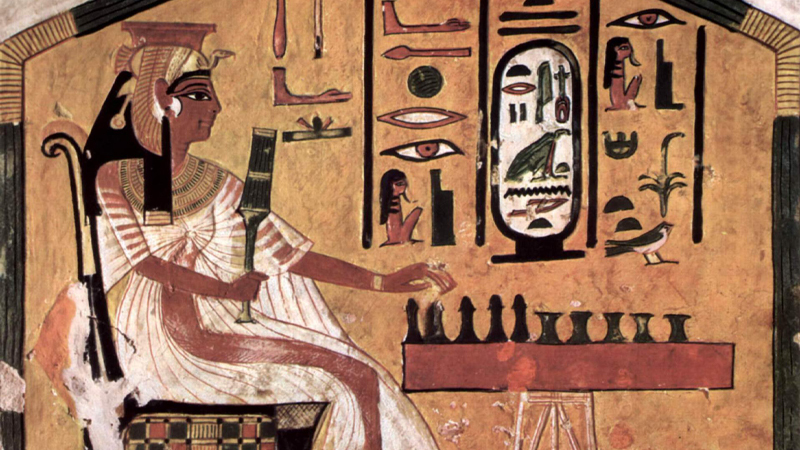

The ancient Egyptians had many beautiful women, including Queen Nefertari. She was known as “the most beautiful of them all” and was one of the most beloved queens of ancient Egypt, reigning during the 19th Dynasty. At the heart of the exhibition is Queen Nefertari, who was renowned for her beauty and prominence. She was called “the one for whom the sun shines” and was the favourite wife of Pharaoh Ramesses II.

One of the most famous figures from ancient Egypt is Queen Nefertiti. Her name, “the beautiful one has come,” has solidified her status as an iconic figure from the 14th century BC. She lived alongside her husband, Pharaoh Akhenaten, during the New Kingdom. Nefertiti’s legacy is steeped in mystery and fascination, as her renowned beauty and significant cultural impact have left a lasting impression.

Likewise: Queen Cleopatra, Queen Hatshepsut, Queen Neithhotep, Queen Tiye, Queen Twosret, Queen Nitocris… and Queen Ankhesenamun. Source: Jakada

But here, we have another one of beauty who remains unknown. Let’s read the story of its discovery by the privileged Marie Grillot.💖🙏

The Fair Lady of Lisht

via égyptophile

discovered in 1907 during excavations in the area of the pyramid of Amenemhat I in Lisht

by the Metropolitan Museum of Art Expedition, New York – Egyptian Museum, Cairo – JE 39390

The face is noble and perfectly symmetrical. The veins of the light wood give it a feeling of life. The general expression is gentle, calm, and peaceful.

The large almond-shaped eyes, of which only the orbits remain, are absent… and, despite this, they seem to question us… What presence did they give to the face? What did they reveal? Did the glass paste and rock crystal subtly and luminously animate their pupils? These questions remain forever unanswered.

The eyebrows are treated in relief, while the shadow line is treated in hollow. The nose is well-proportioned, and the lips are thin. The slight injury they suffered reminds us of the ravages of time.

discovered in 1907 during excavations in the area of the pyramid of Amenemhat I in Lisht

by the Metropolitan Museum of Art Expedition, New York – Egyptian Museum, Cairo – JE 39390

What, obviously, impresses in this head of barely more than 10 cm is the imposing wig that generously frames it and must have reached the level of the shoulders, which have now disappeared. “The enveloping mass of the added hair is worked in a darker wood and blackened with paint; it is fixed to the head in lighter wood, using tenons”, specify Mohamed Saleh and Hourig Sourouzian in their “Official Catalogue of Egyptian Museum in Cairo. The deep black of the wig is enhanced with small squares of gold leaf, which have so many luminous touches. On the other hand, Rosanna Pirelli analyzes in “The Wonders of the Egyptian Museum in Cairo”: “The fact that the wig is particularly fine at the top, compared to the width of the lateral parts, suggests the presence of a crown or a diadem.”

discovered in 1907 during excavations carried out in the area of the pyramid of Amenemhat in Lisht by the Expedition of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York – Egyptian Museum in Cairo – JE 39390

Who was this beautiful lady? A queen, a princess, a prominent person at the sovereign’s court? The work’s quality and the artist’s mastery, indeed, suggest that it may have come from the pharaoh’s workshops. Unfortunately, this face, which was that of a full-length statue, does not allow us to identify it.

This head—often used as a model to illustrate the beauty of ancient Egyptian women—was discovered in 1907 in Lower Egypt, precisely in Lisht, between Daschour and Meidoum.

discovered in 1907 during excavations in the area of the pyramid of Amenemhat I in Lisht

by the Expedition of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York – Egyptian Museum in Cairo – JE 39390 – illustrates numerous works

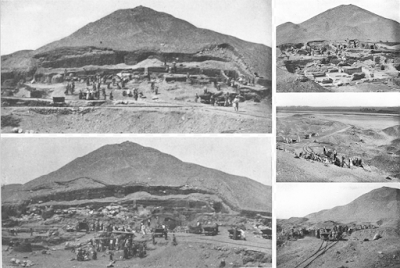

At the beginning of his reign, Amenemhat I “left Thebes to found a new city at the entrance to the Fayoum, named ‘Amenemhat-se-seizit-des-Deux-Terres’ not far from the current site of Lisht (“Pharaonic Egypt, history, society, culture”). In “L’Egypt Restorée”, Sydney Aufrere and Jean-Claude Golvin thus analyze the reasons which led to this “relocation”: “not only to break away from Thebes and the supporters of the last Montouhotep but also to keep an eye on the north and the Asian border, the city became the main royal residence during the 12th and 13th dynasties… They add, “Today we cannot give it any other reality and archaeological dimension than those which associate it with the two funerary monuments today reduced to two mounds: the pyramids of Amenemhat I and Sesostris I.”

during the discovery of the head of a female statue in painted wood with gilding (JE 39390) from the 12th dynasty

In 1882, Gaston Maspero, successor to Auguste Mariette at the head of the antiquities service, undertook excavations on the site, work that allowed the identification of the pyramids. For practical reasons (there was sometimes up to 11 m of water, he relates), however, he was unable to go as far as the burial chamber. The study of the site was then taken up in 1894-1895 by the French School of Cairo (which, in 1898, became the French Institute of Oriental Archeology).

Then, in 1906, when Gaston Maspero returned to the directorship of antiquities, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York requested the concession. He obtains it and then settles in for several seasons of excavation.

discovered in 1907 during excavations in the area of the pyramid of Amenemhat I in Lisht

by the Metropolitan Museum of Art Expedition, New York – Egyptian Museum, Cairo – JE 39390

Indeed, the Egyptian department of the MMA was created on October 15, 1906, and its administrators, as well as its brand new director, Albert Morton Lythgoe, saw the point of enriching their knowledge, experience, and collections.

Thus began their first campaign, financed by private funds, under the joint leadership of the director, Herbert Eustis Winlock (Harvard) and Arthur C. Mace (Oxford).

One hundred fifty workers were recruited: some, already ‘trained’ for excavations, came from Upper Egypt, others from neighbouring villages; their number will continue to increase over the years.

discovered in 1907 during excavations in the area of the Amenemhat pyramid in Lisht

by the Metropolitan Museum of Art Expedition, New York – Egyptian Museum, Cairo – JE 39390

reproduced for the first time in “The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin” n° 10 – Oct. 1907

Albert M. Lythgoe does not explain the exact circumstances of the head’s discovery. In the October 1907 bulletin of the MMA, although it appears in a photo with the caption “figure 2. Head of wooden statuette from Lisht, 12th dynasty”, no details are given on the place where it was found. The author relates that the excavations concerned two sectors: the cemetery located west of the pyramid of Amenemhat, which revealed tombs of important figures of the 12th dynasty, as well as a sector situated on a promontory. Over a hundred tombs have been unearthed for most of the 12th dynasty.

As the head is illustrated opposite this paragraph, we can think that its discovery is linked to these areas where dignitaries, relatives, and ruling family members had the honour of resting not far from the pharaoh.

It should be noted that her arms were found two years later, in Situ, by Herbert Eustis Winlock…

This head is displayed at the Egyptian Museum in Tahrir Square in Cairo under number JE 39380.

Sources:

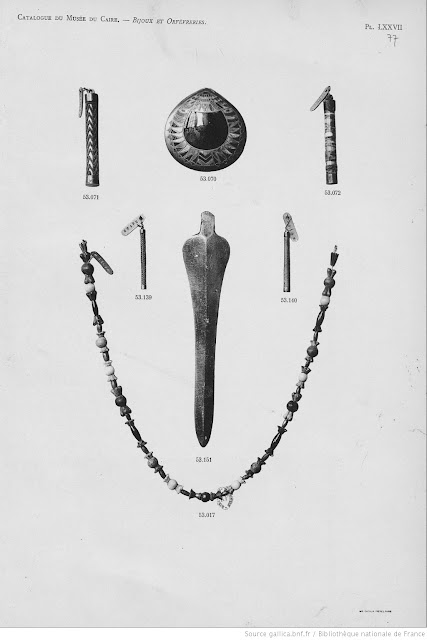

The head of a woman surrounded with a placed hairdressing consists of two pieces of blackened wood, inlaid with gold, Musée égyptien du Caire https://egyptianmuseumcairo.eg/artefacts/head-of-a-woman/ The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin, Vol. 1, No. 12, Nov. 1906 http://www.jstor.org/stable/i3634, http://www.jstor.org/stable/i363438 A. M. Lythgoe, The Egyptian Expedition, The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin, Vol. 2, No. 4, Apr. 1907 https://www.jstor.org/stable/i363442 The Egyptian Expedition, Albert M. Lythgoe, The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin, Vol. 2, No. 7, Jul. 1907, http://www.jstor.org/stable/3253292 The Egyptian Expedition, Albert M. Lythgoe, The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin, Vol. 2, No. 10, Oct.1907 https://www.jstor.org/stable/3253176?seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents Mohamed Saleh, Hourig Sourouzian, Catalogue officiel du Musée égyptien du Caire, Verlag Philipp von Zabern, 1987

Sydney Aufrère, Jean-Claude Golvin, L’Egypte restituée – Tome 3 – Sites, temples et pyramides de Moyenne et Basse Égypte, Editions Errance, 1997

Christiane Ziegler, L’Art égyptien au temps des pyramides, Réunion des Musées Nationaux, 1999

Francesco Tiradritti, Trésors d’Egypte – Les merveilles du musée égyptien du Caire, Gründ, 1999

Guide National Geographic, Les Trésors de l’Egypte ancienne au musée égyptien du Caire, 2004

Pierre Tallet, Frédéric Payraudeau, Chloé Ragazzolli, Claire Somaglino, L’Egypte pharaonique, histoire, société, culture, Armand Colin, 2019

Posted 29th October 2019 by Unknown

You must be logged in to post a comment.