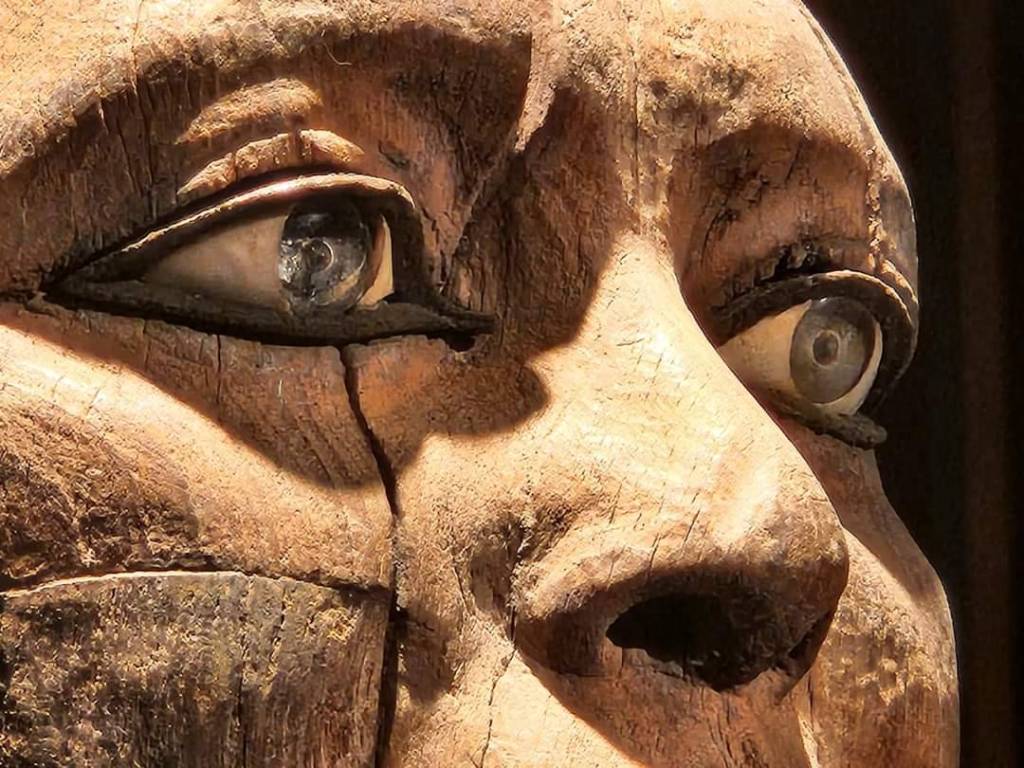

Today, I am sharing this invaluable fine art from ancient Egypt with you. Kaaper or Ka’aper (fl. c. 2500 BC), also commonly known as Sheikh el-Beled, was an ancient Egyptian scribe and priest who lived between the late 4th and early 5th Dynasties. Although his rank was not among the highest, he is well known for his famously exquisite wooden statue. A wooden statue of a woman, commonly considered to be Kaaper’sKa’aper wife, also came from the same mastaba (CG 33). Wiki.

Although the statue of that priest is famous enough, there is another tiny masterpiece: a statue of a woman, a noble lady, from the same mastaba. This is also a wooden statue, commonly considered to be Kaaper’s wife (CG 33).

Here is a report by the brilliant Marie Grillot about the delicate artistry of this statue. Enjoy reading, and Merry Christmas!

Ka-Aper’s wife: a noble lady of the Old Kingdom …

via égyptophile

discovered by Auguste Mariette in 1860 at Saqqara, in the Mastaba C8

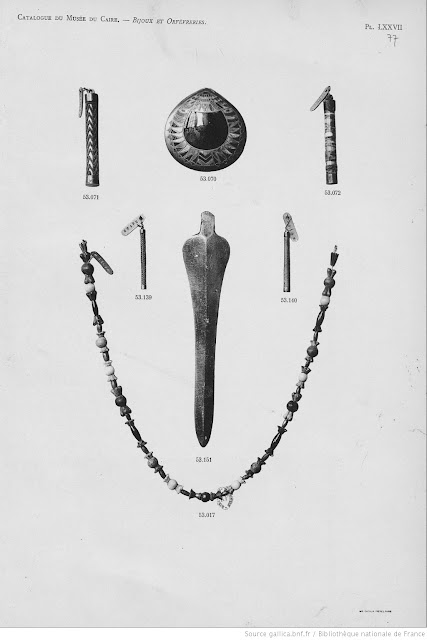

Egyptian Museum of Cairo CG 33 – photo of the museum

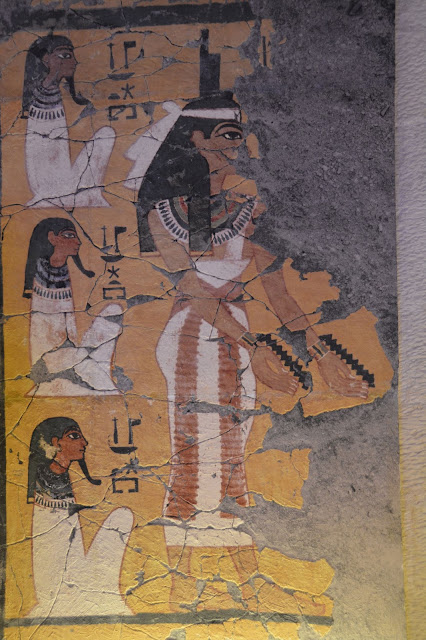

Wooden statuary was only beginning at the end of the 4th Dynasty, and this Statue is undoubtedly among the very first referenced female representations…

Carved in the round, dark brown wood, it was initially covered with a “fine patina of painted stucco”, which has now disappeared.

The face of the noble lady is rather round; her eyes are stretched, and her mouth is closed.

She wears a mid-length hairstyle covering her ears. As Mohamed Saleh and Hourig Sourouzian explain in their “Official Catalogue of the Egyptian Museum in Cairo”, it is “streaked with locks that end in small curls, and divided by a middle parting”. They also specify that “this wig is commonly found in female representations of the Old Kingdom”.

discovered by Auguste Mariette in 1860 at Saqqara, in the Mastaba C8

Egyptian Museum of Cairo CG 33 – photo of the museum

Her neck is adorned with a wide necklace of the usekh type, with some traces of colour remaining. The torso, with its marked chest, is thin and straight. Amputated by the upper limbs, it stops at the base of the shoulders. The statues were, in fact, made in several parts, and, in this case, the arms were added and attached to the bust using tenons. We can observe this “assembly” on multiple examples of wooden statuary…

The legs are also missing, but her attitude shows that she was depicted standing.

She is wearing a long, tight dress held up by two wide, sculpted straps “slightly projecting”.

The wood, with its visible veins, has worked and cracked over the course of more than 4,500 years. In particular, we notice an apparent crack that goes down from the neck to the navel and two more discreet ones, starting from the top of the skull towards the chin and the other from the left eye towards the chin. At the level of the right groin, we also note a considerable lack of triangular shape.

Despite these injuries, this lady retained the nobility and dignity pertaining to her rank, and the sculptor took care to render and respect her.

discovered in 1860 by Auguste Mariette at Saqqara in Mastaba C8

Egyptian Museum of Cairo – CG 34 and CG 33

In the “Guide du visiter au musée de Boulaq” (1883), Gaston Maspero describes it as number 1044: “Statue of a woman of which only the head and the torso remain. It was discovered in the same tomb as the Statue of Sheikh el-beled and is said to represent this character’s wife. In any case, it was wonderful and could be compared with Sheikh el-beled if it were not unfortunately so mutilated.”

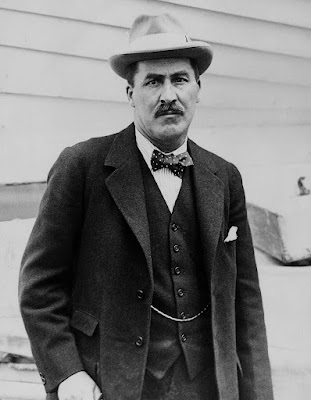

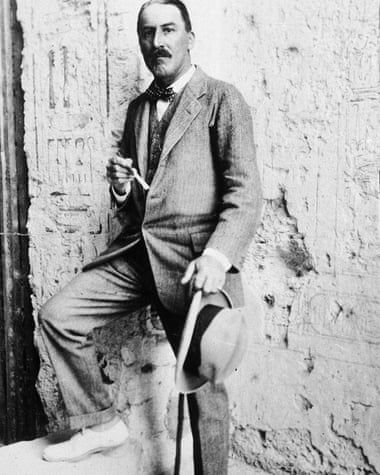

Auguste Mariette, then the director of Egyptian antiquities, discovered the two statues in Saqqara in 1860.

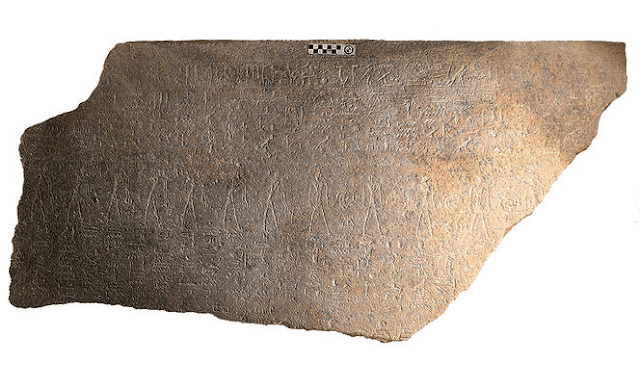

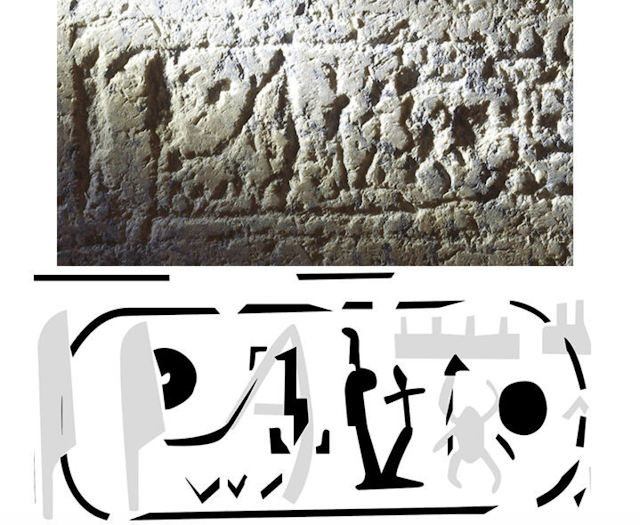

concerning the discovery of the wooden statues of Ka-âper (Kaaper) – Sheikh el-beled – and his wife

discovered by Auguste Mariette in 1860 at Saqqara, in the Mastaba C8 Egyptian Museum of Cairo CG 34 and CG 33

In the book Les Mastabas de l’ancien Empire, published in 1889 and co-signed with Gaston Mapero, he presents the site and details the circumstances of the discovery.

“The oldest, the most extensive, the most important of the necropolises of Memphis is the one to which the village of Saqqara gave its name. The necropolis of Saqqara is located in the middle of the sand, just at the point where the desert begins and where the cultivated land ends; it is a sandy plateau which dominates by about forty meters the green plain extended at its feet. At the top of the plain, we find the necropolis…” He will uncover a huge number of tombs and mastabas there.

concerning the discovery of the wooden statues of Ka-âper (Kaaper) – Sheikh el-beled – and his wife

discovered by Auguste Mariette in 1860 at Saqqara, in the Mastaba C8 Egyptian Museum of Cairo CG 34 and CG 33

Among these latter is the one that will be referenced, C 8 (the letter C corresponds to those of the second half of the 5th dynasty), discovered near the pyramid of Userkaf.

It will turn out to belong, according to Mariette’s transcription, to Khou-hotep-her (Ka-âper – Kaaper), a high official, chief priest. He was responsible for reciting prayers for the deceased in the temples and mortuary chapels where he officiated during the 5th dynasty (2465 -2458 BC).

“It was at the bottom of niche B, belonging to the small room, that the precious wooden statue was found… The head, the torso, and even the stick were intact, but the legs and the base were irremediably rotten, and the statue was only standing because of the sand which pressed on it from all sides. At the door C. of the small room, in the sand, and overturned in the place where it had obviously been thrown, was the other wooden statue,” he relates.

discovered by Auguste Mariette in 1860 at Saqqara, in the Mastaba C8

Egyptian Museum of Cairo CG 34

The statue of Ka-âper is so realistic that, upon discovery, the workers struck by its resemblance to the “chief of their village” gave it the name “Sheik el-beled”. It is undoubtedly one of the most emblematic statues of the Fifth Dynasty… That of his wife, because of her “amputations”, will remain more “confidential” and will not know the notoriety of her famous spouse…

It is exhibited at the Egyptian Museum in Cairo, Tahrir Square, under reference CG 33.

Sources:

Gaston Maspero, Visitor’s Guide to the Boulaq Museum, 1883 edition, Typ. Adolphe Holzhausen, Vienna, 1883 https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k6305105w.texteImage Auguste Mariette, Gaston Maspero, The Mastabas of the ancient empire, Paris, 1889 http://digi.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/diglit/mariette1889/0033?sid=02fcf46a77d8eaf4a9cd67e6974f1cc1 Ludwig Borchardt, General catalogue of Egyptian antiquities from the Cairo Museum – Statuen und Statuetten von Königen und Privatleuten im Museum von Kairo, Nr. 1-1294, Berlin Reichsdruckerei, 1911 https://archive.org/details/statuenundstatue53borc Gaston Maspero, Essays on Egyptian Art, E. Guilmoto Editeur, Paris, 1912? https://archive.org/details/essaissurlartg00maspuoft https://archive.org/stream/essaissurlartg00maspuoft/essaissurlartg00maspuoft_djvu.txt Gaston Maspero, Ancient History of the Peoples of the Classical Orient. I, Librairie Hachette et Cie, Paris, 1895-1899 http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k6134639f/f8.item.r=beled.langFR Elisabeth David, Mariette Pacha 1821-1881, Pygmalion, 1994

Mohamed Saleh, Hourig Sourouzian, Official Catalogue of the Egyptian Museum in Cairo, Verlag Philippe von Zabern, 1997

You must be logged in to post a comment.