is evident in Coptic art, particularly in textiles that often feature ancient Egyptian symbols and motifs, such as the ankh, representing life. The ankh served as an alternative to the Christian cross; certain textiles display both symbols. Nevertheless, Coptic art predominantly reflects the more substantial impact of Greek and Roman traditions.

I’ve been unwell and facing difficulties lately (wearing out my apparatus and equipment in old age!), so I haven’t been able to post regularly. However, now that my illness is in a stillstand modus, I’m giving it a try!

Here, I present Marie Grillot‘s captivating account of the Christian Copts’ arrival in Egypt, their artistry, and their harmonious, peaceful way of life.

The Christian Necropolis of Bagawat

via égyptophile

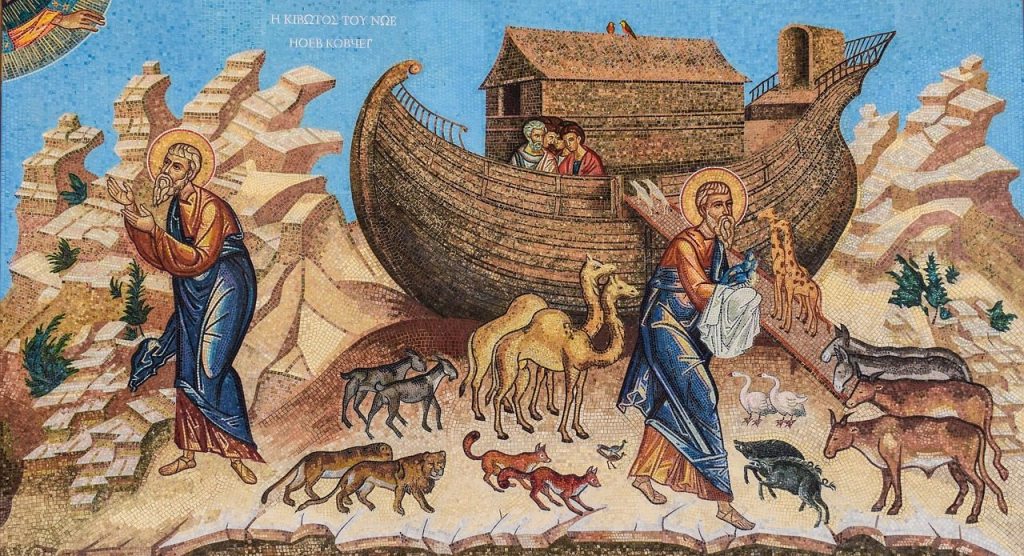

“The central image shows the patriarch and his family in the ark. Two doves overlap between the praying Mary and the ship.

The alliance with Noah finds its fulfilment with the Annunciation” – Christian necropolis of Bagawat – Kharga Oasis – 5th – 6th centuries.

A little over a kilometre northwest of the temple of Hibis, in the oasis of Kharga, stretches a ridge about twenty meters high on the edge of the desert. It is the remains of a site from the very beginning of Christianity in Egypt.

This is the Bagawat necropolis, which was active from the 2nd to the 7th century. It is so unique that it is sometimes referred to as Coptic, Roman, Byzantine, or even Greco-Coptic or Romano-Byzantine.

The middle of the first century of our era witnessed the arrival of Christianity, which caused proselytism to spread along the Nile… The edicts of Theodosius I, promulgated in 380 and then 391, led to the banning of pagan rites and the official closure of temples. The Copts, the first Christians in Egypt, affirmed their new faith and beliefs, engendering a new iconography and architecture… From its beginnings, Coptic art would draw inspiration from different cultures: Roman, Byzantine, Greek, and even Pharaonic.

During its 500 years of “activity,” in addition to digging hundreds of scattered pit tombs, the necropolis will see the construction of 263 chapels, examples of proto-Coptic art, surrounding a church built around the 4th century. As in Roman and Byzantine cemeteries, they are arranged along streets. Although they differ in size and specific details of their architectural structure, they restore an extremely harmonious overall unity.

“The funerary chapels are built of mud brick, in most cases originally covered with white plaster on the outside and inside. Externally, they present an architectural mixture of classical and ancient Egyptian motifs, often with a “cavetto” type cornice and classical forms of engaged columns with Corinthian capitals. They are generally square and covered with domes on pendentives or, less frequently, rectangular with barrel vaults. In a few cases, the remains of wooden roofs are visible. On each of the three walls of the Chapel, except the entrance wall, there is usually a niche, while a few chapels have a projecting apse at the eastern end. These apsidal ends are either circular or octagonal. Some of the larger buildings consist of a double Chapel of two square compartments, while a few have front courts surrounded by a wall of columns and engaged arches,” analyzes Albert M. Lythgoe in “The Oasis of Kharga”.

In “Enciclopedia dell’ Arte Antica” (1973), H. Torp describes “two basic types of construction. The first is very simple, with a square or rectangular plan and with a roof of wooden beams. The other type is square, covered with a dome. Of the first type, there are a little over a hundred tombs; of the second, a little less. The other mausoleums are variants or combinations of these two types, except for a limited number of circular or rectangular mausoleums with a barrel vault, as well as five large structures composed of several rooms, partially covered with vaults or a roof”.

The painters who worked in Bagawat were the vectors of diverse influences, which they combined, adapted and enriched, thus making this necropolis an exceptional place.

In “The Necropolis of el-Bagawat in Kharga Oasis”, A. Fakhry indicates that twenty-two of these chapels have “painted decorations, but only seven contain figurative art, the others showing only painted crosses or the like”.

Three chapels are particularly notable for their paintings.

The Chapel of Peace (No. 30) dates from the 5th and 6th centuries. For experts, its decoration is unique in early Christian art. The biblical themes, with characters (from the front!), are treated in shades of ochre, purple and red while respecting the perspectives the dome-shaped structure certainly made difficult to execute. This is a “unique register of sophisticated representations of biblical figures ‘labelled’ Greco-Coptic which includes allegorical images of peace, prayers and rigour alongside Daniel, Jacob, Noah, Mary, …”

The style and quality of the paintings “reflect a level of technical skill far superior to that of other surviving decorations from the necropolis. The artist who painted them appears to have had formal training” (Matthew Martin).

The Chapel of the Exodus (No. 80), whose centre of the dome is decorated with vine branches and filled with birds and naive trees, owes its name to its representations linked to the Hebrews’ departure from Egypt. It is declined in several scenes, such as Noah’s Ark, Daniel in the lion’s den, the three Jews in the furnace, the martyrdom of Isaiah, and episodes from the stories of Jonah and Job…

As for chapel no. 25, it offers magnificent white birds “standing on globes which support with their outstretched wings a solar disk covering the dome raised in the centre of the room.”

Thus, the domes and apses of the tombs and chapels contain “some masterpieces of Coptic painting, illustrating themes from the Old Testament and early Christianity, in a Hellenistic and Roman style. Wealthy Greeks certainly commissioned the paintings represented. Most of the frescoes are painted in red and purple tones, in a naive style but executed with great detail” (Hervé Beaumont, “The Necropolis of El-Bagawat” – Egypt: the guide to Egyptian civilizations, from the pharaohs to Islam).

Bagawat is an exceptional place, both architecturally and pictorially. It turns out to be, in a way, at the confluence of influences from the beginning of the Christian era…

It once again proves that religion is an immense source of inspiration for artists: to magnify their faith, they draw from the depths of themselves treasures of imagination and creativity to honour and glorify what is highest…

Sources:

Albert M. Lythgoe, The Oasis of Kharga, The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin, 1908-11-01 https://archive.org/details/jstor-3253214/page/n1/mode/2up W. Hauser, The Christian Necropolis in the Khargeh Oasis, BMMA 27, March 1932, The Metropolitan Museum of Art https://www.metmuseum.org/pubs/bulletins/1/pdf/3255361.pdf.bannered.pdf?fbclid=IwAR1p4UODOMBAj8dYj_p9nCPa2fj6m7fZrNc7OXTinm8mJES3Tjgtr5fPp7s H. Torp, el BAGAWAT, Enciclopedia dell’Arte Antica, 1973 http://www.treccani.it/enciclopedia/el-bagawat_%28Enciclopedia-dell%27-Arte-Antica%29/ Hervé Beaumont, The Necropolis of El-Bagawat, Egypt: the guide to Egyptian civilizations, the pharaohs to Islam, Gallimard, 2000 Matthew Martin, Observations on the Paintings of the Exodus Chapel, Bagawat Necropolis, Kharga Oasis, Egypt, Byzantine Narrative, Papers in Honour of Roger Scott, Australian Association for Byzantine Studies, Byzantina Australiensia 16, John Burke, Ursula Betka, Penelope Buckley, Kathleen Hay, Roger Scott & Andrew Stephenson, Melbourne, 2006 https://www.academia.edu/364953/Observations_on_the_Paintings_of_the_Exodus_Chapel_Bagawat_Necropolis_Kharga_Oasis_Egypt

You must be logged in to post a comment.