Usermaatre Amenemope was an ancient Egyptian pharaoh of the 21st Dynasty who ruled between 1001 and 992 BC or 993 and 984 BC. His tomb is one of only two entirely intact royal burials known from ancient Egypt, the other being that of Psusennes I. “His Instruction” (That is about thirty chapters (more than ten commands!)) is a literary work from ancient Egypt, most likely composed during the Ramesside Period. It contains thirty chapters of advice for successful living, attributed to the scribe Amenemope, son of Kanakht, as a legacy for his son.

The pharaohs of Egypt were associated with Horus since the pharaoh was considered the earthly embodiment of the god. From around 3100 BCE, he was given a memorable royal “Horus name.” The falcon, representing divine kingship, symbolized the king as the earthly manifestation of Horus.

Here is the captivating story, by the brilliant Marie Grillot, of this incredible discovery.💖🙏

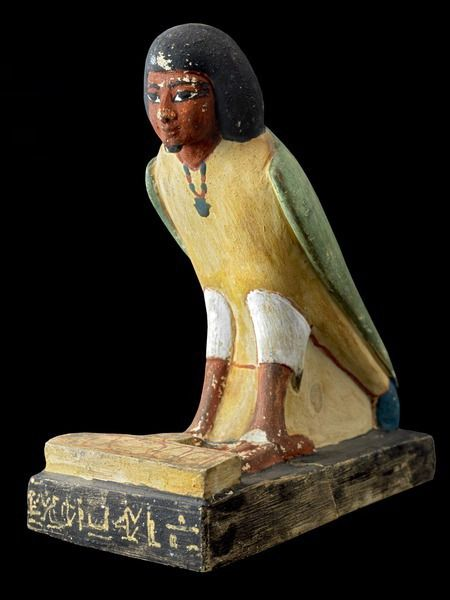

A falcon carrying Amenemopé’s cartridges in its talons

Via égyptophile

21st Dynasty – reign of Amenemopé (c. 1000 BC)

from Tanis, the tomb of Amenemopé – NRT III – discovered by Pierre Montet on April April 16

on display at the Egyptian Museum in Cairo – JE 86036 (museum photo)

In May 1929, the Egyptian government awarded Pierre Montet the concession for Tanis, now known as “Sân el-Hagar”, which lies in the “Tanitic branch” of the Nile Delta, over 100 km northeast of Cairo.

In 1722, Père Sicard identified this city as the ancient Tsa’ani” (“Tso’an” in Hebrew, “Tjaani” for the Copts, Greekized as “Djanet”). The scholars of the Commission d’Egypte partially excavated it, first by Jean-Jacques Rifaud (on behalf of consul Drovetti) and then by Auguste Mariette.

Its ruins, covering more than 400 hectares, witness its “activity” from the Old Kingdom to Roman times. However, the rulers of Dynasties XXI to XXIII marked its golden age by choosing it as their religious and funerary capital. By mirror effect, it became the “Thebes of the North”…

Pierre Montet’s team, summarily installed on this isolated and desolate site, worked with patience and perseverance for around ten years before the time came for the “rewards”. It was inaugurated in March 1939 with the discovery of the tomb of Chechonq II… From then on, the necropolis would yield many other treasures…

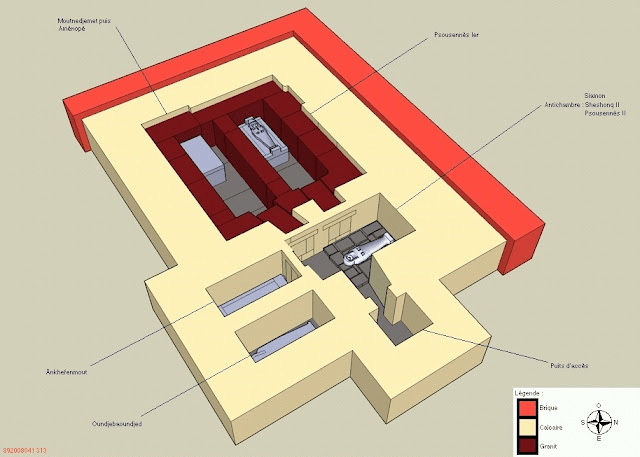

then their son Amenemopé, another son of king Ânkhefenmout, the king’s chief general Oudjebaoundjed,

and in the antechamber, the sarcophagus of Sheshonq II – Royal Necropolis of Tanis

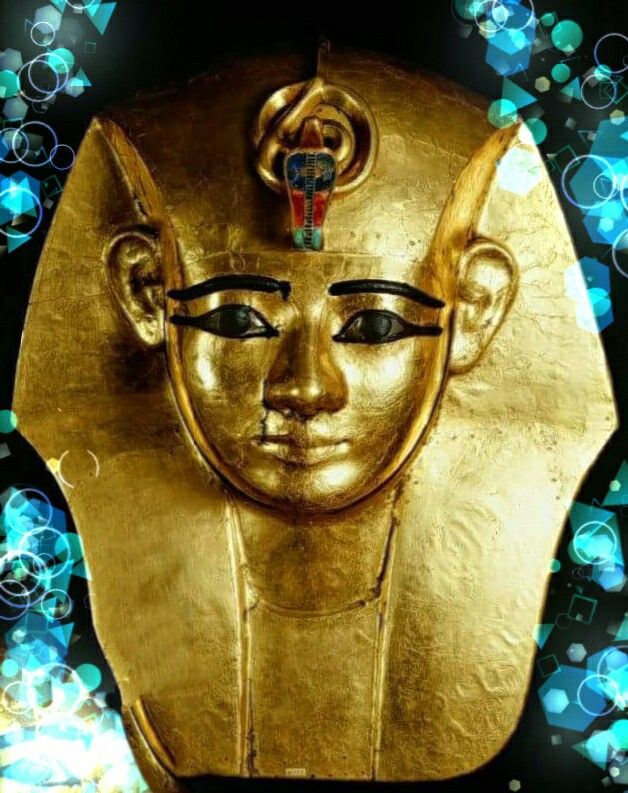

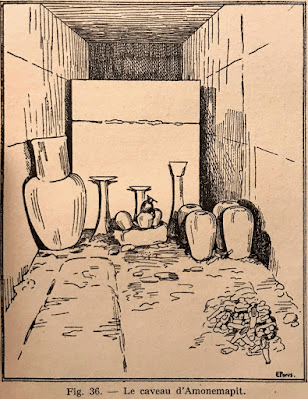

Thus, in “Tanis – Twelve years of excavations in a forgotten capital of the Egyptian Delta”, the Egyptologist Pierre Montet recounts the extraordinary day of the discovery of the tomb of Pharaoh Amenemopé: “The entrance was opened on April April 16). His Majesty King Farouk, who had arrived the day before in Saan, where he had erected a city of tents, was present, as was Canon Drioton, Director of the Egyptian Antiquities Service, and a young Egyptian Egyptologist, Professor Abou Bekr. The vault was furnished in much the same way as that of Psousennès: a granite sarcophagus at the bottom, canopic vases, metal vases, a large sealed jar, funerary statuettes and a vast gilded wooden chest that had collapsed due to the effects of time and humidity in the front half. Once these objects had been safely removed, the sarcophagus lid was placed in their place. Much less opulent than Psousannes, the new ruler had made do with a single stone sarcophagus and a wooden anthropoid coffin lined with gold. Wood was reduced to almost nothing. The gold plates were removed. Needless to say, the mummy had suffered enormously. His ornaments, less numerous than those of Psousennès, nevertheless constitute a wonderful collection: a gold mask, two necklaces, two pectorals, two scarabs, lapis and chalcedony hearts, bracelets and rings, a large cloisonné gold falcon with outstretched wings…”.

21st Dynasty – reign of Amenemopé (c. 1000 BC)

from Tanis, the tomb of Amenemopé – NRT III – discovered by Pierre Montet on April April 16

on display at the Egyptian Museum in Cairo – JE 86036 (museum photo)

The hawk, which seems to soar powerfully into the sky, is 10.5 cm high and 37.5 cm wide. The head and legs are in gold, while the rest of the body is in gold cloisonné with pâte de verre in shades of green, perfectly simulating the shimmer of the feathers.

In “Les trésors du musée égyptien”(The Treasures of the Egyptian Museum), Silvia Einaudi describes it as follows: “The falcon is depicted in flight with its wings spread. The head, turned to the left, is made of solid gold. The beak, eye, neck and decorative motif on the cheek are in dark pâte de verre. The raptor’s wings, body and tail are executed using the cloisonné technique: glass paste in delicate shades of pink and green is inlaid with gold, giving life to a simple polychromy. The wing feathers radiate outwards, forming two rows.

On the other hand, the body is decorated with a teardrop motif that continues right down to the tail. The legs, also in solid gold, hold the ‘shen’ signs, a symbol of eternity, to which two gold plates bearing the sovereign’s name are attached. The hieroglyphs inside the cartouches are executed in coloured glass paste inlaid with gold. The plate on the right bears the pharaoh’s coronation name: ‘Usermaatra Setepenamon, beloved of Osiris and Ro-Setau (Memphis necropolis)’; on the left, his birth name: ‘Ménémopé Meramon, beloved of Osiris, lord of Abydos'”.

Amenemopé, pharaoh of the 21st Dynasty, reigned from Tanis around 1001-992 BC. The successor of Psusennes I, he was, as the book mentioned above states: “buried in the latter’s tomb, in a granite-covered room originally created to house the remains of Moutnedjemet, wife and sister of Psusennes I”. We can only wonder why this small vault was chosen as his burial place when he “had” his own tomb referenced NRT IV (NRT = Nécropole Royale de Tanis).

21st Dynasty – reign of Amenemopé (c. 1000 BC)

from Tanis, the tomb of Amenemopé – NRT III – discovered by Pierre Montet on April April 16

on display at the Egyptian Museum in Cairo – JE 86059

On May 3, May 3, in a truck protected by the army, Amenemopé’s treasure made its way to the Egyptian Museum in Tahrir Square. The falcon-shaped pendant was registered in the Journal des Entrées under reference: JE 86036.

As for Pierre Montet’s team, the dramatic events of the Second World War forced them to end their quest for the past of Tanis and turn their attention to the tragic present. Excavations will not resume until the end of the conflict…

Sources :

The Hawk of King Amenemope http://www.globalegyptianmuseum.org/record.aspx?id=15530 Pierre Montet, Tanis – Twelve years of excavations in a forgotten capital of the Egyptian Delta, Payot, Historical Library, 1942

Pierre Montet, The royal necropolis of Tanis according to recent discoveries, Reports of the Academy of Inscriptions and Belles-Lettres sessions, 89th year, N. 4, 1945. pp. 504-517, Perseus https://www.persee.fr/doc/crai_0065-0536_1945_num_89_4_77901 Georges Goyon, The discovery of the treasures of Tanis, Pygmalion, 1987

Jean Yoyotte, Tanis l’or des pharaons, exhibition catalog Paris, National Galleries of the Grand Palais, March 26 – July 20, 1987, Association Française d’Action Artistique, 1987

Henri Stierlin, Christiane Ziegler, Tanis Trésors des pharaons, Seuil, 1987

Francesco Tiradritti, Treasures of Egypt – The wonders of the Egyptian Museum in Cairo, Gründ, 1999

Pharaons – Catalog of the exhibition presented at the Institute of the Arab World in Paris, from OctobeOctober 15 to April April 10, IMA, Flammarion, 2005

Posted 5th MaMarch 5by Marie Grillot

You must be logged in to post a comment.