It has been a while since I last published a post about Egypt, and now, perhaps in the spirit of the Egyptian sense of rebirth, I have decided to give it a try.

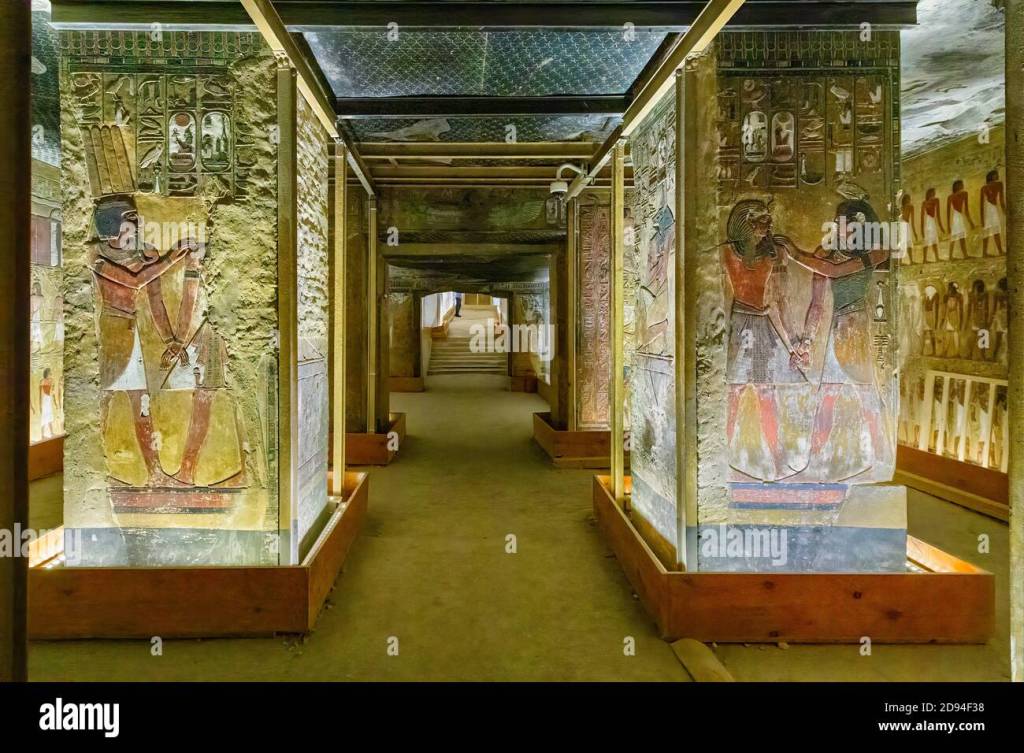

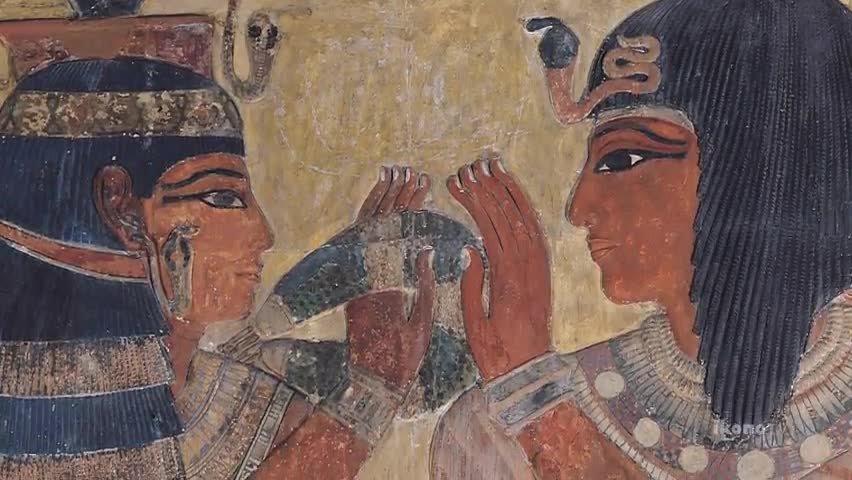

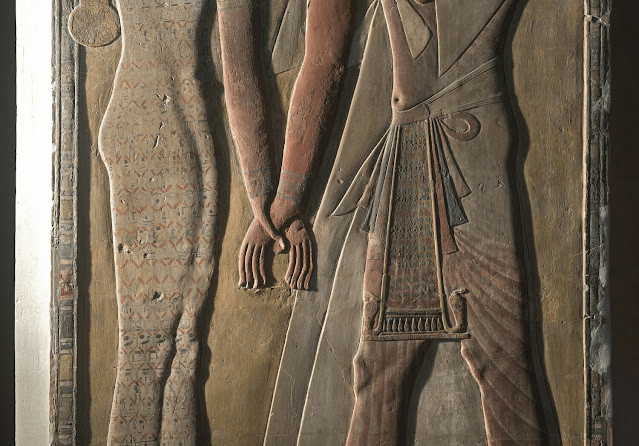

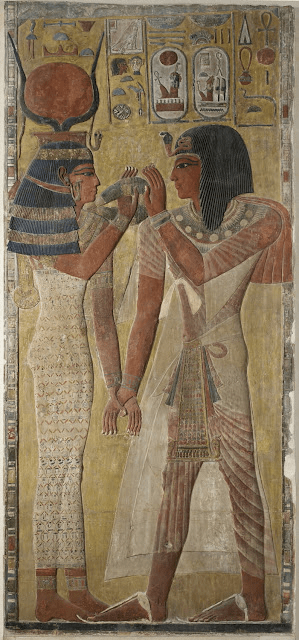

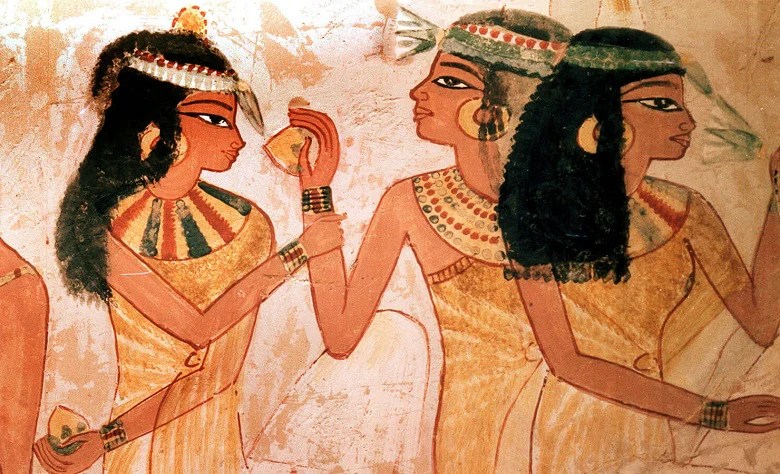

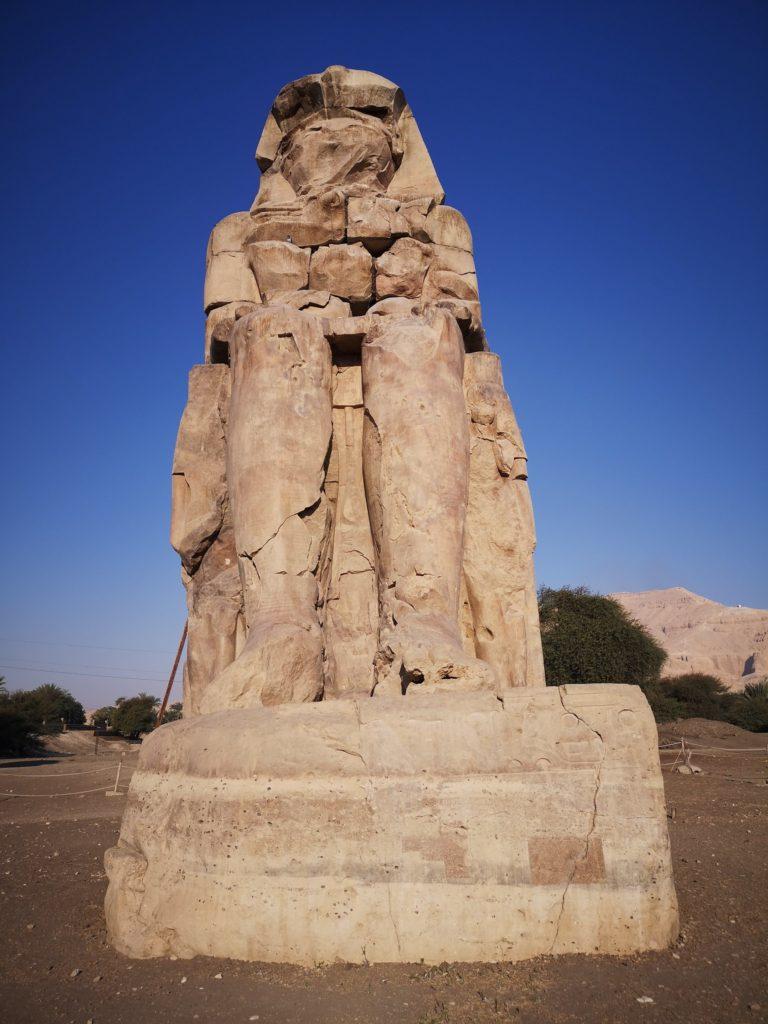

Tomb KV17 in Egypt’s Valley of the Kings is the resting place of Pharaoh Seti I from the 19th Dynasty. It is also known as “Belzoni’s tomb,” “the Tomb of Apis,” and “the Tomb of Psammis, son of Necho.” As one of the most elaborately decorated tombs in the valley, it is now almost always closed to the public due to damage. The longest tomb in the valley, measuring 137.19 metres (450.10 feet), features well-preserved reliefs in all but two of its eleven chambers and side rooms.

Here is an excellent recount of this discovery by the esteemed Marie Grillot. I believe you will find it quite engaging.

Sources: Madain Project & Ancient Egypt Magazine

The Discovery of Seti I’s Alabaster Sarcophagus by Belzoni

via égyptophile

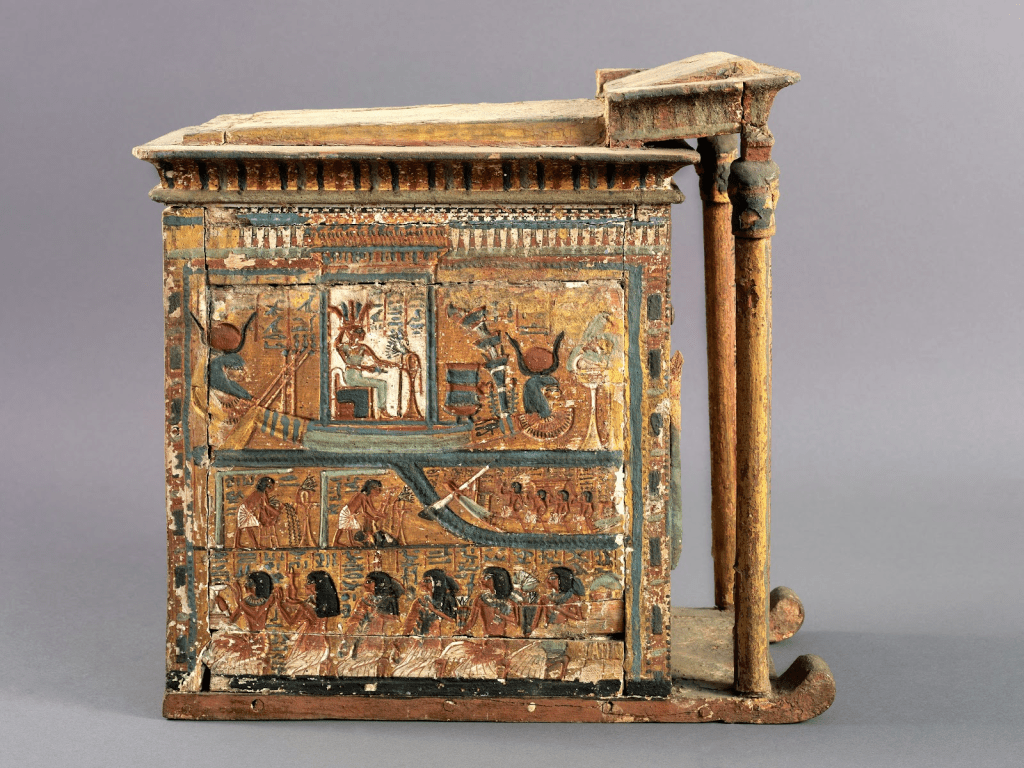

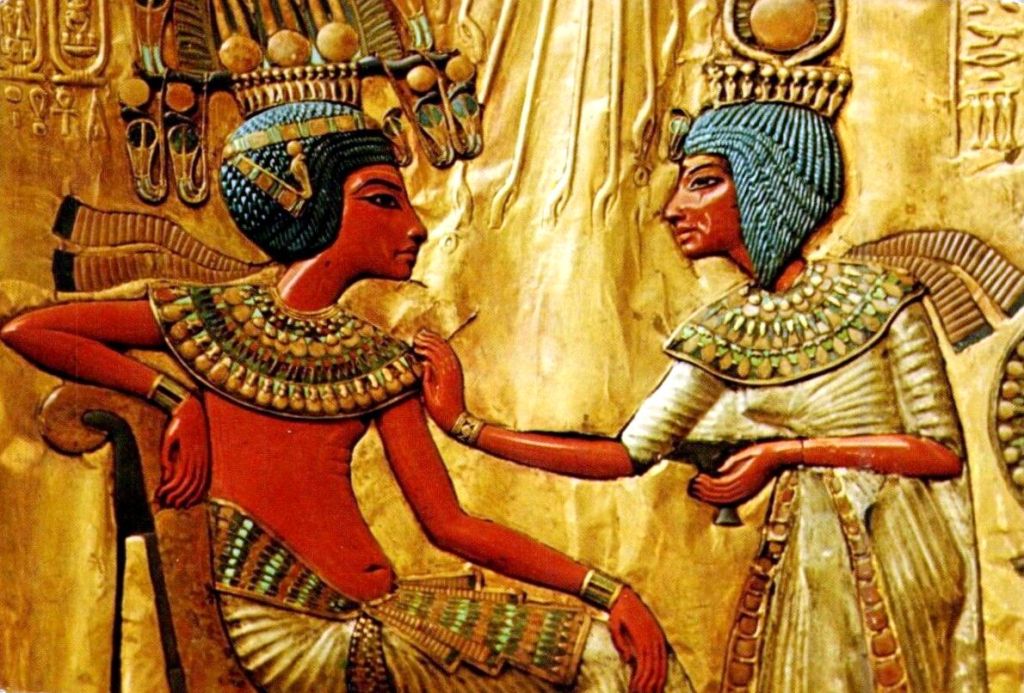

carved and incised calcite (Egyptian alabaster), with traces of ‘Egyptian blue’ filling – New Kingdom – 19th Dynasty – circa 1279 BC

discovered in October 1817 in the tomb of Seti I (KV 17) by Giovanni Battista Belzoni on behalf of Consul Henry Salt

Sir John Soane’s Museum, London – inventory no.: M470 (acquired in May 1824)

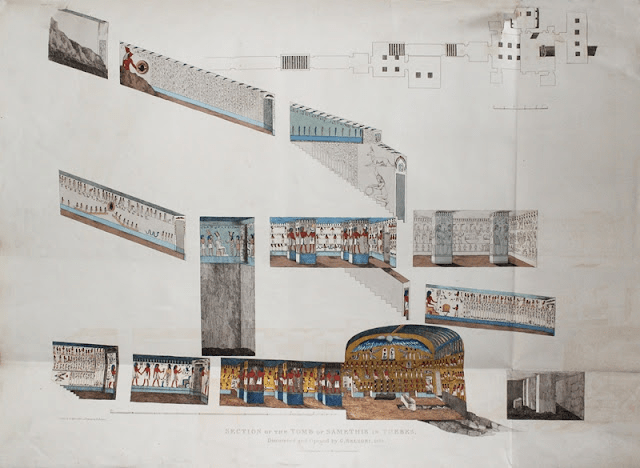

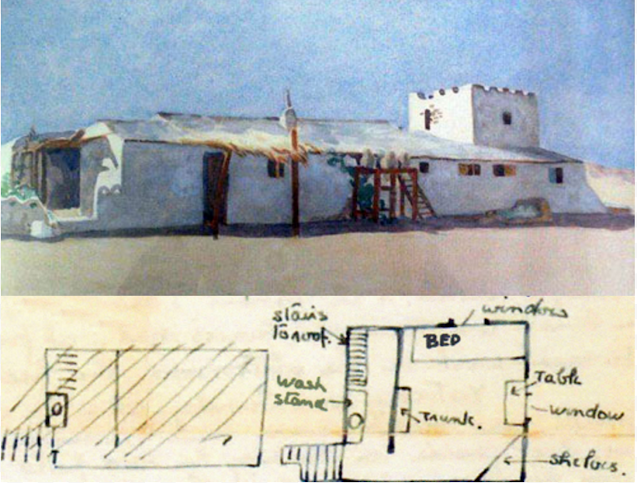

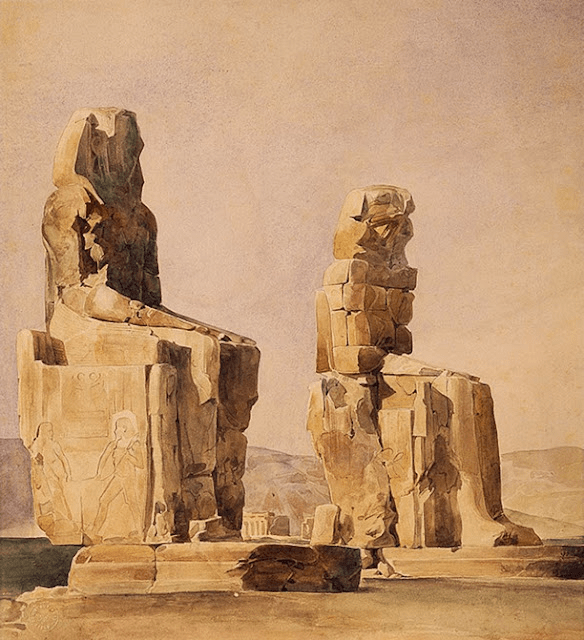

watercolour by Joseph Michael Gandy, dated September 9, 1825

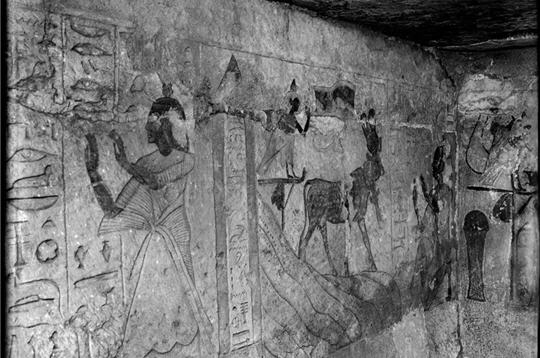

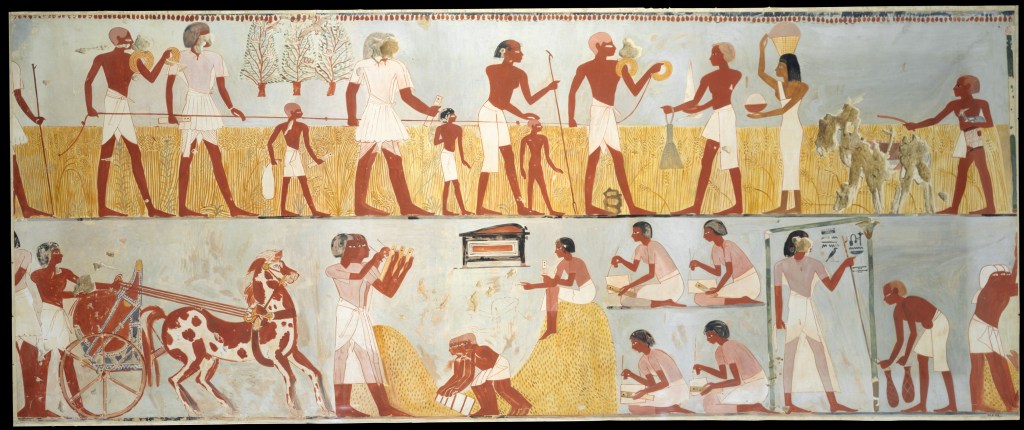

On October 18, 1817, Giovanni Battista Belzoni discovered, in the Valley of the Kings, an immense tomb with walls covered in magnificent scenes. He was captivated by what lay before him… “I can call the day of this discovery one of the most fortunate of my life,” he recalled in “Travels in Egypt and Nubia.” “I judged, by the paintings on the ceiling and by the hieroglyphs in bas-relief that could be distinguished through the rubble, that we had gained access to a magnificent tomb.”

He could not have known then that this was the “first tomb to be decorated with a complete program of religious texts” (“Theban Mapping Project”), nor could he have presumed to whom it belonged…

© The Trustees of Sir John Soane’s Museum

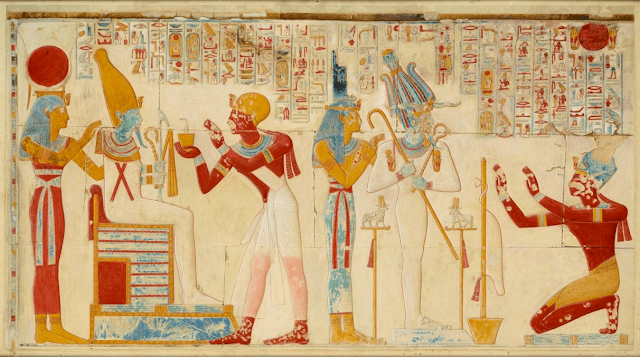

In reference to the “carcass of a bull embalmed with asphalt” found there, it was called the “Tomb of the Apis” or, at times, the “Belzoni Tomb.” Then, due to a misinterpretation by Thomas Young, it was attributed to “Nichao and his son Psammis”; for Joseph Bonomi, it was the “Tomb of Oimeneptah I.” It was thanks to the deciphering of the hieroglyphs by Jean-François Champollion in 1822 that it could finally be identified as the tomb of Seti I. Originally from the Delta, the true founder of the 19th Dynasty, this military man, astute politician, and great builder reigned over the Two Lands for eleven years (1294 to 1279 BC). Very early on, he associated his son with the throne, who succeeded him as Ramses II.

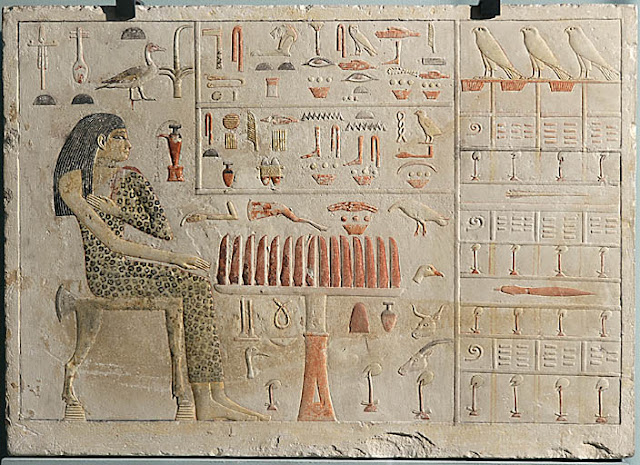

Discovered in March 1904 in the Karnak Cachette by Georges Legrain for the Antiquities Service directed by Gaston Maspero

Previously in the Cairo Museum – JE 36692 – CG 42139 – On display since 2007 at the Luxor Museum (Gallery J)

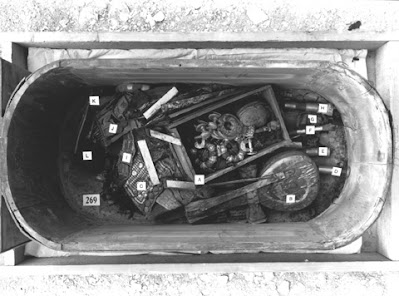

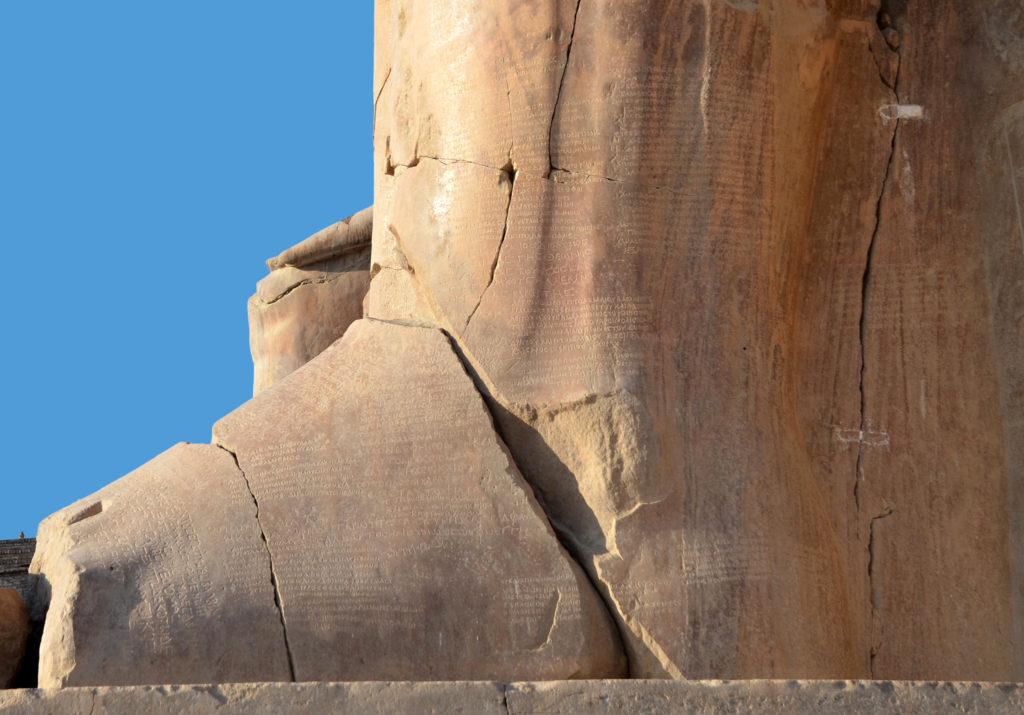

The hypogeum (which much later would be referenced as KV 17) descends 137 m into the Theban mountain through 7 corridors and has 10 rooms! Belzoni goes from wonder to wonder, and his admiration reaches its peak when he arrives in the sarcophagus room. “The paintings were all executed with such perfection that I felt compelled to call this room the Hall of Beauties… But what this room offered, to our eyes, was most important: a sarcophagus placed in the centre, which has no equal in the world. This magnificent tomb, measuring nine feet five inches long by three feet seven inches wide, is made of the finest oriental alabaster: being only two inches thick, it becomes transparent when a light is placed behind one of the walls; inside and out, it is covered with sculptures: these are hundreds of small figures, no more than two inches high, which represent—it seemed to me—the entire funeral procession of the deceased placed in the sarcophagus, as well as emblems, etc. Unfortunately, the lid was missing: it had been removed and broken, and we found some fragments of it during the excavations in front of the first entrance.”

illustration by Joseph Michael Gandy dated 18 November 1825 – © The Trustees of Sir John Soane’s Museum

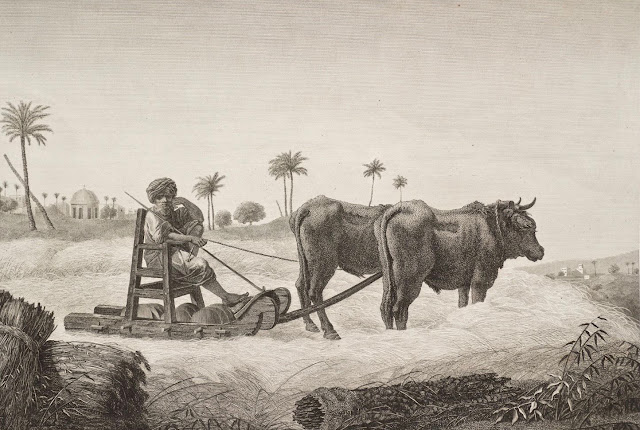

Belzoni was accustomed to perilous “manoeuvres”: it is worth recalling that, two years earlier, he had orchestrated the removal of the “Young Memnon,” which was taken from the Ramesseum and sent to the British Museum… But extricating the fragile sarcophagus from the tomb seemed an even more difficult task. He undertook it—after carefully assessing the risks—and apparently without neglecting to have his name engraved on the rim of the fragile coffin beforehand. “It was a very delicate operation because the walls of this tomb (sic) were so thin that the slightest shock could break them. However, it was removed from the underground chamber without incident and, as soon as it was outside, placed in a strong crate. The valley through which it had to be transported to reach the Nile offered more than two miles of uneven terrain, and one mile of flat ground, covered with sand and pebbles. We transported it by means of rollers, and we fortunately managed to load it,” recounts Jean-Jacques Fiechter in “The Harvest of the Gods” (quoting “epistolario”, letter no. 122).

New Kingdom – 19th Dynasty – circa 1279 BC – discovered in October 1817 in the tomb of Seti I (KV 17)

by Giovanni Battista Belzoni on behalf of Consul Henry Salt

Sir John Soane’s Museum, London – inventory number: M470 (acquired in May 1824) © The Trustees of Sir John Soane’s Museum

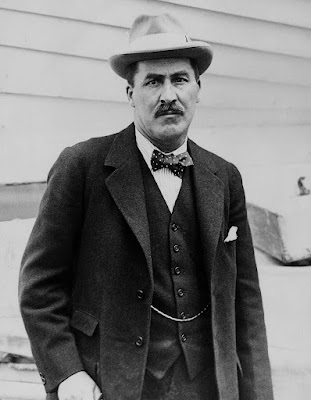

Upon his arrival in Egypt in June 1815, Belzoni, the “Titan of Padua,” had cultivated a close relationship with the French consul, Bernardino Drovetti, but ultimately entered the service of the British consul, Henry Salt, the following summer. In their quest for antiquities—the firmans they possessed granting them complete freedom in their excavations—the two “consul-collectors” were fierce rivals, and the term “War of the Consuls” is sometimes used. Henry Salt benefited from a substantial inheritance left to him by his father. This financial security allowed him to indulge his passion for ancient Egypt by building his own collection. Furthermore, he had an “official mission” to enrich the Egyptian department of the British Museum. Belzoni would become one of his most effective agents, not only in the field but also when it came to negotiating the sale of artefacts, even as far as London!

Diplomat, British Consul in Egypt from 1816 to 1835, collector of antiquities

In 1821, after travelling down the Nile and reaching Alexandria, the alabaster sarcophagus was loaded onto the frigate HMS Diana, which sailed for Great Britain. Stored at the British Museum, it was offered to them along with the “first Salt collection.” Negotiations with the London museum, which had just acquired Lord Elgin’s Parthenon Marbles for £35,000, proved difficult. While Salt had hoped to get £8,000 from his collection, after lengthy and bitter discussions, he had to sell it to them for… £2,000! As for the sarcophagus, which he offered them for 2,000 pounds, Brian M. Fagan recalls in “The Rape of the Nile: Tomb Robbers, Tourists, and Archaeologists in Egypt”: “The administrators categorically rejected the offer of the sarcophagus, due to both legal difficulties and the excessively high price, despite protests from Salt and Belzoni that they had received higher offers from Drovetti and other buyers. Ultimately, the sarcophagus was sold for 2,000 pounds to John Soane, a wealthy London architect and art collector.”

This “eclectic” collector had been completely fascinated by Belzoni’s adventures, as well as by the exhibition “The Egyptian Tomb” (on the tomb of Seti I) that the latter organised, with his wife Sarah, at the Egyptian Hall in Piccadilly, London, and which he had visited on June 8, 1821… He would have to wait until May 12, 1824, to be able to acquire the sarcophagus, the purchase of which had been stubbornly refused by the British Museum…

In “Sir John Soane’s Greatest Treasure, The Sarcophagus of Seti I”, John H. Taylor recounts the installation of the sarcophagus in Soane’s house at Lincoln’s Inn Field on May 12, 1824: “The door being too narrow to allow it to pass through, a wide opening had to be made at the rear of the house, and ropes were used to lower it to the basement, beneath the Soane Dome, into a space named ‘the sepulchral chamber’ in his honor. It made a perfect centrepiece for the ‘crypt’ of Soane’s museum, perfectly reflecting his self-proclaimed ‘melancholy and sullen’ personality.”

New Kingdom – 19th Dynasty – circa 1279 BC – discovered in October 1817 in the tomb of Seti I (KV 17)

by Giovanni Battista Belzoni on behalf of Consul Henry Salt

Sir John Soane’s Museum, London – inventory number: M470 (acquired in May 1824) – internet photo

A curatorial note from the Sir John Soane Museum, where it is displayed under inventory number M470, states: “This sarcophagus was acquired with, according to early records, 18 pieces of the lid (see X58 and X73; one of the pieces is actually part of a canopic jar and is now catalogued as museum number X74). The museum also has a cast of another piece of the lid displayed in 1961 (X164)… The sarcophagus consists of two monolithic alabaster blocks. It is inscribed over its entire surface with religious scenes and figures, which were then filled with a substance called ‘Egyptian blue’.” Although most of the blue filling has disappeared, traces remain here and there. The effect, when complete, must have been stunning… The Museum further explains that: “The Victorian display case that now protects the sarcophagus was installed in 1866. Previously, the coffin was displayed without a case, as Soane wished, simply mounted on four fluted columns. The display case, fitted with casters, can be disassembled into two parts. It was refurbished in 2007, and the thick Victorian glass, with its strong greenish tint, was removed for safety reasons and replaced with clear safety glass. This improved the sarcophagus’s visibility. The display case is now a museum piece in its own right. It has brilliantly protected this delicate sarcophagus—whose stone scratches easily and which could also be stained by water if the skylight above leaked—for over 150 years.” A brass frame now protects it…

New Kingdom – 19th Dynasty – circa 1279 BC – discovered in October 1817 in the tomb of Seti I (KV 17)

by Giovanni Battista Belzoni on behalf of Consul Henry Salt

Sir John Soane’s Museum, London – inventory number: M470 (acquired in May 1824) – internet photo

This magnificent and imposing mummy-like coffin, whose lid, broken in antiquity, must have borne the image of the pharaoh, is 284.5 cm long, 111.8 cm wide at the shoulders, 68.6 cm high, and its thickness varies from 2.5 to 10.2 cm. It is illustrated with funerary texts and vignettes taken from the “Book of Gates,” which is divided into twelve sections, corresponding to the twelve hours of the night…

To understand the admiration aroused by such an artifact, John H. Taylor quotes an excerpt from a newspaper article in the “Morning Post” of April 22, 1824: “We believe that there is no country in Europe which would not be proud to possess such a rarity and that the Emperor of Russia, in particular, would rejoice to obtain it, if it were possible to buy it from the liberal and patriotic individual who is its present owner”…

portrait published by his wife, Sarah, in 1824

As for Belzoni, who expressed his feelings about this exceptional piece thus: “Europe has never received from Egypt an ancient artefact of such magnificence,” he would be the big financial loser in the transactions… Indeed, as Brian M. Fagan reminds us, Henry Salt had promised him “half the price the sarcophagus would fetch above the paltry sum of two thousand pounds”… Not a single pound was ever paid to him…

Sources:

Sir John Soane’s Museum, London, Sarcophagus of Pharaoh Seti (or Sety) I, resting on four fluted stone columns – c.1279 BC – XIXth Dynasty – Museum number: M470

http://collections.soane.org/object-m470

Sir John Soane’s Museum, London, Case covering the sarcophagus of Seti I – 1866 – Museum number: M470.A

https://collections.soane.org/object-m470-a

Sir John Soane’s Museum, London, Cast of a fragment of the lid of the sarcophagus of Seti I – Museum number: X164

https://collections.soane.org/object-x164

Sir John Soane’s Museum London, Fragment of the lid of the sarcophagus of Seti I – Museum number: X73.A.i (et suivants…)

https://collections.soane.org/object-x73-a-i

Brian M. Fagan, The Rape of the Nile: Tomb Robbers, Tourists, and Archaeologists in Egypt, Book Club Associates, 1975

https://books.google.fr/books?id=CI84DgAAQBAJ&pg=PT113&lpg=PT113&dq=exhibition%20Belzoni%20Seti%20Saint%20Petersburg&source=bl&ots=cpZJr4hXvf&sig=COEiL_SQlWBptDjwcsh4Hy9VOAc&hl=fr&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwiBuPvggZfZAhWFzaQKHdkuDgEQ6AEIUzAH#v=onepage&q=exhibition%20Belzoni%20Seti%20Saint%20Petersburg&f=false

Giovanni Battista Belzoni, Voyage en Égypte et en Nubie, Pygmalion, 1979

Jean-Jacques Fiechter, La moisson des Dieux, Julliard, 1994

Brian M. Fagan, L’aventure archéologique en Égypte : Grandes découvertes, pionniers célèbres, chasseurs de trésors et premiers voyageurs, Pygmalion, 1997

Nicholas Reeves, Les grandes découvertes de l’Égypte ancienne, Éditions du Rocher, 2001

Nicholas Reeves, Richard H. Wilkinson, The Complete Valley of the Kings, American University in Cairo Press, 2002

Jean Vercoutter, À la recherche de l’Égypte oubliée, Découvertes Gallimard, 2007

https://books.google.fr/books?id=2IJnkBDoBBwC&pg=PA80&lpg=PA80&dq=exposition+egypte+boulevard+des+italiens+1822+paris&source=bl&ots=Sv3a4SiBkH&sig=kSl3FSh1RFMI2DB2URr9y9raz1Y&hl=fr&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwj9juyw15TZAhULL8AKHVFcC7wQ6AEIaTAD#v=onepage&q=exposition%20egypte%20boulevard%20des%20italiens%201822%20paris&f=false

John H. Taylor, Sir John Soane’s Greatest Treasure, The Sarcophagus of Seti I, Pimpernel Press Ltd, 2017

Pierre Tallet, Frédéric Payraudeau, Chloé Ragazzolli, Claire Somaglino, L’Égypte pharaonique, histoire, société, culture, Armand Colin, 2019

Theban Mapping Project, KV 17, Sety I

https://thebanmappingproject.com/tombs/kv-17-sety-i

You must be logged in to post a comment.