Originally called Pa-ra-mes-su, Ramesses I, was of non-royal birth, born into a noble military family from the Nile Delta region, perhaps near the former Hyksos capital of Avaris. He was the son of a troop commander called Seti. His uncle Khaemwaset, an army officer, married Tamwadjesy, the matron of Tutankhamun’s Harem of Amun, a relative of Huy, the viceroy of Kush, a vital state post. This shows the high status of Ramesses’ family. Ramesses I found favour with Horemheb, the last pharaoh of the tumultuous Eighteenth Dynasty, who appointed the former as his vizier. Ramesses also served as the High Priest of Set – as such, he would have played an important role in restoring the old religion following the Amarna heresy of a generation earlier, under Akhenaten.

I once published an article about this amazing Pharaoh (Here), and now we are reading a supplement on this fascinating story.

Here, we will read Marie Grillot‘s excellent description of the mysteries surrounding the mummy of Pharaoh Ramses I.

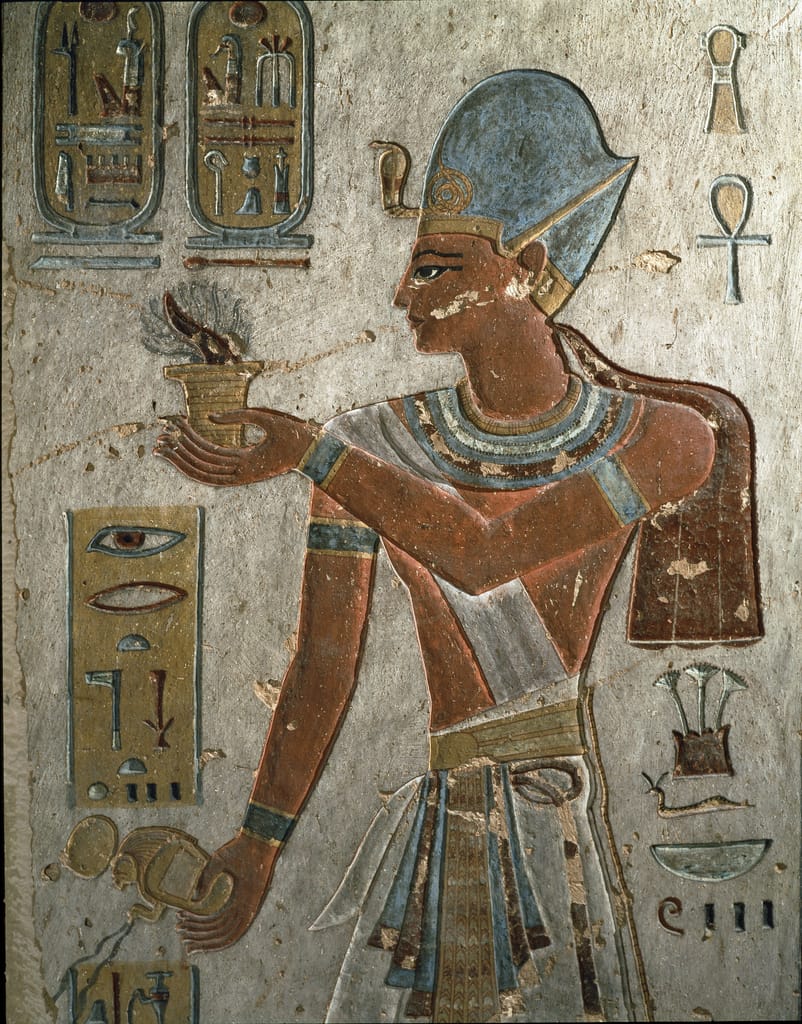

The image at the top, Egyptian Antiquities: Pharaoh Ramses I (1320-1310 BC), represents burning incense and pouring water at a ceremony. Volume of Ramses I, Valley of the Kings, Egypt (Meisterdrucke)

The tomb of Ramses I and the questions about his mummy…

via égyptophile

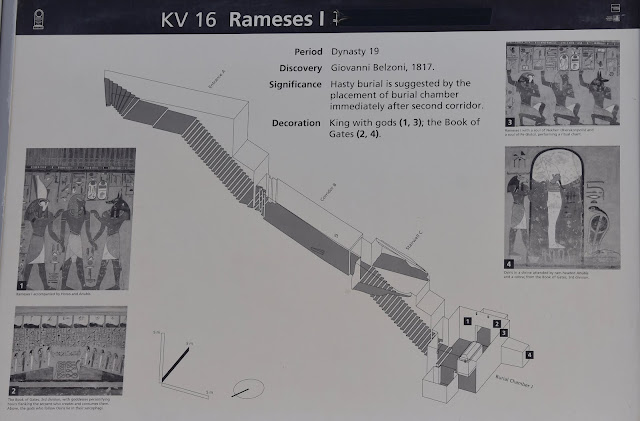

Tomb of Ramesses I – Valley of the Kings – KV 16 – 19th dynasty

Discovered on October 11, 1817, by Giovanni Battista Belzoni on behalf of Consul Henry Salt

At the beginning of October 1817, Giovanni Battista Belzoni, working on behalf of the British consul Henry Salt, commissioned a team of around twenty fellahs to carry out surveys in the Valley of the Kings. On October 11, while they were at work in the southeastern wadi, their research was crowned by an extraordinary discovery. Belzoni thus relates it in “Journey to Egypt and Nubia”: “Around midday, I was told that the entrance to the tomb discovered the day before had been widened enough for us to enter… I was the first to enter the opening, which had just been made to see if the way was passable. After having traversed a passage thirty-two feet long and eight wide, I descended a staircase of thirty-eight feet and arrived in a room quite large and decorated with beautiful paintings.

Discovered on October 11, 1817, by Giovanni Battista Belzoni on behalf of Consul Henry Salt

The key to reading the hieroglyphs was unknown; its “owner” – Ramesses I – would only be identified a few years later.

With an area of barely 148 m2, this tomb – referenced KV 16 – is one of the smallest in the necropolis. Its architectural plan is simple and rectilinear, with a stepped entrance followed by a sloping corridor that leads to a second staircase directly serving the burial chamber.

Discovered on October 11, 1817, by Giovanni Battista Belzoni on behalf of Consul Henry Salt

“It is clear that the plan owes much to the tomb of Horemheb (KV 57). This appears particularly in the decorative style, using blue-grey as a background for the scenes and texts. Some think that the same artists were at the origin of these two tombs,” specifies Kent Weeks.

The scenes for which “we have renounced all relief” (Erik Hornung) reveal a high pictorial quality and seduce with their chromatic richness of luminous harmony. The hieroglyphs are of extraordinary finesse, and the king’s cartouches are set against a white background. The lower part of the vignettes is, all around, bordered by two thick bands of colour: the first yellow bordered with black, the second red ocher. Then, the rest of the wall, down to the ground, is painted black. As for the upper part bordering the ceiling, which has not been painted, is composed of a frieze of Khekerous resting on a strip of alternating coloured rectangles.

Tomb of Ramesses I – Valley of the Kings KV 16 – 19th dynasty

discovered on October 11, 1817, by Giovanni Battista Belzoni on behalf of Consul Henry Salt

“The entrance to the sepulchral chamber is guarded by two figures of the goddess Maat, who welcome the deceased; the king is represented in the presence of the Memphite gods, Ptah and Nefertoum, and the deities of Abydos represented by the pillar-djed of ‘Osiris and the knot of lsis. On the side walls, several scenes from the Book of Doors evoke the Sun’s nocturnal journey. The back wall combines an Osirian scene on the right and a solar scene on the left. Far left, the king is shown in a position of jubilation, surrounded by the Souls of Pé and the Souls of Nekhen, the mythical ancestors of royalty.

Tomb of Ramesses I – Valley of the Kings KV 16 – 19th dynasty

Discovered on October 11, 1817, by Giovanni Battista Belzoni on behalf of Consul Henry Salt

The room has three small “annexe” rooms. The one dug into the southwest wall has a very beautiful scene representing Osiris standing between a divinity with the head of a ram and the serpent goddess Nesret, “the fiery breath” (it is, in fact, the Uræus ).

At the height, we note the presence of four small niches intended to accommodate the “magic bricks. “

Tomb of Ramesses I – Valley of the Kings KV 16 – 19th dynasty

Discovered on October 11, 1817, by Giovanni Battista Belzoni on behalf of Consul Henry Salt

Most of the room is occupied by an imposing red granite sarcophagus. Although damaged during looting, its domed lid is still there. “The sarcophagus was hastily finished, as evidenced by its decoration. Indeed, it is painted yellow, the texts and figures not having had time to be incised. In addition, the representations of the two goddesses, sisters and protectors of their dead brother Osiris are quite clumsily made. As is customary, Isis is at the foot, and Nephthys is at the head of the sarcophagus. The two goddesses stand on the hieroglyphic sign “Noub”, which represents gold”, explains Thierry Benderitter (osirisnet).

Tomb of Ramesses I – Valley of the Kings KV 16 – 19th dynasty

Discovered on October 11, 1817, by Giovanni Battista Belzoni on behalf of Consul Henry Salt

As Ali Reda Mohamed, the site inspector, told us, this tomb, which had been closed since 2008 for restoration by an Egyptian team, was reopened to the public on January 2, 2021.

Upon Khaled el-Enani’s inauguration, the Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities detailed the work carried out: “The floors we” e restored, and the walls were cleaned of bird and bat droppings… The existing inscriptions were also restored and cleaned, and the soot was removed… The sarcophagus also benefited from the care of the restorers, and the lighting system was improved”…

Tomb of Ramesses I – Valley of the Kings – KV 16 – 19th dynasty

discovered on October 11, 1817, by Giovanni Battista Belzoni on behalf of Consul Henry Salt

reopened to the public after restoration on January 2, 2021 – photo Ali Reda Mohamed

When Pa-Ramessou, a high dignitary and seasoned soldier, was chosen by Horemheb to succeed him, he was already around fifty years old. Around 1306-1307 BC, he became Pharaoh under Ramses I. Thus, this 19th dynasty, initiated by his predecessor, was marked by “the arrival to power of a family from the Delta (Ramses I, Séthy I)” and then marked “the transition to the Ramesside Empire”.

Pa-Ramessou is particularly known for two identical black granite statues representing him “as a scribe, ” discovered by Georges Legrain near the 10th pylon of Karnak on October 25, 1913 (Egyptian Museum in Cairo – JE 44863 – JE 44864).

discoveries near the 10th pylon of Karnak, October 25, 1913, by Georges Legrain

Egyptian Museum in Cairo – JE 44863

According to Manetho, his reign was short: 1 year and four months. This simple observation could explain the modest size of his tomb and its unfinished state.

If, in his account, Belzoni points out that the sarcophagus contained two mummies, these were not the remains of the sovereign…

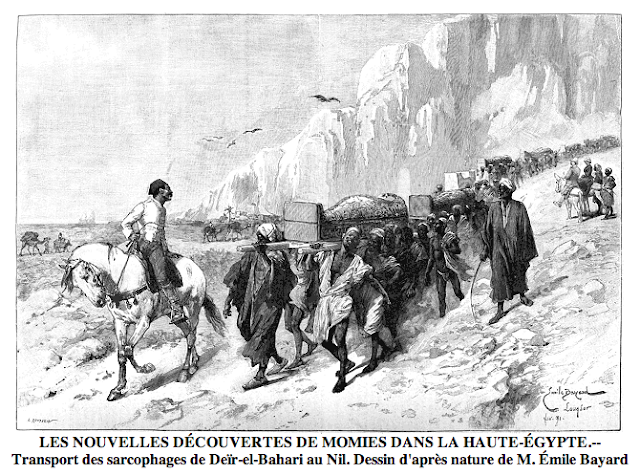

Indeed, after the looting that occurred in the necropolis, his mummy, like that of Ramses II, would first have passed through the tomb of Sethy I before joining the “hiding place of the royal mummies” (DB 320), where it was placed in the tomb and sheltered by the high priests of Amun during the 21st dynasty. This collective tomb was discovered in Deir el-Bahari by the Abd el-Rassoul family in 1871. The Antiquities Service only became aware of it in July 1881 and then transported all the mummies to the Boulaq Museum.

discovered in 1871 by the Abd el-Rassoul Brothers near Deir el-Bahari

In “The Find of Deir-el-Bahari”, Gaston Maspero thus evokes the successive “displacements” which are “recorded” on the coffins of the sovereigns before their final reburial in DB 320: “The three mummies of the 19th dynasty had a common destiny. The coffins of Seti I and Ramses II bear three identical inscriptions or almost, and which date back to three different periods; what remains of the coffin of Ramses I bears the remains of a hieratic text similar to the second inscription of the text of Seti I”.

What really happened to Ramses I’s mummy? How can we imagine that after these “post-mortem” wanderings, he has not yet found rest? How could it have been sold to an American, then passed through a museum in Ontario before being exhibited at the Michael Carlos Museum in Atlanta?

In 1909, in his “General Catalogue of Egyptian antiquities from the Cairo Museum – Coffins of Royal Hiding Places”, Georges Daressy thus presents, under the ref. CG 61018, the: “Fragment of coffin in the name of Ramses I. Sycamore wood – The original coffin of Ramses I having been destroyed, his mummy had been placed in another coffin of the XXIst dynasty; but this second coffin was it – even broken during the multiple transports of the royal mummies and only two fragments have come down to us: the lid and the head of the vat. The question then arises as to whether the mummy resting inside was indeed that of the sovereign?

On the other hand, in the 1900s, in order to overcome its financial problems, the Cairo Museum did not hesitate to get rid of a number of antiquities; it actually had its own auction room, but from there, it separated from a royal mummy…

The exact scenario still remains an enigma…

Still, in an article dated March 6, 2004, on the Atlanta mummy entitled “Rameses I Mummy Returned to Cairo”, the magazine “World Archeology” reports that: “After three years of intensive investigation into the royal mummy, including X-rays, CAT Scan, radiocarbon dating, computer imaging and other techniques, researchers are 95% certain that this is the mummy of Ramesses I. Arms crossed on the chest indicates that the mummy is indeed royal because this specific position was only reserved for royal characters”…

In 2003, through Zahi Hawass, it was finally returned to Egypt… Since March 9, 2004, it has been exhibited at the Louqsor Museum in the room dedicated to the glory of ancient Thebes… On its cartel, however, a doubt remains: “It is a royal mummy from the end of the 18th dynasty – beginning of the 19th. It may be that of Ramses I, founder of the 19th dynasty”…

in the hall to the glory of ancient Thebes

Sources:

Giovanni Battista Belzoni, Journey to Egypt and Nubia, Pygmalion, 1979

Kent Weeks, Illustrated Guide to Luxor, Tombs, Temples and Museums, White Star Publishers 2005

Kent Weeks, The Valley of the Kings, The Tombs and Funerary Temples of Western Thebes, Gründ, Paris, 2001.

Alberto Siliotti, The Valley of the Kings, guide to the best sites, Gründ, 1996

Nicholas Reeves, Richard H. Wilkinson, The Complete Valley of the Kings, Thames and Hudson, 1997

Claude Obsomer, Ramses II, Pygmalion, 2012

Pierre Tallet, Frédéric Payraudeau, Chloé Ragazzolli, Claire Somaglino, Pharaonic Egypt, history, society, culture, Armand Colin, 2019

Porter & Moss, Topographical Bibliography of Ancient Egyptian hieroglyphic texts, reliefs and paintings, Second Edition, Volume II, p. 534-535, Griffith Institute, Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, 1994

Theban mapping project https://thebanmappingproject.com/tombs/kv-16-rameses-i Ramses I – KV 16 – Thierry Benderitter, osirisnet.net https://www.osirisnet.net/tombes/pharaons/ramses1/ramses1_01.htm Georges Legrain, At the Harmhabi pylon in Karnak (Xth pylon), ASAE 14, 1914, p. 13-44 https://archive.org/details/annalesduservice14egypuoft/page/12/mode/2up Gaston Maspero, The Find of Deir-el-Bahari. Twenty photographs, by M. E. Brugsch, French printing house F. Mourès & Cie, Cairo, 1881 https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b8626666s/f1.item?fbclid=IwAR2kq2S6I6J4p5Sgs1J__8cR1XKUhIsnOFeTohkBxXme-lg1UEr9NZs4hSs#

Elisabeth David, Gaston Maspero, The Gentleman Egyptologist, Elisabeth David, Pygmalion, 1999

World Archeology, Rameses I Mummy Returned to Cairo, March 6, 2004, https://www.world-archaeology.com/world/africa/egypt/rameses-i-mummy-returned-to-cairo/ Luc Gabolde, Royal mummies in search of identity, Egypt, Africa & Orient, 2005 https://hal.science/hal-01895058/document

Cairo Museum No. 61001-61044, Coffins from the royal hiding places, Cairo Print. from the French Institute of Oriental Archaeology, 1909

https://archive.org/details/DaressyCercueils1909

Publié il y a 17th February 2021 par Marie Grillot

Libellés: Belzoni DB 320 JE 44863 KV 16 momie musée de l’Ontario Musée de Louqsor Pa-Ramessou Ramsès I Ramsès Ier Vallée des Rois

You must be logged in to post a comment.