Erich von Däniken: The Ancient Astronaut Theorist

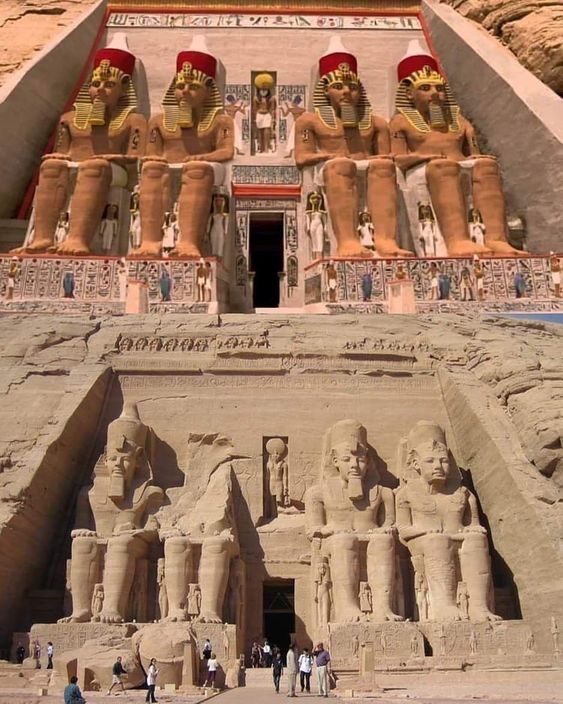

Erich von Däniken (born 14 April 1935 in Zofingen, Switzerland; died 10 January 2026) became one of the most controversial and successful writers of the 20th century. He gained worldwide recognition with his 1968 bestseller “Chariots of the Gods?”—a book that offered a radical reinterpretation of ancient history and archaeology. Däniken’s main thesis is that ancient extraterrestrial visitors contacted early civilisations, which explains structures such as the Egyptian pyramids, the Nazca Lines, and the Easter Island heads as either built using alien technology or as tributes to alien visitors. He proposes that gods described in religious texts are actually misinterpreted encounters with highly advanced extraterrestrials.

Von Däniken’s work has had a notable yet controversial impact. “Chariots of the Gods?” sold millions worldwide and sparked an entire genre of “ancient astronaut” literature and media. His ideas have captivated the public and influenced pop culture, from documentaries to science fiction. However, his theories are largely rejected by the scientific and archaeological communities. Critics point out that he often misuses archaeological data, ignores conventional explanations for ancient accomplishments, and underestimates the skills of ancient civilisations. Scholars argue that his theories rely on selective evidence, logical errors, and a basic misunderstanding of scholarly methods. Many also note that his ideas subtly undermine the achievements of ancient peoples, particularly non-European cultures.

Despite facing extensive academic criticism, von Däniken continues to be a cultural icon. His work raises lasting questions about our interpretation of history and highlights humanity’s fascination with extraterrestrial life. Whether regarded as a visionary challenging conventional views or accused of pseudoscience, Erich von Däniken has undeniably influenced popular culture and public discussions about ancient mysteries.

Al and I first encountered him, or rather his books, in the early seventies. In Iran, as I may have mentioned earlier, it is possible to find any book translated into Persian, even though the readership is limited; publishers endeavour to publish as many as they can.

We were genuinely intrigued and, as expected, valued his opinions on the space gods. Years later, in Bern, Switzerland, we met him in person at a three-day conference on Aliens, Abductions, and the eyewitnesses of those events. Interestingly, he was delighted to meet two brothers from Iran who spoke German, and they managed to recount their encounters with extraterrestrials.

In the spring of 2016, my lovely wife bought some surprise tickets for us to drive to Menden, a town not too far away, to meet the archaeologists and mythologists she knew I was connected with on Facebook and was fascinated by their work, like Robert Bauval, David Roll, Graham Hancock, Brien Foerster… and, of course, Erich von Däniken. There, I met him again, though alone because Al had already passed between the stars. I tried to introduce myself when I saw him, but astonishingly, he recognised me immediately and asked about Al, my brother! That was my last encounter with him, and I cherish having known him so well.

“Wherever the spirit would go, they would go, and the wheels would rise along with them, because the spirit of the living creatures was in the wheels. When the creatures moved, they also moved; when the creatures stood still, they also stood still; and when the creatures rose from the ground, the wheels rose along with them, because the spirit of the living creatures was in the wheels.” Ezekiel 1:20-21

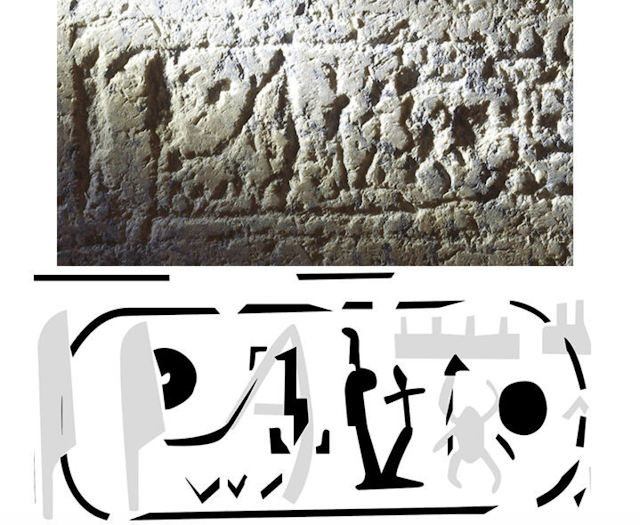

One of his most recognised theories relates to the prophet Ezekiel. Erich von Däniken’s Ezekiel theory is a well-known example of his “ancient astronaut” hypothesis. Von Däniken interpreted Ezekiel’s vision of the Merkabah, or wheeled chariot, as a spacecraft used by an advanced civilisation to travel through space and establish contact, rather than as a divine vision.

In the Book of Ezekiel, the prophet describes seeing a wheeled chariot descending from the sky. Von Däniken noted that the original Hebrew text does not mention God; the term was added later. Ezekiel’s account of the landing of the wheeled chariot closely resembles a spacecraft, with the windstorm, lightning flashes, and bright lights reminiscent of a spaceship arriving.

Ezekiel describes a scene, ‘a wheel within a wheel’, with fiery lights and movement, depicting something coming from the north as a large cloud with “flashing lightning and brilliant light around it.’ The prophet also describes four “living creatures” with wings and complex faces, which are often interpreted as alien pilots or robotic beings accompanying the craft.

For von Däniken, Ezekiel’s biblical account of God’s appearance on Mount Sinai was nothing more than a spaceship landing. This interpretation appeared in his 1968 bestseller Chariots of the Gods?, which sold over 70 million copies worldwide.

In the 1970s, von Däniken’s theory influenced NASA scientist Josef F. Blumrich, who initially regarded Ezekiel’s vision as a space shuttle. This inspired Blumrich to write a book that sought to challenge von Däniken’s ideas, thereby creating a conflict with his own thesis.

Erich von Däniken passed away at age 90 on 11 January 2026 in a hospital in central Switzerland. With his death, the world has lost an unconventional and courageous theorist of ancient human mysteries.

You must be logged in to post a comment.